How Airbus took off

Why you can build a European airliner, but not a European Google

We recently released Issue 18 of Works in Progress. Read about the rise and fall of the Hanseatic League, the prehistoric psychopath, and steam networks here.

Alex is an editor at Works in Progress, focused on AI and energy. He’s also the author of Chalmermagne, a Substack covering technology, policy, and finance.

Would you rather fly in an Airbus or a Boeing? It seems like an easy question.

As Alaska Airlines Flight 1282 flight climbed to 16,000 feet on a January evening in 2024, passengers were stunned when a hole was blasted in the side of the plane. They were hit by howling winds as tray tables were ripped from the backs of seats. Were it not for their seatbelts, they would likely have been sucked out of the plane. It later transpired that the plug which sealed the exit door was missing four critical bolts that held it in place.

The Alaska Airlines incident fortunately didn’t result in any fatalities. Not everyone who has flown on a Boeing 737 MAX in the last few years has been so lucky.

2018 and 2019 saw two 737 crashes that killed 346 people after the plane’s Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System, a feature that pushes the plane's nose down to prevent stalling, triggered repeatedly due to a faulty sensor. It later transpired that Boeing had not adequately disclosed how the system worked in training manuals.

While Boeing wrestles with lawsuits and regulatory investigations, its rival Airbus has stayed out of the headlines – a happier place for the manufacturer of commercial airliners.

Europe is a graveyard of failed national champions. They span from the glamorous Concorde to obscure ventures like pan-European computer consortium Unidata or notorious Franco-German search engine Quaero.

Airbus is the rare success story. European governments pooled resources and subsidised their champion aggressively to face down a titan of American capitalism in a strategically vital sector. Why did Airbus succeed when so many similar initiatives crashed and burned?

Airbus prevailed because it was the least European version of a European industrial strategy project ever. It put its customer first, was uninterested in being seen as European, had leadership willing to risk political blowback in the pursuit of a good product, and operated in a unique industry.

An industry on the brink

In the early days of commercial aviation, US aerospace companies dominated the market for passenger jets.

The Buy America Act of 1933 forced the US government to buy from American producers where possible. Military orders super-charged the industry and brought significant knowledge spillovers.

The Boeing B-47 bomber, introduced in the late 1940s, pioneered the use of 35-degree swept wings (i.e. wings that point backwards at an angle of 35 degrees, rather than going straight out perpendicularly), which reduce drag at high speeds. This design went on to inspire nearly every commercial airliner around the world.

Meanwhile the Boeing 707, the company’s first ever airliner, shared a fuselage with the KC-135 Stratotanker, its military refueling aircraft.

In the face of the US, European aerospace companies cut a sorry figure. The British Aircraft Corporation, Sud Aviation in France, and Messerschmitt-Bölkow-Blohm (MBB) in West Germany were all left to compete for orders in a fragmented continental market, with little R&D or marketing heft. Meanwhile, European airliners who bought American planes could apply for discounted loans from EXIM, the US’s credit export agency.

Between 1960 and 1967, British and French manufacturers saw a 50 percent decline in aircraft deliveries. In 1966, the UK government had even contemplated forcibly merging and nationalising much of the country’s industry.

European governments had poured money into their national champions in the belief that the maintenance of a civilian aerospace industry was critical for sovereignty, but it was unclear if these companies would survive the decade.

Amid this gloomy backdrop, European governments concluded that their industry’s future depended on cooperation.

The UK and France agreed to pool the resources behind Concorde in 1962 to fight what Charles De Gaulle called ‘the American colonisation of the skies’, but the Germans declined to participate due to their (well-founded) scepticism about the project’s economics. This didn’t stop the Germans teaming up with the Dutch on the long-forgotten VFW-Fokker 614. This short-haul jet struggled to find customers at a time when airlines preferred to use cheap prop aircraft for regional city-hopping, dooming the project to collapse once state aid was withdrawn in 1977.

In 1965, the French, British, and German governments launched a working group to evaluate the potential of a wide-body commercial aircraft, which would later become the A300. Two years later, the three governments agreed to bear the entire costs of the development of the ‘European Airbus’. In 1970, the coalition was formalised with the creation of Airbus Industrie. The consortium quickly expanded to include Spain and the Netherlands.

The making of a world leader

So how did this unlikely band of brothers go on to build a global leader, rather than another Econ101 case study about the perils of industrial policy?

The single biggest factor was a focus on the customer.

Unlike many future industrial strategy projects, which would focus on creating European-owned capabilities for their own sake, the Airbus team were seized by the need to build a jet that airliners would want to buy. They didn’t have much choice: if they failed, there was a reasonable chance the consortium’s domestic aerospace suppliers would collapse.

They were helped enormously in this by their setup. While Airbus didn’t become a unified corporate entity until 2001, the partnership had a strong central leadership from the beginning. Unlike other industrial consortia, which tended to be leaderless venues for intra-European turf wars, Airbus united marketing, procurement, and design.

Roger Béteille, who led the A300 programme, probably bears more responsibility for Airbus’s early success than anyone else. Béteille wasn’t interested in building an inferior European Boeing copy. Instead, he invested significant time in getting to know his potential customers and what they needed. This led to Airbus quickly tossing the original design for a 300-seat A300, in favour of a 225-250 seater, when it became clear that Air France and Lufthansa wanted a smaller product.

The revised A300B would prove much cheaper to develop, in part because it allowed the consortium to dispense with the expensive Rolls Royce engine in favour of a cheaper American alternative. In response, the UK exited the project, only to later return with a lower ownership stake.

This willingness to risk political blowback and avoid petty chauvinism in equipment choice was rare in industrial strategy.

Béteille went one step further. He designated English the official language of the project, instead of the usual mixture of languages that characterised European projects, and forbade the use of metric measurements to make it easier to sell into the US market.

Along with Felix Kracht, Airbus’s first production director, Béteille set a division of labour between the different countries that has persisted, with minor adjustments. French firms handled the cockpit, control systems, and lower-center fuselage; Hawker Siddeley (the inventor of the Harrier jump jet) in the UK designed and built the wings; German companies produced various fuselage sections; the Netherlands managed moving wing components; and Spain was responsible for the horizontal tailplane.

Based on Béteille’s market research, the A300B was optimised for fuel efficiency. The team stripped out unnecessary weight by using composite materials and raised the cabin floor to add cargo space. Hawker Siddeley’s wings, which would go on to influence industry standards, were designed with a curved shape on top to reduce air resistance, allowing greater lift and fuel efficiency.

At a time when almost every commercial jet had three or four engines, Airbus opted for a twin-engine design. The plane could theoretically fly on one and the company concluded that only a single extra engine was needed to provide redundancy for safety. The much cheaper twin-engine design is now the industry standard, even for ultra long-haul flights.

Despite the technical ingenuity behind the A300B, early business was slow. By the time the aircraft entered service in 1974, it had struggled to attract commercial interest beyond state-owned flag carriers like Air France, which had placed the first A300B order in 1971 for six jets. Even these airlines continued to operate Boeing-dominated fleets.

One problem was unfortunate timing: the oil shock of 1973 had caused operating costs to spiral for airliners, so there was little appetite for experimentation in the air.

There was also residual suspicion of European industry among US airliners. Sud Aviation’s Caravelle had been used by some American airliners, but the company was notorious for its sloppy after sales maintenance and service. There had also been an ugly dispute over landing rights for Concorde, with the US heavily restricting the aircraft’s operation out of noise concerns. The French suspected more sinister commercial motivations were at work. Jacques Chirac, then French Prime Minister, raised the temperature, declaring that: ‘The Airbus consortium will not be daunted by the Americans who killed off the Concorde. ... We will fight any trade war blow-by-blow as the future of the aeronautical industry and their employees is at stake.’

Against this backdrop, Airbus did everything it could to de-emphasise its European heritage as it toured the US. It refused to involve the French or German embassies in its sales efforts, much to their irritation. Airbus representatives drove home how a third of the plane’s value derived from US-made components, more than any single European partner nation’s contribution. They also mastered the world of DC lobbying, successfully outmaneuvering Boeing and Lockheed’s attempts to use anti-trust regulations to shut the European entrant out of the US market.

Sustained by early European market commitments and early sales in Asia, Airbus was eventually able to clinch its first US order in 1977. Eastern Airlines (EAL), which had been impressed by the A300B’s fuel economy and low noise levels, agreed to the trial lease of four aircraft and three spare engines for … one dollar. These terms would have been unconscionable for a normal private company, but they were transformative for state-backed Airbus’s fortunes. Frank Borman, conservative Republican, former NASA astronaut, and EAL’s CEO emerged as a public champion of the A300B as an ‘American aircraft’.

The A320

Béteille and Kracht weren’t content with building one aircraft. From the beginning, Airbus had targeted a 30 percent global market share. This meant building more than wide-body aircraft like the A300B.

The A320, which entered operation in 1988 was a narrow-bodied aircraft that could carry 150-180 passengers. It was optimised to fly short- and medium-haul routes economically, and a masterclass in engineering and timing.

By the 1980s, airliners were looking to replace their ageing narrow-bodied fleets, with the Boeing 272 and McDonnell Douglas DC-9 having been in operation for more than two decades.

The A320 was the first commercial aircraft to implement full digital fly-by-wire controls. Before the A320, the pilot’s controls pulled physical cables attached to the flaps, rudder, and other control surfaces on the plane. Fly-by-wire meant that controls sent electric signals to the plane’s computers, which then commanded motors to move the control surfaces. This made life easier for the pilots by reducing the need for constant manual adjustment and stripped out heavy components that needed maintenance.

The A320 was also the first commercial aircraft to introduce envelope protection, a system that automatically prevents dangerous actions, such as tilting too steeply, flying too slowly, or making maneuvers that could overstress the aircraft structure.

Again, the A320 wasn’t an overnight success, with new technology and existing relations with Boeing slowing uptake. Airbus again relied on British and French orders to gain market credibility. But by the early 1990s, its superior technology combined with Airbus’s willingness to flex the design, with the A319 (smaller) and A321 (larger) allowing airliners to operate mixed fleets with common cockpits, began to win fans. The A320 is now the most popular airliner family in history and remains in widespread use today.

The success of the A320 led Airbus to profitability in the mid-1990s. By 2019, Airbus had displaced Boeing as the largest aerospace company by revenue.

Why Airbus’s success is so hard to repeat

If Airbus proves industrial strategy can work, why haven’t other European ventures fared better?

Good industrial strategy requires favourable market conditions, consistent strategy in the face of political headwinds, and the courage to call it a day if failure seems likely. Getting one of these right is tough, and all three is exceptionally rare.

Concorde was a marvel of engineering, but even without US obstructionism, it had little prospect of commercial viability. In today’s money, it cost £16 billion to develop, roughly ten times the cost of the Boeing 727, making it the most expensive plane of its age by some margin. Its limited passenger capacity, fuel inefficiency, and expensive maintenance meant that a ticket for a round trip cost in excess of £10,000 adjusted for inflation. The ultra-premium air travel market wasn’t big enough in the 1980s or 1990s to bear the costs of 1960s technology, leading to Concorde’s retirement in 2003.

Other European projects have lacked the centralised control or clear rationale that characterized Airbus.

We see this in Unidata, a 1973 consortium that brought together CII (France), Philips (the Netherlands), and Siemens (Germany) to produce a European mainframe line to rival IBM. With no clear leadership, rival members of the consortium pushed their own hardware and software approaches. Engineering efforts were duplicated. The project collapsed within two years amid recriminations.

Meanwhile, it was unclear why the 2005 Franco-German search engine project Quaero ever needed to exist. Widely seen as a vanity project at the time, the attempt to build a search engine by committee similarly splintered along national lines. It was also a victim of mission creep, evolving from a direct Google competitor to a multimedia search platform that would be powered by image and voice analysis. The project limped on until its mercy killing in 2013.

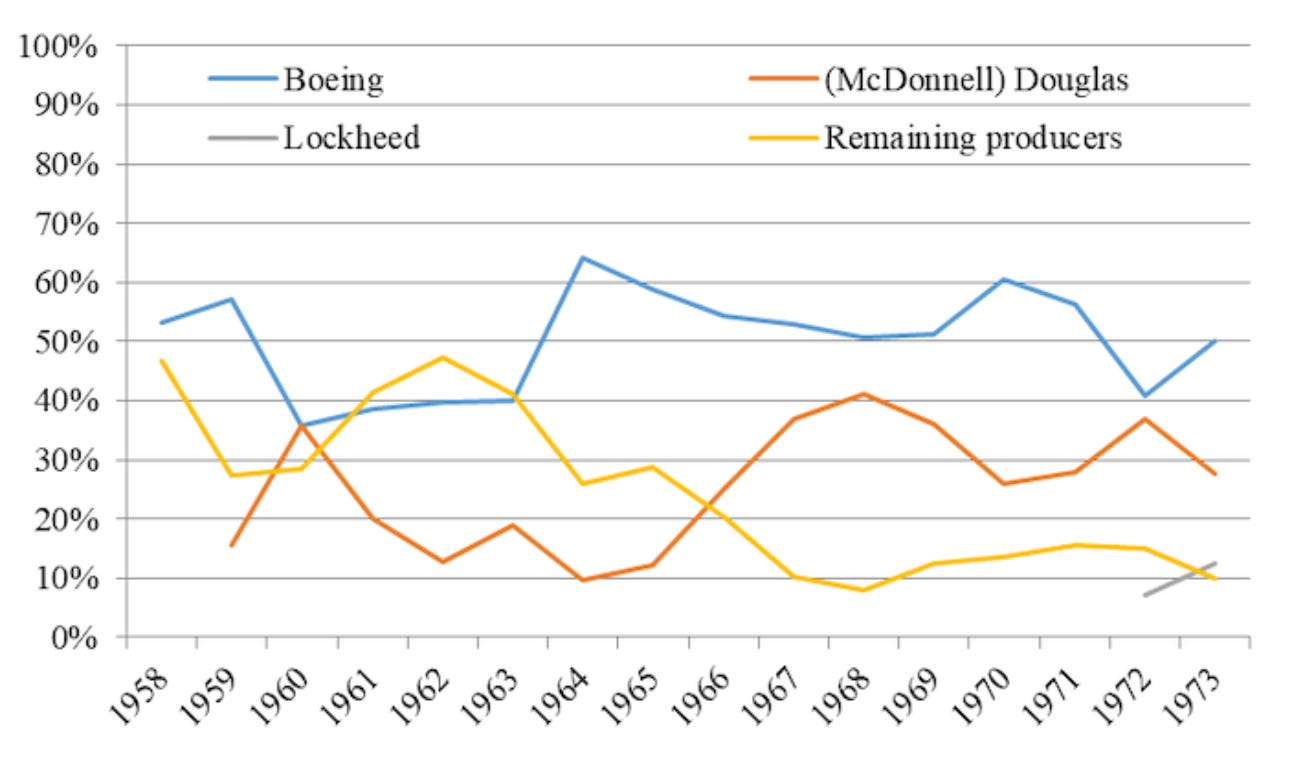

It’s also easier to build a global leadership position when your main rival wages a prolonged campaign of self-sabotage. By the new millennium, the competition had been reduced to a simple showdown between Airbus and Boeing. Lockheed had decided to bail on commercial aviation in the 1970s after losing billions of dollars on the L-1011, while Boeing acquired McDonnell Douglas in a $13 billion deal in 1997.

While Airbus has retained a strong engineering culture at the helm, this disappeared from Boeing. Harry Stonecipher, Boeing’s CEO in the early 2000s, notoriously claimed that: ‘When people say I changed the culture of Boeing, that was the intent, so that it is run like a business rather than a great engineering firm.’

Stonecipher’s successor, James McNerney, took this even further: ‘Every 25 years a big moonshot… and then produce a 707 or a 787 - that’s the wrong way to pursue this business. The more-for-less world will not let you pursue moonshots.’

The McDonnell Douglas acquisition is often marked as a turning point for Boeing. Despite being the acquiring firm, Boeing absorbed much of their target’s management philosophy. This disconnect was embodied in the company’s decision to move its headquarters from Seattle (where its main production facility was located) to Chicago, for the sake of just $63 million in tax credits. Fatal crashes in 2018 and 2019 have since caused regulatory investigations and multi-billion dollar compensation claims to pile up, as well as allegations that the company has put shareholders and dividends before safety.

A strange industry

Does the Airbus story make a good case for a disciplined, well-executed industrial strategy?

To answer this question, we need to take a step back from Airbus and Boeing and think about their customers.

Airlines have one of the worst business models of any industry. They have eye-watering capital expenditures (a large jet costs in excess of $200 million). The product offering (flights) is relatively undifferentiated, while many of their customers are price-conscious and disloyal. Safety regulations, along with route and landing slot regulations mean there’s little space to drive painless efficiencies. This leaves airlines with two main routes to success: worsening their service through cost-cutting and engaging in kamikaze price wars.

This is why airlines frequently go bankrupt, with US Airways, United Airlines, Northwest Airlines, Delta Air Lines and American Airlines among the dozens to almost collapse in the 2000s. Only three airlines without state ties (Southwest, Ryanair, and Copa) have consistently maintained profitability while avoiding bankruptcy or major restructuring.

In his 2007 letter to Berkshire Hathaway shareholders, Warren Buffett described the airline industry as ‘the worst sort of business’, and noted that, ‘if a farsighted capitalist had been present at Kitty Hawk, he would have done his successors a huge favour by shooting Orville down’.

Airbus, as a supplier to these businesses, has not been immune to these pressures. In the early 2000s, airliners were enthused about the ‘hub and spoke’ model. Passengers would fly on large aircraft between major hubs, then transfer to smaller aircraft for their final destinations. With a maximum capacity of over 800, the double-decker Airbus A380 would help allow airliners to consolidate their flights between busy international hubs. By the time it entered commercial operation in 2007, fashions had reversed and consumers were willing to pay a premium to fly direct. Airbus never came close to recouping its $25 billion development costs.

Against this backdrop, companies like Airbus and Boeing face a constant downward price pressure, operating on single digit margins in good years. The merry-go-round of buyers as airliners fall in and out of bankruptcy makes them fickle customers. With this in mind, Boeing’s desire to slash costs seems like a much more rational response, even if its execution was flawed.

It may be nearly impossible to operate the multi-billion dollar, multi-decade product development cycle this industry requires without some form of government backstop, whether it is a direct subsidy (Airbus) or reliable military orders (Boeing).

It is a business that is well-suited to subsidy for other reasons too. Governments are generally better at supporting companies in established markets where innovation takes place slowly and incrementally. This is likely why state-backed efforts have found it easier to be competitive against aerospace companies than Silicon Valley giants working at breakneck pace to keep pace with changing consumer tastes.

We can learn from Airbus’s engineering ingenuity and relentless customer focus. But its success in such an idiosyncratic sector probably isn’t as template for successful industrial policy in many of the other sectors that some people would like it to be.