Issue 20: The death rays that guard life

Plus: How to make antibodies, why rivers are now battlefields, and a clinical trial for cooling the plant

Works in Progress Issue 20 is out today.

Our spotlight piece explores how using modern germicidal light can allow us to make indoor air safe at scale, in the same way we have with water. The common cold and winter flu might soon be behind us.

We also have pieces on:

Slowing climate change by dimming the sun;

Manufacturing antibodies at scale;

How upstream nations hoard water with dams;

The story of France’s record-breaking nuclear buildout; and

The fashion for ‘systems thinking’ and why it’s overrated.

Yesterday, we announced that Works in Progress is becoming a print magazine, with our first print issue, Issue 21, landing in November.

You can subscribe from the United States and the United Kingdom today, and we’ll be adding Canada, Australia and the whole European Union between now and the release date in November. An annual subscription will cost $100 in the United States and £75 in the United Kingdom. To subscribe, click here. If you live outside the US or UK and want to be notified as soon as subscriptions are live in your country, leave your details here..

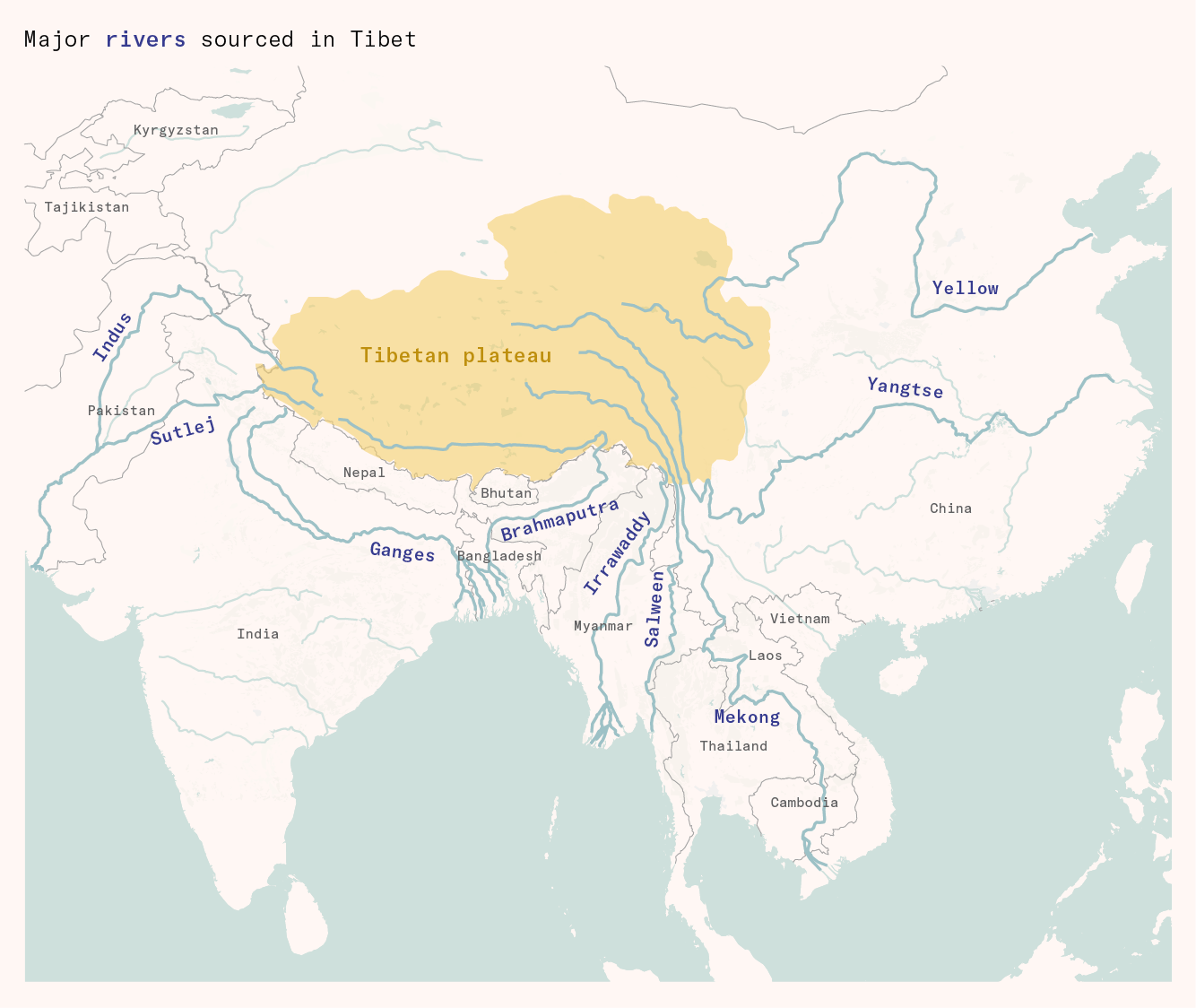

Rivers are becoming battlefields, writes Connor Tabarrok. India’s suspension of a single treaty threatens to choke off the water that irrigates four-fifths of Pakistan’s farmland, while China’s control of freshwater chokepoints in Tibet give it leverage over nearly two billion people downstream. The rise of hydroelectric power secures electricity for upstream states, while leaving others at their mercy. A potential solution lies in desalination, which has become radically cheaper as technology has improved. This might help vulnerable nations secure their own reserves and escape the chokehold.

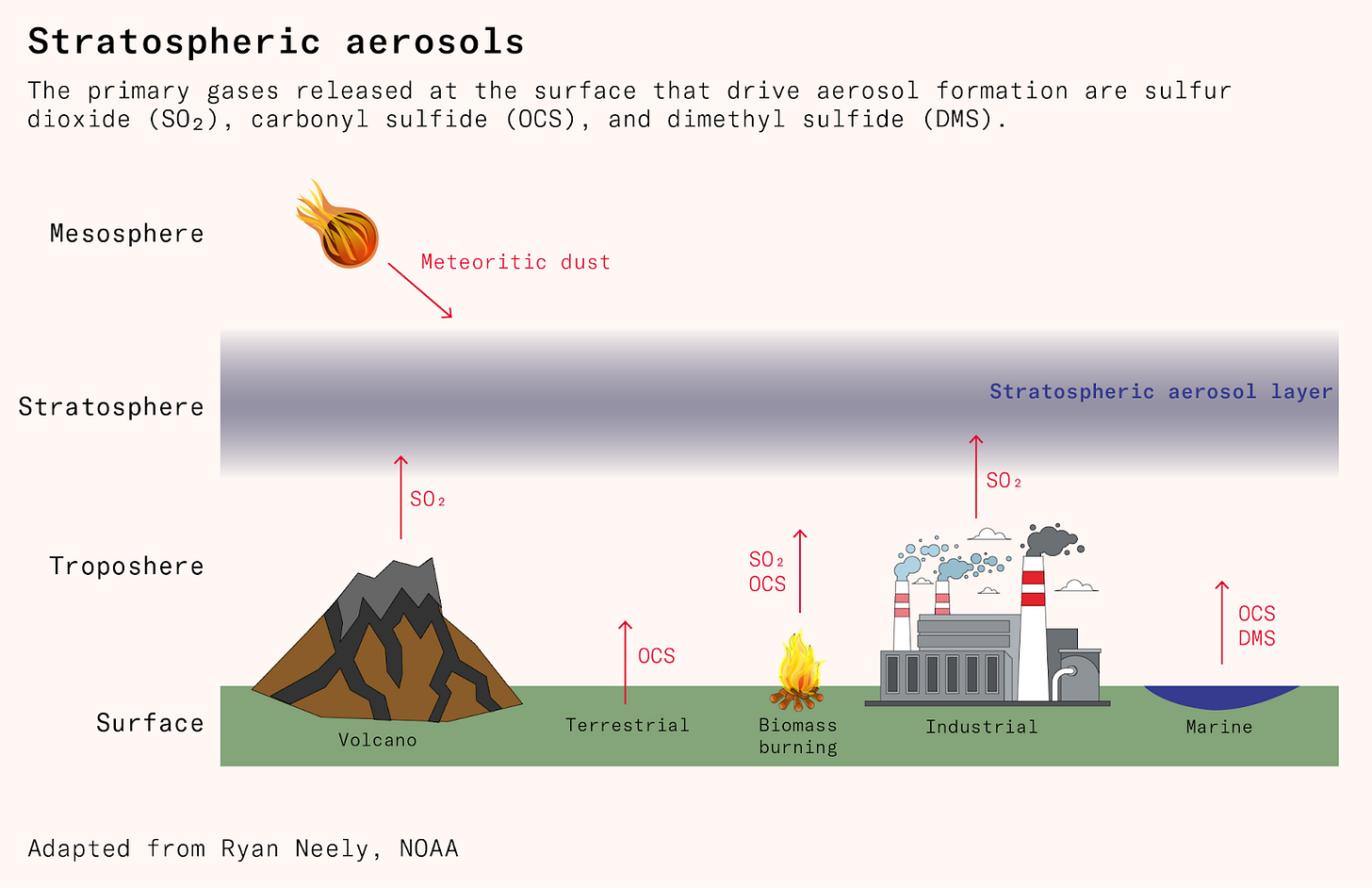

Current efforts to cut emissions aren’t keeping up pace with rising global temperatures. But aerosols from volcanoes reduce global temperatures by half a degree or more, and our pollution already dims the sun a little. As pollution declines, the warming they masked will surface. One option, write Dakota Gruener and Daniele Visioni, is to carefully imitate these processes by injecting small amounts of sulfur into the stratosphere, where particles spread globally and reflect sunlight. Doing so carries risks, so the solution may be to run a clinical-style trial, starting small and scaling up.

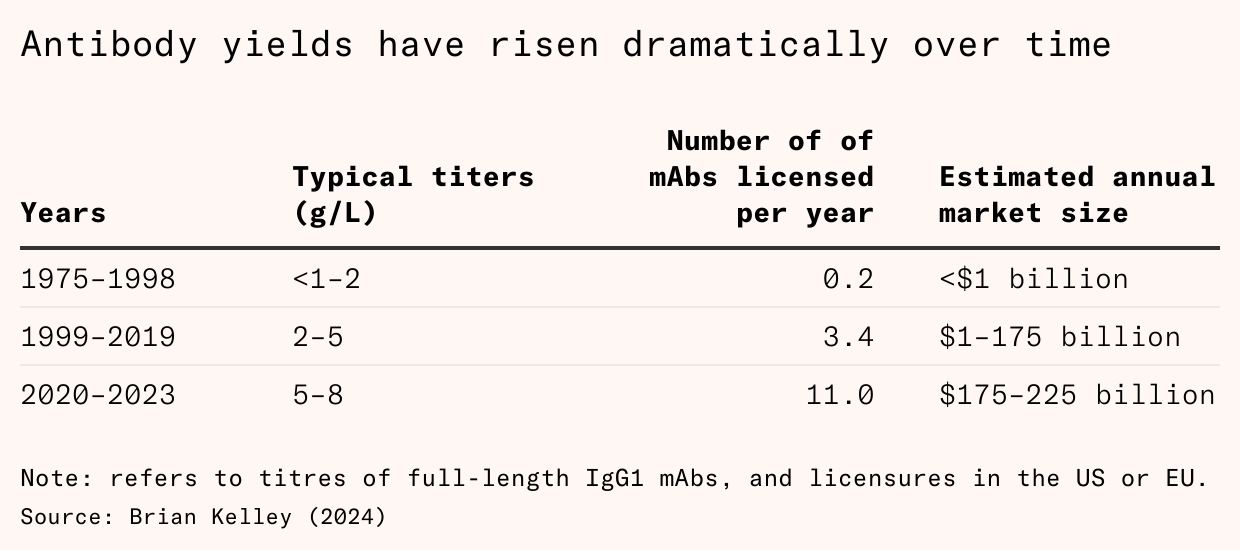

Today, antibodies are one of the most common types of medicines, treating autoimmune diseases, cancers, infectious diseases, and snakebites (as antivenom). But producing them at scale took mice bloated with tumors, gene-splicing technology, and industrial fermenter tanks. How did we get here? Alex Telford tells the story of how antibodies became a cornerstone of medicine.

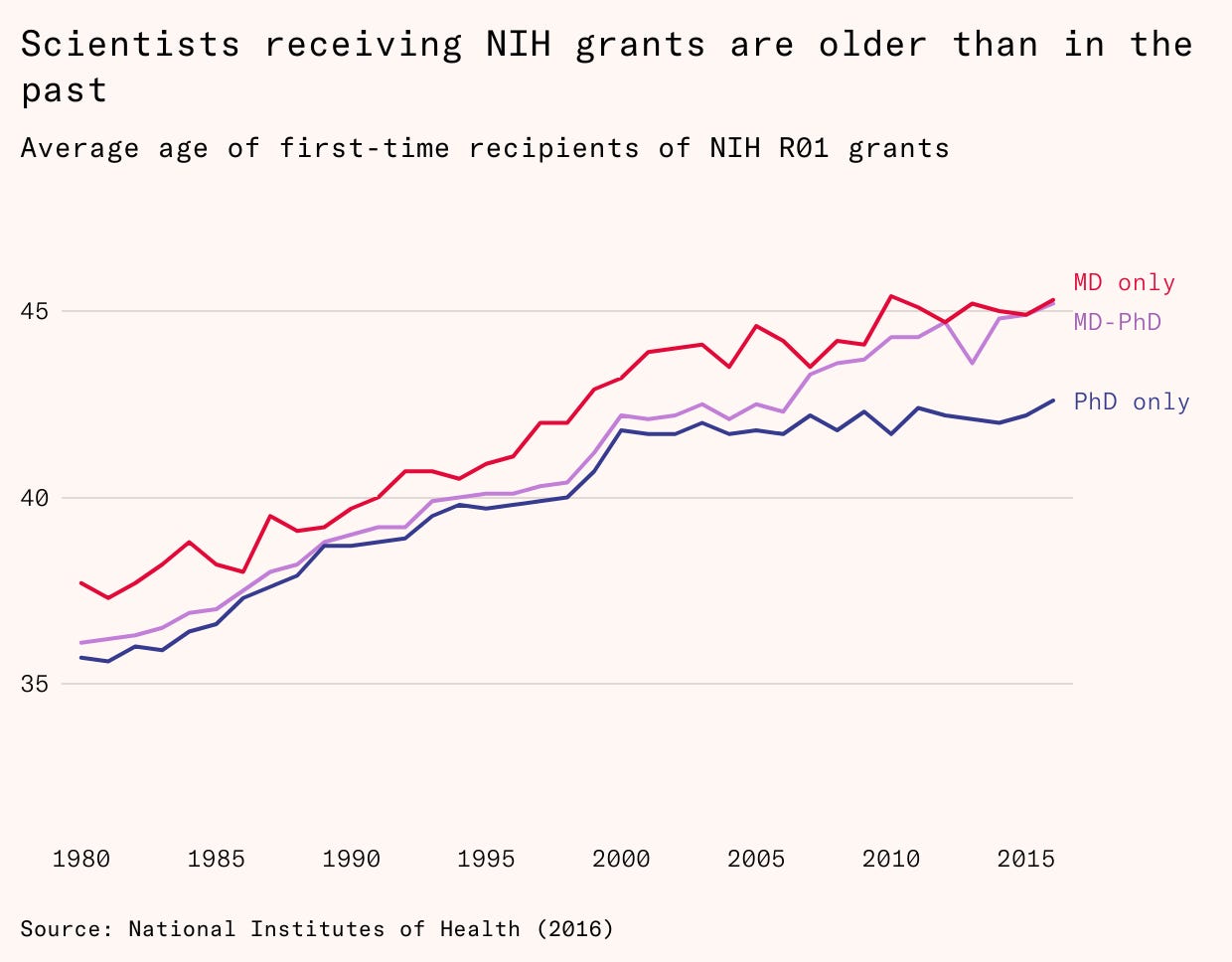

The history of scientific discovery is full of trespassers wandering into fields and reshaping them: a draper who worked out ways to magnify bacteria up to visibility; a clockmaker who solved longitude; a patent clerk who reshaped physics; a Hollywood actress who helped invent secure wireless. But academia has become worse at funding and hiring outsiders and suffers as a consequence. Alvin Djajadikerta and Laura Lungu suggest ways to bring science’s next outsiders back in.

Systems thinking has taken the policy and management worlds by storm because it promises control over complexity. But, as Ed Brandon tells us, these grand designs almost always fail: HealthCare.gov crashed on launch, Australia’s disability reforms cost far more than planned, and connecting new renewables to the British grid now takes 15 years. Each attempt to fix a failing system spawns new layers of rules, oversight, and unintended consequences. Success comes from discarding top-down planning in favor of projects that start small and expand gradually.

France managed to build over 40 nuclear reactors in the space of a decade, in one of postwar Europe’s most impressive industrial achievements. They did it, writes Alex Chalmers, by choosing one standard design, ordering in bulk, approving sites in advance, and streamlining regulation. Local communities received money and perks, weakening political pushback. As a result, France now gets 70 percent of its electricity from nuclear, has one of Europe’s greenest grids, and enjoys low energy prices.

Hiring

Works in Progress is still hiring someone to grow our audience, plus sell books and magazine subscriptions. We want to do everything we can to reach millions more readers.

We are also hiring a designer.

Notes on Progress

Evan Zimmerman on how market design fixed food banks.

Michelle Ma asks why the first non-opioid painkiller took so long to develop.

Samuel Hughes explains how Canada’s largest city developed a 30-kilometer network of pedestrian tunnels.

Austin Vernon and Ben Southwood make the case that batteries could make electricity grids stable without the need for expensive infrastructure.

Alfie Robinson explores how lead paint was outcompeted by a cheap alternative before it was banned.

Benedict Springbett on how trams can provide cheap transit in smaller towns.

Michael Ioffe on how better AI models, sensors, and data sharing could help us to predict earthquakes.

The Works in Progress podcast

The Studies Show podcast has joined Works in Progress and relaunched as Science Fictions.

The Works in Progress podcast has put out episodes on The Great Downzoning, the intangible economy, Henry VIII’s (bad) tax policy, the economics of land, politics in China, and feminism in East Asia.

After their five hour episode on the history of HIV drugs, Saloni and Jacob (aka Hard Drugs) have followed up with two short episodes on the world of proteins and the history of insulin.

What we’ve been up to

We ran Invisible College, a week-long summer school in Cambridge for 18–22 year olds which included talks on spatial economics, beautiful data visualization, the origins of the Industrial Revolution, scientific fraud and bias, and robotic dexterity.

Sam has spent the summer in the playground with his son and been reading about the Hundred Years’ War before bed. He wrote about why Europe has become so stagnant for Reason Magazine (and didn’t pick the title).

Ben has been reading through the catalogue of novelist David Mitchell, alongside editing and looking after his two children.

Saloni has been reading a lot of science history books, including The Code Breaker, The Butchering Art, and Genentech: the beginnings of biotech.

Rachel climbed the highest mountain in the British Isles, and has been reading CS Lewis.

Pieter travelled around India and the Caucasus. He also wrote about why Baumol’s cost disease might help Europe.

Aria got married.

Alex visited the most sectarian areas of Northern Ireland and was publicly reprimanded by the UK’s nuclear regulator.

Samuel spoke about win/win solutions to housing shortages at the YIMBYLAND conference in New Haven, and is speaking in France this week about why the survival of the prettiest theory is probably wrong.

Atalanta exhibited a painting of a naked youth riding a pig at Kristin Hjellegjerde gallery.

Happy reading (for even happier reading, subscribe to the print edition!)

– the Works in Progress team

Rivers are becoming battlefields, says Connor Tabarrok?

Conor ignores the real story of the Yarlung-Tsangpo project, misplaces it cartographically, calls it a mega-dam, then ices the cake by attributing evil motives to its construction.

It’s not on the Brahmaputra for one thing. The Brahmaputra is in India and the name change reflects the fact that it gets 80% of its water in India, which is India ubtroubled by its construction.

Nor is it a mega-dam. It’s a series of weirs whose upstream pools cover the intakes to the hydro plant below.

The engineering involved in extracting 3x more power than the 3 Gorges is mind boggling and deserves a great deal of attention but gets little.

Incidentally, it will recoup its entire construction, cost plus interest, 13 years after commissioning

I own an air filter than is cheap, quiet, and has low throughput. I've wondered whether a cheap UV light installed inside of it would help, or whether the exposure time is simply too short to matter. Do the filters themselves trap microbes temporarily, potentially extending UV exposure time?