Last week, we released our first article from Issue 19, on how the FDA secretly liberalized animal drugs.

London is celebrated for its garden squares, of which several hundred were laid out in residential areas from the seventeenth to the nineteenth centuries. Some unfortunate tourists only visit the horrible Leicester Square, but most of the garden squares are genuinely nice, from the famous West End ones like Bedford Square and St James Square, to obscure places like Arlington Square in Islington or Cleaver Square in Kennington.

Virtually all these squares were laid out by private developers. This might seem puzzling. Although developers often imposed service charges on the residents of the houses they built nearby, these were normally sufficient only to cover the gardens’ maintenance costs, not to generate a profit. So landowners were incurring a large opportunity cost by turning land into revenue-neutral gardens rather than profitable housing.

The explanation, of course, is that the garden squares increased the value of the houses that surrounded them, and to a lesser extent of the houses in nearby streets. They did this so much that the increased profit from those houses outweighed the foregone profit from the gardens. This led generations of ruthless profit-seeking housing developers to acquire a sideline in landscape gardening.

The essential condition for this was that the developer owned enough land that devoting part of it to a garden square was net profitable. There had to be enough potential houses left over after some of them had been sacrificed to the garden that the sum of their increased value would outbalance the garden’s opportunity cost. In other words, garden squares would only develop if there was relatively unified land ownership. This is borne out empirically: areas developed under unified ownership have lots of garden squares (e.g. Marylebone), while areas developed under fragmented ownership have none, even where they are wealthy and residential (e.g. Hampstead).

This is an example of a hugely important phenomenon in the economics of urban design. Where there is unified ownership, developing landowners have incentives to provide public goods. They lay out generous interconnected street networks; they provide parks, gardens and street trees; they curate the facades and front garden of each building to ensure it presents a gracious aspect onto its neighbors; they devote land to shopping parades that produce relatively little revenue, and to churches and community buildings that produce none at all. None of these things happen when neighborhoods are developed under fragmented ownership, unless the public authorities intervene to ensure that they do.

Unified ownership often involves some people becoming very rich, as the profit from developing large areas of land accrues to single individuals or families. But this is not essential to the phenomenon. Much of the neighborhood in the foreground of this picture, South Kensington, was developed by an obscure Tudor-era foundation called the Henry Smith Charity, which continues to spend its vast profits on grants to reduce social and economic disadvantage. Other parts of South Kensington were developed by the Crown Estate, a publicly owned body whose profits are mostly spent on Britain’s public services or redistributed to poor Britons through the welfare system. In countries such as South Korea and Spain, mechanisms exist to let fragmented smallholders pool their land into development cooperatives. The important point is that large areas are developed under a single authority with an incentive to maximize their value as a whole, not that the resulting profits should go to a single individual.

One of the perennial problems of urban life is that land ownership normally fragments when the development is complete and the new properties are sold to their occupants. This means that neighborhoods with a unified landowner up to the point of occupation start to suffer the collective action problems of fragmented land ownership afterwards. Nobody wants to be the one who pays for public goods. And many people might like to do things on their plot that maximize its value even while blighting its neighbors. Urban politics is, among other things, a long-running attempt to solve this problem through forcing fragmented property owners to contribute to public goods and abstain from activities that harm the city as a whole.

There are, however, some interesting cases where property ownership does not fragment at the point of occupation, and where unified landowners continue to provide services that we normally expect to receive only (if at all) from local government. In the rest of this article, I will tell some stories of this. I have chosen stories from my own country, because I know them well and can tell them better. But it will be obvious that the basic pattern of incentives I describe will occur anywhere that unified land ownership is preserved beyond the point of occupation.

The village without cars: Clovelly. Clovelly is a seaside village in Devon. It is one of the world’s most picturesque experiments in microeconomic theory, being entirely owned by a single family, the Hamlyns, who have managed it since the eighteenth century.

Management by the Hamlyns has led to Clovelly evolving in ways drastically unlike most English villages. For one thing, Clovelly has pursued perhaps the most radical pedestrianization policies in Europe, completely banning cars from the village, which can only be entered on foot. Freight was historically transported by donkeys, now replaced by sledges. Clovelly’s steep and narrow streets remain some of the most picturesque public spaces in England as a result. Each property is carefully maintained, with climbing plants and hanging baskets of flowers.

This strategy has been highly successful in making Clovelly a tourist attraction: the town’s website proudly notes that it is ‘Britain’s most Instagrammable village’, with more hashtags than any other. Somewhat surprisingly, however, the Hamlyns have completely prohibited holiday homes, exclusively letting residential properties on long leases to permanent inhabitants. The theory seems to be that Clovelly’s appeal rests on being a living Devonshire fishing village, not a cluster of AirBnbs. This means systematically refusing the highest bids for individual properties in order to preserve the value of the village as a whole.

Curating De Beauvoir Town. De Beauvoir Town is a neighborhood in Hackney, in Inner London. Although few Londoners have heard of it, any visitor will immediately notice its appeal upon entering. Its properties are exceptionally well maintained, even when they sit on heavy arterial roads. It has a pretty shopping parade with tasteful wooden fascia and elegant shop fronts. Properties in De Beauvoir command a substantial premium, and it is standard practice for local estate agents to falsely claim that anything within half a mile of the actual De Beauvoir Town is ‘in the heart of De Beauvoir’.

Attentive visitors will notice something else, which is that about a third of the buildings in De Beauvoir – and generally the best maintained – have handsome dark blue front doors. This is the color of the Benyon Estate, the original landowners in the nineteenth century. Unlike most London landowners, the Benyon Estate never completely sold off their stake in the neighborhood, and in recent decades they have been increasing it again. It lets its properties on secure permanent leases, and is known for acting swiftly and effectively on maintenance requests from tenants.

The Estate follows a distinctive investment strategy. It regularly buys up properties in De Beauvoir when they come onto the market, but only if the properties are in bad repair and need extensive refurbishment. The Estate’s theory is that it not only gets the profit on refurbishing a property, like any other developer, but also the profit from removing a blight on all the neighbors. Because it owns a large share of those neighbors, refurbishing property in De Beauvoir is a uniquely good investment for it. Over time nearly all the decayed properties in De Beauvoir have been refurbished by the Estate and are now maintained by it, making the neighborhood a uniquely smart area of East London.

Densification on Cundy Street. One of the problems with densifying existing urban areas is that densification normally takes place under conditions of fragmented ownership, because the ownership of most existing urban areas fragmented when they were first developed. In the ideal version of densification, floorspace would be added to each individual plot in a way that did as little damage as possible to the value of its neighbors – or, if possible, in a way that enhanced them. But under fragmented ownership, each property owner’s incentive is to add as much value to their own plot, regardless of its impact on neighbors. Densification under conditions of fragmented ownership may still be a net good, but it will generally be less good than it would have been if it had been planned with a view to maximizing neighborhood value.

The rare cases in which densification takes place under unified ownership are thus of exceptional interest. In the eighteenth century, for obscure historical reasons, it became normal for new English neighborhoods to be sold into ‘leasehold’. This meant that they were not sold permanently, but rather on long leases of between thirty and a hundred years, after which they reverted to their original owners. These owners were known as ‘Great Estates’, and their residual stake in the property was called the ‘freehold’. By the late nineteenth century, a majority of urban England seems to have been owned by Great Estates, perhaps as much as eighty percent of it. (The best books about the Great Estates are this and this. The best study available online is this.)

The leasehold system meant that a single landowner retained a permanent stake in any given neighborhood, with an opportunity to redevelop it at higher densities under conditions of unified ownership when the leases fell in. This happened frequently in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, generating the dense but harmonious fabric of neighborhoods like Knightsbridge and Mayfair.

Most of the Great Estates were dismembered in the twentieth century. Some were sold off to pay inheritance tax, and all were forced to sell many freeholds to leaseholders (‘leaseholder enfranchisement’). This dismemberment was not, however, quite universal. A few Great Estates have partly survived, especially in London’s West End, where they continue to furnish us with picturesque illustrations of microeconomic theory in action. One of them, the Grosvenor Estate, is currently providing a fresh illustration of how a unified property owner can do densification better at a site on Cundy Street, near Victoria Station. An entire street block of 1950s apartment buildings is being demolished, to be replaced by a much denser mixed-use development.

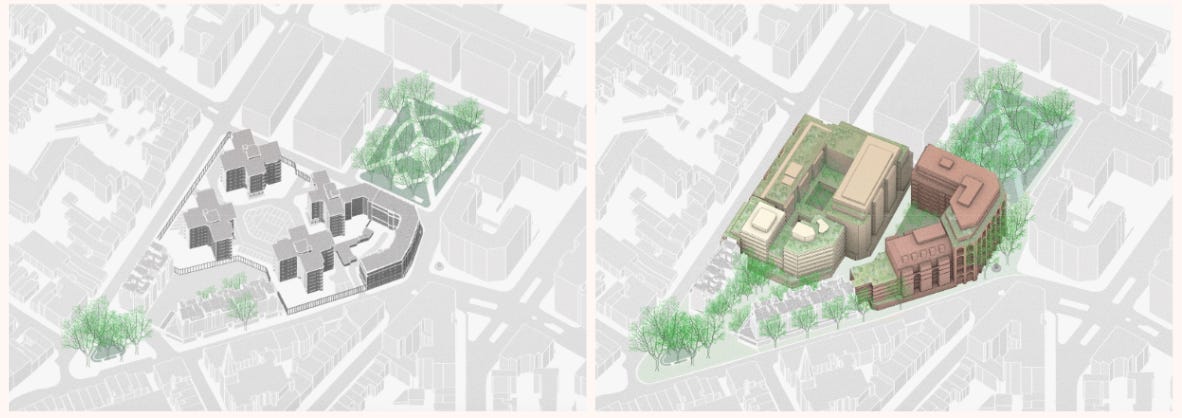

Unified ownership manifests itself here in two ways. First, it means that Grosvenor can change the overall structure of the block, repudiating the ‘tower in field’ pattern of the 1950s and returning to the traditional ‘perimeter block’ model. In the middle of the block, a new garden square is being created. This would be impossible if the block were divided into separately owned plots that were being developed separately. Second, it means that Grosvenor is incentivized to improve the impact of the development on the wider neighborhood, much of which Grosvenor also owns. The facades of the development are among the best of any comparable British development in living memory, vastly enhancing the streetscapes on all sides. It is doubtful that the landowners would invest so generously in the neighborhood if they had no stake in it.

Pedestrian improvements on Sloane Street. Sloane Street is one of the world’s premier shopping streets. But, as in so many places, expensive shops and often excellent architecture have historically lined a degraded and unpleasant public realm, a hard tarmacked space dominated by arterial traffic. At its southern end, the street empties into Sloane Square, technically one of London’s garden squares, but really a kind of glorified traffic island.

This has just changed. Pavements have been widened, and paved with traditional sandstone. A hundred trees have been planted, junctions have been narrowed, and unusually tasteful street furniture has been introduced. Sloane Square is being remodelled to make it friendlier for pedestrians, with wider pavements and better crossings.

The entire bill for this, running to around £50 million, is being paid by a single local landowner. This is the Cadogan Estate, another of London’s vestigial Great Estates that lingers on in this bit of West London. The Cadogan Estate cannot charge for use of the Street or the Square, and indeed it does not even own them. But it still owns so much property nearby that it has apparently concluded that the benefit it derives from improved public realm makes it worth paying for. The official local government, the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, need only allow the Estate to provide the public goods that would normally be its responsibility. And the rest of us can enjoy the results as free riders.

Recreating a Great Estate in Shoreditch. As we have seen, land ownership in modern English cities has tended to fragment over time, either at the point of occupation or because the government has subsequently redistributed it. The same pattern is evident across the world. Under certain conditions, however, the advantages of unified land ownership have been so overwhelming that it has begun to re-emerge.

We see an example of this in Shoreditch, a historically industrial neighborhood just north of the City of London (the financial district). For several decades, the Harbour and the Bard families have been investing in property in this neighborhood, until between the two of them they owned almost an entire street block. They then joined forces, and last year they applied for permission to redevelop the site.

The proposed redevelopment is in many respects a model case of densification. New pedestrian alleys will be threaded across the huge block, improving the pedestrian permeability of Shoreditch. Another garden square will be created at its core, providing pleasant views for the apartments, offices and restaurants that surround it, and a pleasant meeting point for everyone who lives and works nearby. Remarkable pains have been taken over facade quality, generating architecture that is partly a re-imagining of Shoreditch’s Victorian warehouse vernacular, and partly an Art Deco revival. None of this would be possible if ownership of the whole block had remained in fragmented ownership.

We at Works in Progress have a lively interest in this project, because it is just across the road from our office. We do not, alas, own any of Shoreditch Works ourselves. But when ownership is unified, private developments are prone to creating public goods. And in this case, ‘the public’ is us.

Part of the moral is obvious. Unified land ownership has a lot of advantages. If you’ve got it, you should consider keeping it. If it is re-emerging naturally, you may not wish to strangle it. The more complicated question is what to do where unified ownership does not exist, or where it has been irrevocably lost. We have some answers to this question. But they will have to wait for forthcoming issues of Works in Progress.

Samuel is an editor at Works in Progress. He focuses on urbanism and cities. He has previously written The beauty of concrete, Making architecture easy, Against the survival of the prettiest, and In praise of pastiche for Works in Progress.