Issue 19: American S-Bahn

Plus: How to redraw cities with tangled property rights, the secret history of inflation targeting, and the end of lead pollution in the developing world

Works in Progress Issue 19 is out today.

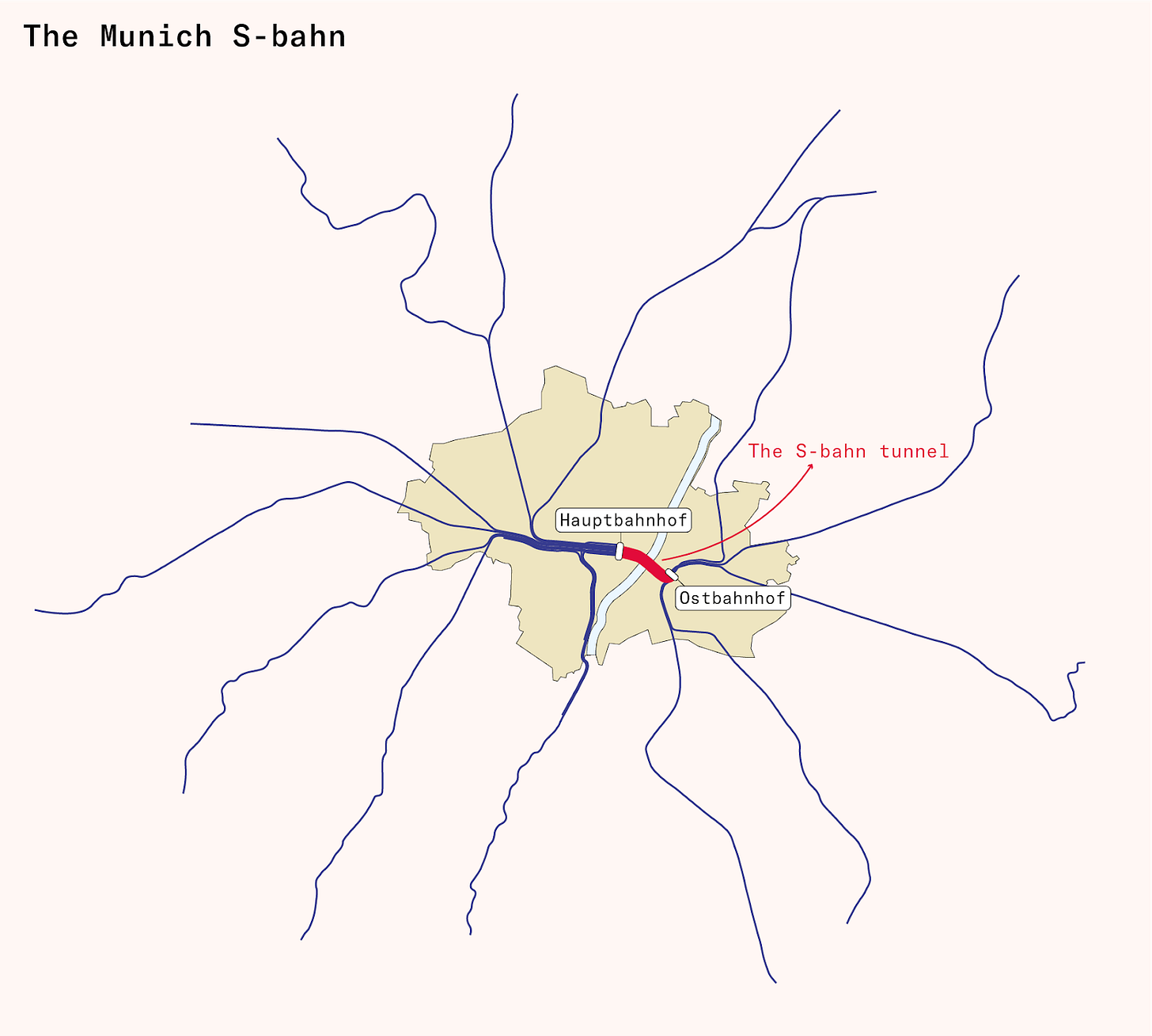

Our spotlight piece explains how cities can create commuter metro systems hundreds of miles long for the price of a few miles of new tunnel, as with S-Bahn, Crossrail or RER systems.

We also have pieces on:

Why bad science is the ultimate cause of today’s eye-wateringly expensive nuclear power plants;

Why lead poisoning is actually one of the easiest global health issues to solve;

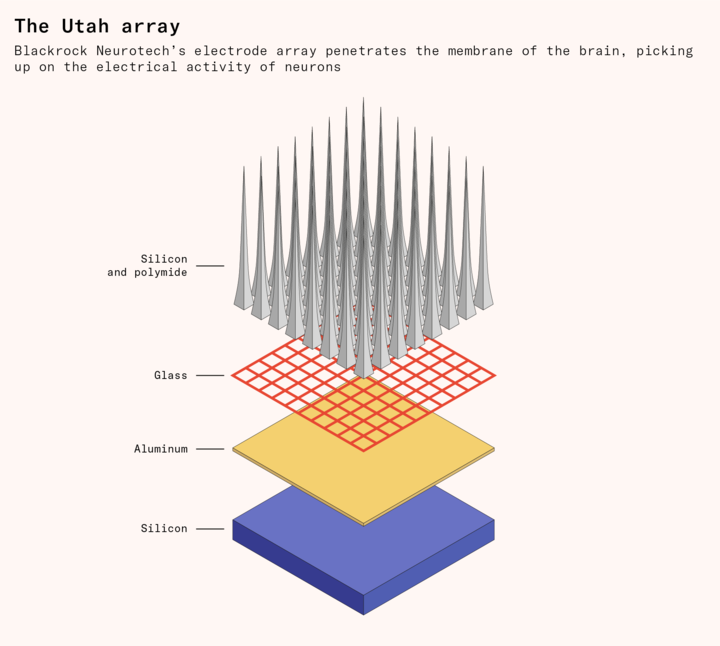

The brain-computer interfaces like Neuralink set to change the world;

And the urban planning trick – land readjustment – that allows Japan to build such efficient cities.

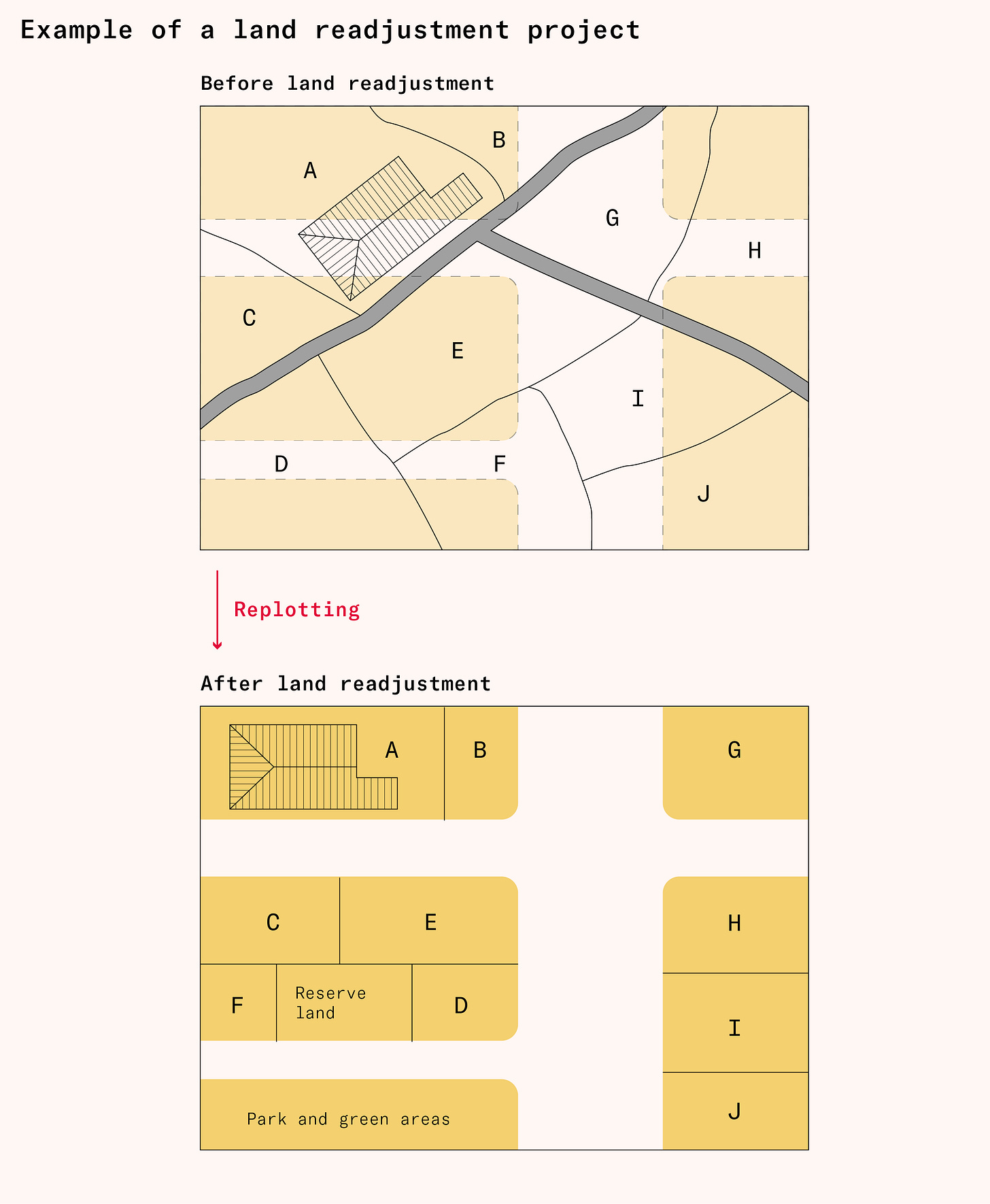

Japan went from having few roads designed for wheeled vehicles to the world's most advanced urban infrastructure. The secret, writes Anya Martin, is land readjustment, a system where neighbors pool their plots, redraw boundaries to create space for roads and parks, then redistribute smaller but more valuable parcels of land. Each owner loses some land but gains from the collective uplift that new infrastructure brings. First used after the 1923 earthquake, land readjustment has now been used to create 30 percent of Japanese urban land, including many of its train stations and urban roads. Land readjustment is known as ‘the mother of urban planning’ in Japan, and it might be the key to building infrastructure in cities in the Western world too.

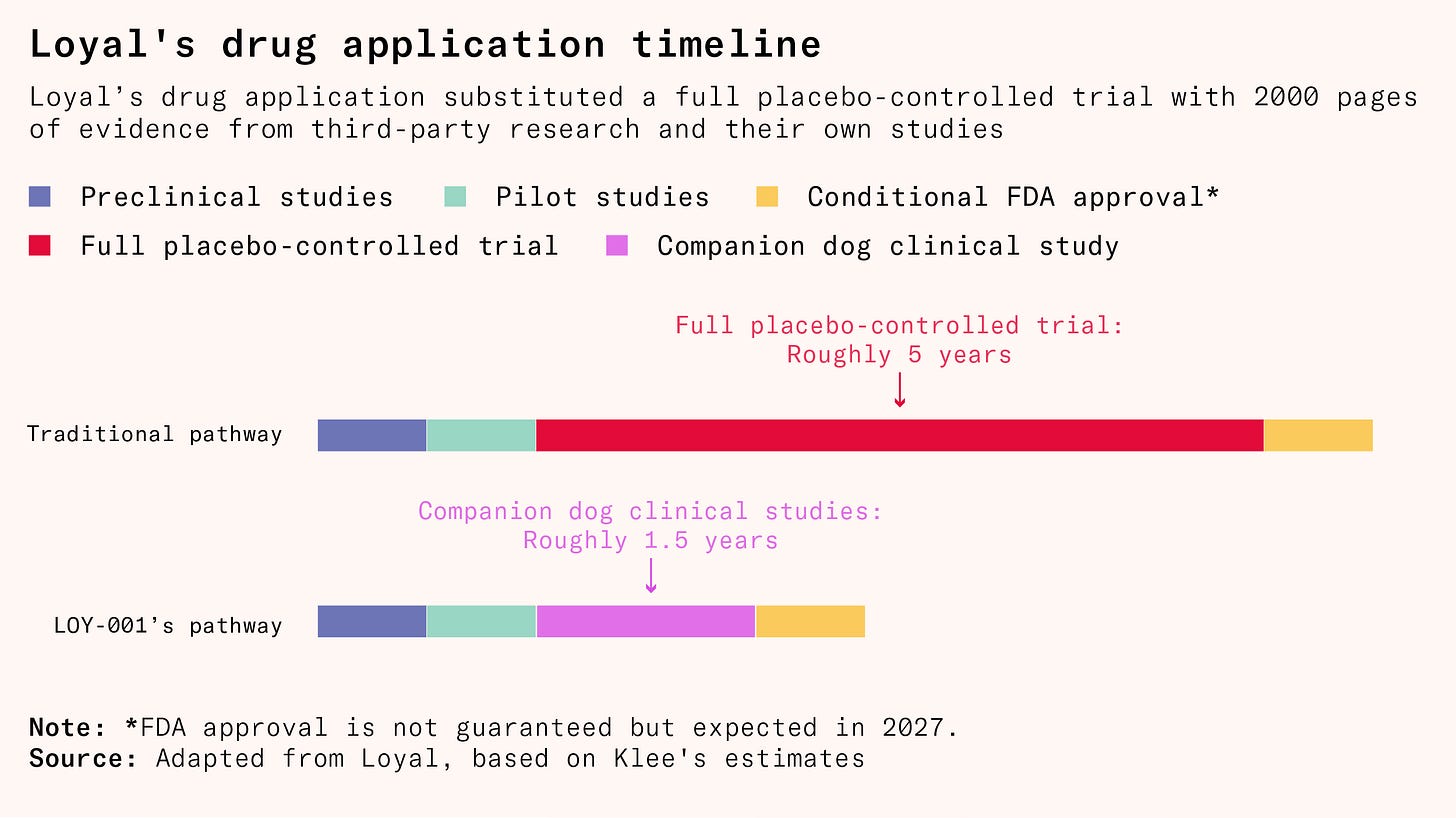

Animal drugs are approved by the same FDA that governs human drugs. A 2018 rule change created a shortcut that has reshaped animal drug discovery, writes Trevor Klee. The expanded MUMS (Minor Use and Minor Species) Act allows companies to sell drugs for major animal diseases based on proof of safety and a ‘reasonable expectation of effectiveness’ rather than full efficacy trials, which can add years and millions of dollars to getting a drug to market: Loyal's dog longevity drug got approved with $1 million in studies rather than a $20 million efficacy trial. If this regulatory tweak manages to unleash a lot of new drugs for animals that end up working, it may show us how to reform how the FDA reviews human drugs as well.

Inflation targeting – now the standard way of controlling inflation and the overall macroeconomy across the developed world – was not initially based on academic consensus. Instead, it was improvised by a New Zealand politician, explains Oscar Sykes. Facing 17 percent inflation, Finance Minister Roger Douglas surprised his own advisers by announcing on TV that he'd reduce it to ‘0 or 0 to 1 percent’, and require the New Zealand central bank to do what it took to get there. This became law, and the central bank governor would negotiate targets and face dismissal for failing. Other central bankers thought the idea was crazy, but within a decade, most developed countries had adopted it.

Brain-computer interfaces will receive FDA approval within five years, writes Rebecca Hiscott. After decades of trials the technology now works. Today, they help people with spinal injuries, ALS, and stroke regain function in a way no drugs currently can. Neuralink allows 29-year-old quadriplegic Noland Arbaugh to write e-mails, play Mario Kart and browse the web from bed after just months of home training. Casey Harrell, rendered mute by ALS, can speak to his daughter after only two short calibration sessions, thanks to a large-language-model decoder that maps neural signals to sounds in real time.

Nuclear power is unaffordable because of ALARA, a rule that means radiation exposure must be 'as low as reasonably achievable’, writes Alex Chalmers. ALARA exists because regulators believe in the Linear No Threshold: the theory that any radiation causes cumulative harm, with no safe level and no bodily repair. However, modern science shows LNT is wrong: DNA repairs itself and damage is non-linear. It is time to abandon ALARA and make nuclear power affordable again.

Lead has poisoned humanity for eight thousand years, write Clare Donaldson, Lauren Gilbert, and James Hu. Though rich countries eliminated most lead exposure, one in three children worldwide still has dangerously high levels of lead in their blood. Lead damages brains and cardiovascular systems, costing the global economy one trillion dollars annually and killing 5.5 million people each year – more than unsafe water and poor sanitation combined. But the solutions to it are surprisingly simple, and may not take much effort to bring into effect. The same choices that cleaned rich countries – test, identify sources, regulate, and help manufacturers switch – can eliminate lead everywhere.

Europe and America’s nineteenth century railway networks usually terminated at city edges rather than connecting with each other in the city centres. Many cities have converged on a solution, writes Benedict Springbett: drilling a short central tunnel to link suburban lines on opposite sides of the city. A 4.3-kilometer tunnel allowed Munich to create a network carrying more passengers than some systems four times its size; London's Elizabeth Line used 21 kilometers of tunnel to build a line 117 kilometers long. Cities like Boston and Manchester already have 90-95 percent of their potential metro networks built as legacy lines, needing only small connecting tunnels. Where Chinese cities must build entire metro systems from scratch, cities with nineteenth-century railways can deliver results just as good by filling in the missing ten percent.

Podcasts in Progress

We have launched a podcast feed. Subscribing to this will get you all the podcasts we produce. So far, we have two series in the works.

Hard Drugs, by Saloni Dattani and Jacob Trefethen, is about medical innovation and global health. Episode one, out this week, is about the history of the fight against HIV all the way up to the new drug Lenacapavir, which blocks infections from HIV by nearly 100 percent. You can subscribe on any major podcast platform.

We are also producing conversations about the same topics that we like to write about: cities, science, energy, coffee, and more. In two weeks, we will release a conversation about what we call ‘the great downzoning’ – the period in which cities around the world started to ban the densification of residential neighbourhoods – and try to understand why this happened. Let us know in the comments who you’d like to hear us speak with in future episodes.

More from Works in Progress

Peter Brookes makes the case for front-loaded child benefits.

Jason Hausenloy, Elaine Perlman, and Duncan McClements discuss the importance of the The End Kidney Deaths Act.

Rodolfo Rosini explains the quest to create a nearly-zero-energy computer chip.

Seán O'Neill McPartlin writes about NIMBYism and how to resolve it.

Yassine Meskhout extolls the wonders of modern drywall.

Evan Deturk on the 80,000-year history of the tomato.

Benedict Springbett explains how to upzone Hong Kong.

Alex Chalmers on the collapse of the Spanish electricity grid, how Britain broke its own grid, the world's first electric grid, and how nuclear reactors work.

Alex also tells the story of how Airbus took off – a truly European world-beater, and one of the most successful examples of industrial policy in recent history.

Samuel Hughes writes about the merits of unified land ownership and London’s slowly improving mid-rise architecture.

We published Links in Progress posts on everything from our reading habits in March, April and May, beautiful buildings being built today, what’s new in biology, legalizing the condo, and good drug news. We also published a nuclear power syllabus.

What we’ve been up to

Sam spoke at Blackbird’s Sunrise Festival in Sydney about ‘the elements of progress’ – why things like cities, energy costs, and unconventional scientific research matter so much for human progress. He also spoke at the Friedrich Naumann Foundation in Germany, and appeared on the podcast of the Institute of Economic Affairs and on Tech Today.

Other than achieving a handstand for the first time, taking his children to Center Parcs, Cornwall, and Mallorca, and an awful lot of article editing, Ben has done very little this quarter.

Saloni wrote about the decline in cancer mortality and how it hasn’t just been about the decline in smoking; about the massive improvements in survival for childhood leukemia; and about the lifesaving value of measles vaccination.

Rachel manned the Stripe Press bookshop at Stripe Tour London. She also went on safari in Botswana and Zambia and saw many, many animals, and wrote about Simone de Beauvoir.

Pieter has been trying to find Europe’s YIMBYs. He also went to some new states, started a Qing book club, and did lots of editing.

Aria visited Singapore as part of the Civic Future Fellowship; Portugal to eat as many eggs and egg byproducts as possible; and The Adam Smith Institute to talk about liberal pronatalism.

Alongside maximizing his background radiation exposure, Alex has been touring the Middle East and engaging in a public war of words with the UK’s national AI institute.

Samuel wrote about why Georgian developers laid out parks, the fall and rise of London commercial architecture, and recent misadventures of English housing reform. He is currently in Germany, learning about the successes and failures of German urban policy.

Atalanta has a painting of the ASMR-turned-Onlyfans-turned-tradwife Gwen the Milkmaid in the exhibition Lady Lillith at Alice Black gallery in London. The opening party (all welcome) is tonight. She has also been painting historically accurate rouge on a Greco-Roman plaster cast.

(Some info about who we all are is here.)

Happy reading!

– The Works in Progress team

Why does the graph of New Zealand inflation apparently resemble one that would chart a barrel of Crude? After all, New Zealand has so manu independent sources of energy. Just a coincidence I guess.

It's a pity that you skipped so blithely over the history of inflation targeting without overtly noting the negative consequences of how arbitrarily it was chosen, without any consideration of other crucial issues such as economic growth and employment. Inflation is important, but that concern must be balanced against other important concerns.