Why child benefits should be front loaded

The timing of benefits matters to families, and doesn't change costs for governments

We’re hosting a Stripe Press pop-up coffee shop and bookstore on Saturday, June 28, in Washington, DC. RSVP here if you can make it.

The developed world faces below replacement fertility that is driven by people having fewer children than they would like to have. This has serious social and economic ramifications: it creates aging populations with fewer workers for every dependent and fewer innovators. Already, the aging population accounts for a third of the output gap from pre-2008 trends in the US. Contrary to popular perception, having children does not destroy the environment. And, perhaps most importantly, people are having fewer children than they say their ideal is – a striking gap.

As such, there is growing interest in what policies could support people in their family formation aspirations, including financial measures which can affect how much people on the margin feel sufficiently supported to take the jump to create families.

The United Kingdom, along with a number of other countries with low fertility like Italy and Japan, is under fiscal strain. This make it a tough political sell to spend more public money to support people in having families.

Fortunately, there is a list of zero-cost, politically feasible policies to support family formation. At the top of the list was taking the amount we currently spend on child benefit, and front loading it, so families can get the entire net present value in one go, if they wish.

Front loading child benefit would be popular, it would support families and family formation (to the betterment of our long run economic growth outlook) and it would come at zero or minimal fiscal cost (depending on implementation). The government could expedite its implementation tomorrow by lending its support for an existing bill.

It might seem like merely changing the timing of a benefit rather than its amount, would have no impact. But it can make an enormous difference as it provides a way of maintaining living standards at a time when they would otherwise take a dip.

The direct monetary cost of raising a child is at its highest when a child is young. The Child Poverty Action Group estimated in 2022 that the cost of raising a one year old is £273 a week, falling to £73 a week by age 16. When a child is born, they are expensive. They require their own equipment: cots and push chairs and the like. They require extensive care that is usually delivered at a mix of financial cost (in the case of paid childcare) and opportunity cost (in the case of care done by the parents). As children get older, they increasingly look after themselves (or at least the care they require becomes less intensive). This means that a front-loaded child benefit meets financial need where it is greatest. (This also means that it could be an efficient way to reduce child poverty, fulfilling the original motivation for child benefit.)

The Child Poverty Action Group’s figure is also a large underestimate of the full change in financial burden as a child grows older, because it does not consider the other tradeoffs that new parents undergo. Many parents work less during their children's early years which is an additional burden on parents’ finances. As a child grows older, it becomes easier for parent and child alike to juggle work with family.

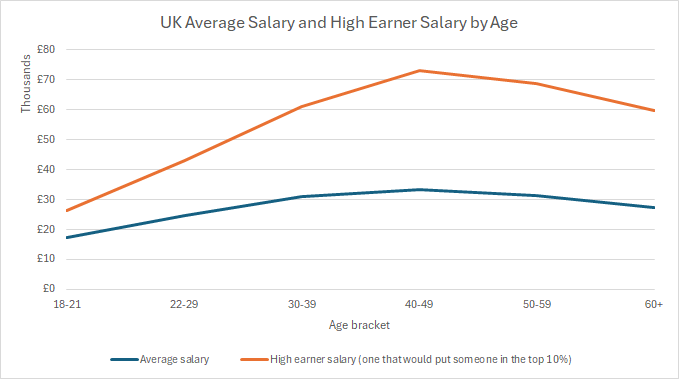

Average earnings increase continuously from 18 to 50. In 2022, the average age of becoming a mother was 30.9 years (33.7 for becoming a father) in England and Wales. Given earnings trajectories and age of parenthood, parents are typically earning less when their children are young than they will when their children are older. A front-loaded child benefit would supplement parental income when it is at its lowest.

There is also the discount rate to be mindful of; people decrease the value of a given amount of money in the future by as much as 6.5 percent per additional year of waiting – perhaps more for a government benefit that is insecure. The evidence suggests that this discounting mutes the incentive effects that otherwise exist for ongoing benefits.

Studies looking at ongoing payments show they can have a modest increase in births. One study looking at Western Europe found, on average, there was a moderate boost to birthrates from benefits distributed across the duration of childhood. A rough calculation of OECD figures found that support of 87 percent of GDP per capita, distributed over sixteen years (similar to the over £20,000 of the UK's child benefits for eldest children), only boosts births by 3 percent. Third child births are generally known to be sensitive to financial support, yet the withdrawal of child benefit for third-borns precipitated a four percent fall in third births – noticeable, but not game-changing.

Lump payment benefits, concentrated in the early years, are different. One study of Spanish lump sum payments finds much larger effects. The first investigation looked at birth rates in Quebec following the introduction of large, lump-sum baby bonuses. According to the study, every one percent of GDP per capita offered to parents and prospective parents raised births by 0.25 percent. This implies effects at least three times more powerful than ongoing payments, and perhaps as much as eight times larger.

In 2022, Lord Farmer suggested a British bill to allow parents to bring forward future child benefit payments, such that the overall amount of child benefit would be the same. It remains in committee stage, a fate common for bills introduced by parliamentarians without government endorsement. If it wished to easily and cheaply support young families, the British Government could extend its support to Lord Farmer’s bill, increasing the speed through which the bill would likely pass through parliament and its chances of succeeding.

Peter Brookes is the director of the Centre for Family and Education.

There are probably a number of ways to slice the cost of children. One is material costs of attending to their needs, in which Jon Neale above is correct to observe older children cost more. One is costs of providing care, which is much higher for younger children. Another is the life course income effect - parents will earn more as their children age, enabling them to meet the needs of older children more effectively, but forgoing income when children are very young.

Then there's the upfront cost in terms of pram, cot, baby car seat etc for the first child with lower costs for the second child. But then costs probably pick up again for third and subsequent children as third children would require a larger car (depending on age gaps and car seat laws of course) and an additional bedroom.

All of this is a long-winded way of saying there's no clear 'right' way to think about it, but front loading should at least be a consideration.

Love this idea! What’s being done to lobby for it?

Are the Quebecois and Spanish examples similar front loading of benefits, or an additional lump sum?

I guess one thing that might make it unpalatable is that the government who introduce it will bear the cost of the lump sum without getting most of the benefit of the decreased regular payments.