We’re hosting a Stripe Press pop-up coffee shop and bookstore on Saturday, June 28, in Washington, DC. RSVP here if you can make it.

Over 90,000 Americans are waiting for kidney transplants, with thousands dying each year. For those who get dialysis, the treatment is painful and exhausting. Thirty-seven percent of patients were forced to quit their jobs. The five-year death rate is similar to brain cancer.

Now, over 40 years since the National Organ Transplantation Act of 1984 made compensating kidney donors illegal in the United States, there might be hope. The End Kidney Deaths Act, a new piece of legislation to offer a $50,000 refundable tax credit to all non-directed kidney donors, spread out over five years. It has gained bipartisan support and a steadily growing number of cosponsors, including most recently Speaker Emerita Nancy Pelosi. This will hopefully be the year when compensating kidney donors becomes possible again.

The kidney crisis keeps getting worse

The current system of kidney donation based on goodwill has failed. Living kidney donations have stayed flat at around 6,000 per year for a quarter century despite the growing waitlist: 9,000 people were on the kidney waitlist in 1984, while 90,000 are waiting now. From 2010 to 2021, over 100,000 Americans died while on the kidney waitlist or became too sick to remain eligible.

When any form of compensation for kidney donors was banned in 1984, the lead sponsor, of the legislation, then-Congressman Al Gore, acknowledged the possibility that a purely altruistic system might be insufficient, and argued that if voluntary donation efforts failed to meet demand, tax credits should be considered as an alternative approach. After four decades of persistent shortages, we have sufficient evidence to conclude that the current system is inadequate.

We also now know empirically that compensating donors will work. Unlike most countries that rely solely on unpaid donations, the U.S. permits up to $1000 per month as compensation for plasma donors. This policy has been remarkably effective. America supplies approximately 70 percent of the world's plasma needs through its paid donor system, exporting this vital medical resource to countries that lack sufficient domestic supply due to their donor compensation prohibitions.

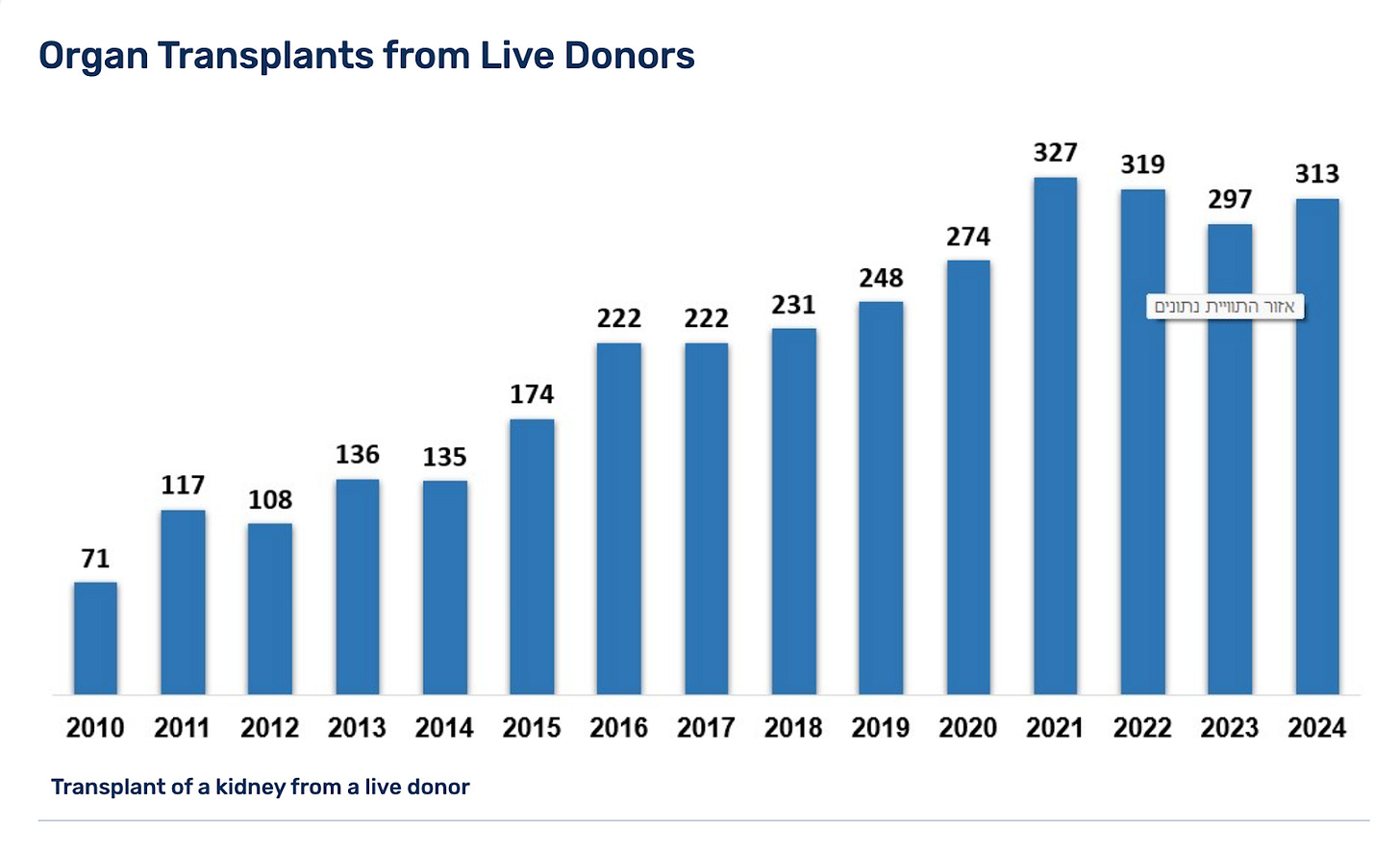

There is evidence from kidney donations, too. Israel, now the worldwide leader in living kidney donations per capita, enacted a 2008 law providing living organ donors with a month's paid salary and lower health insurance premiums. This reform, combined with nonprofit recruitment efforts, has made Israel unique: in 2022, about 50 percent of all transplants came from living donors, compared to just 15 percent in the United States. In the US, New York increased their living donation rates by 52 percent by merely reimbursing donors for out-of-pocket expenses up to $10,000.

How the End Kidney Deaths Act would work

The End Kidney Deaths Act (H.R. 9275) would establish a five-year refundable tax credit for non-directed living kidney donors – those who donate to strangers rather than to friends or family members. Donors would receive $10,000 annually for five years ($50,000 total) after surgery. These staggered payments are an important safeguard, as it reduces the potential attraction of kidney donation to financially desperate people in need of an immediate payout.

The tax credit is refundable, which means donors receive the full value regardless of their tax liability. This makes the incentive equally accessible across income levels, unlike standard tax credits that only benefit those with sufficient taxes to offset.

In addition to the human cost, the kidney shortage is a massive financial drain. End-stage renal disease occupies a unique position in American healthcare policy. Since 1972, it has been the one of two specific conditions (the other being ALS) for which Medicare provides universal coverage regardless of age, and without the standard 24-month waiting period for Social Security Disability Insurance. Effectively, a limited form of medicare for all. Congress made this exception in 1972 because the treatment for kidney failure, dialysis or transplantation, is essential, costly, and often not covered by private insurance.

Currently, approximately 550,000 Americans receive Medicare-funded dialysis, costing around $82,000 per patient annually. This expense consumes over one percent of the entire federal budget, or more than six times NASA's budget. Because transplants are much cheaper than dialysis, eliminating the kidney shortage by compensating donation would likely save taxpayers tens of billions of dollars.

What’s taken so long?

The four-decade delay in reforming kidney donation policy stems primarily from institutional resistance to change. Living kidney donation peaked in 2004 and has stagnated or declined since, despite technological and medical improvements. The current system does not expand access to living donations. The 1984 framework has remained largely unaltered despite mounting evidence of its inadequacy.

When compensation does get discussed, one counterargument tends to come up more than others: that donation would unduly commodify the human body, hurting the dignity of kidney donors. In other words, kidney donors should be donors, not vendors.

The opposite is actually true: kidney donors have been leading the charge for the End Kidney Deaths Act because they feel neglected by the current system. Everyone in the transplantation process – doctors, hospitals, coordinators – receives payment except the donor. Donating a kidney is safe, but it’s stressful, time-consuming, and painful. Offering compensation to kidney donors would honor the gift they are making.

Elaine Perlman is the President of the Coalition to Modify NOTA and Executive Director of Waitlist Zero

Duncan McClements is a fellow at the Center for British Progress and the Adam Smith Institute.

Jason Hausenloy is an independent AI policy researcher.

Thank you for raising these concerns. The End Kidney Deaths Act does not create a market for organs. Coercion and organ sales would remain illegal and strictly enforced.

Kidney donation is not easy. It is time-consuming, painful, and stressful. It involves around 6 months of testing, major surgery, and recovery. It is morally right to compensate people for difficult, meaningful work.

Importantly, only about 2 percent of those who come forward to donate actually go through with it. Most are medically disqualified after undergoing rigorous physical and mental exams. That means there will be no flood of vulnerable people donating just for the money. The process is and will remain careful, thorough, and safe.

We already pay people to do risky, lifesaving work. We offer tax breaks to encourage adoption and renewable energy. These are incentives for choices we value as a society. A tax credit for those brave and compassionate enough to have a major surgery to save the life of someone they don't know is no different.

Around 100,000 people are waiting for a kidney. Half will die before one becomes available until the End Kidney Deaths Act passes. The current system favors those with means. A better system protects donors, respects their courage, and gives more people the freedom to help.

It just doesn’t make sense that everyone in the transplant process gets paid except the actual donor. The person who’s going through surgery, recovery, time off work, and a lifetime of follow-up appointments gets...a pat on the back? That’s not dignity. That’s neglect.

Offering $50K over five years isn’t “buying” a kidney. It’s saying: we see what you did, and we value it. Stretching it out over time also makes it clear this isn’t about quick cash grabs,it’s a real thank-you that helps offset the cost of doing something incredibly selfless.

Also, the money we’re already spending on dialysis is wild. Over $80K a year per person, and we’re doing that for hundreds of thousands of people. If paying donors can help even a fraction of those folks get a transplant instead, that’s a win for them and for taxpayers.

I don’t get why it took this long. We already pay people for plasma, for bone marrow, even for being in clinical trials. But giving someone a kidney to save their life? Still treated like a moral taboo. This law is long overdue.