Toronto's underground labyrinth

How Canada's largest city developed a 30 kilometer network of pedestrian tunnels

Toronto has one of the world’s great commercial downtowns. Two metro lines, eight suburban heavy railways, an extensive bus system, a highway, and North America’s greatest surviving tram network all converge on a tiny area by the shores of Lake Ontario. Hundreds of thousands of commuters pour into the downtown every day, filling the great towers that line its nineteenth-century streets.

As with many downtowns, this causes congestion. Streets and pavements are thronged at peak times. Bicycles, pedestrians, cars, trams and buses compete for scarce space. As with all traditional radial transport systems, there is an enormous concentration of movement in a tiny area. Pedestrians make slow progress across the urban fabric, stopping every block for a minute or two to wait to cross the road.

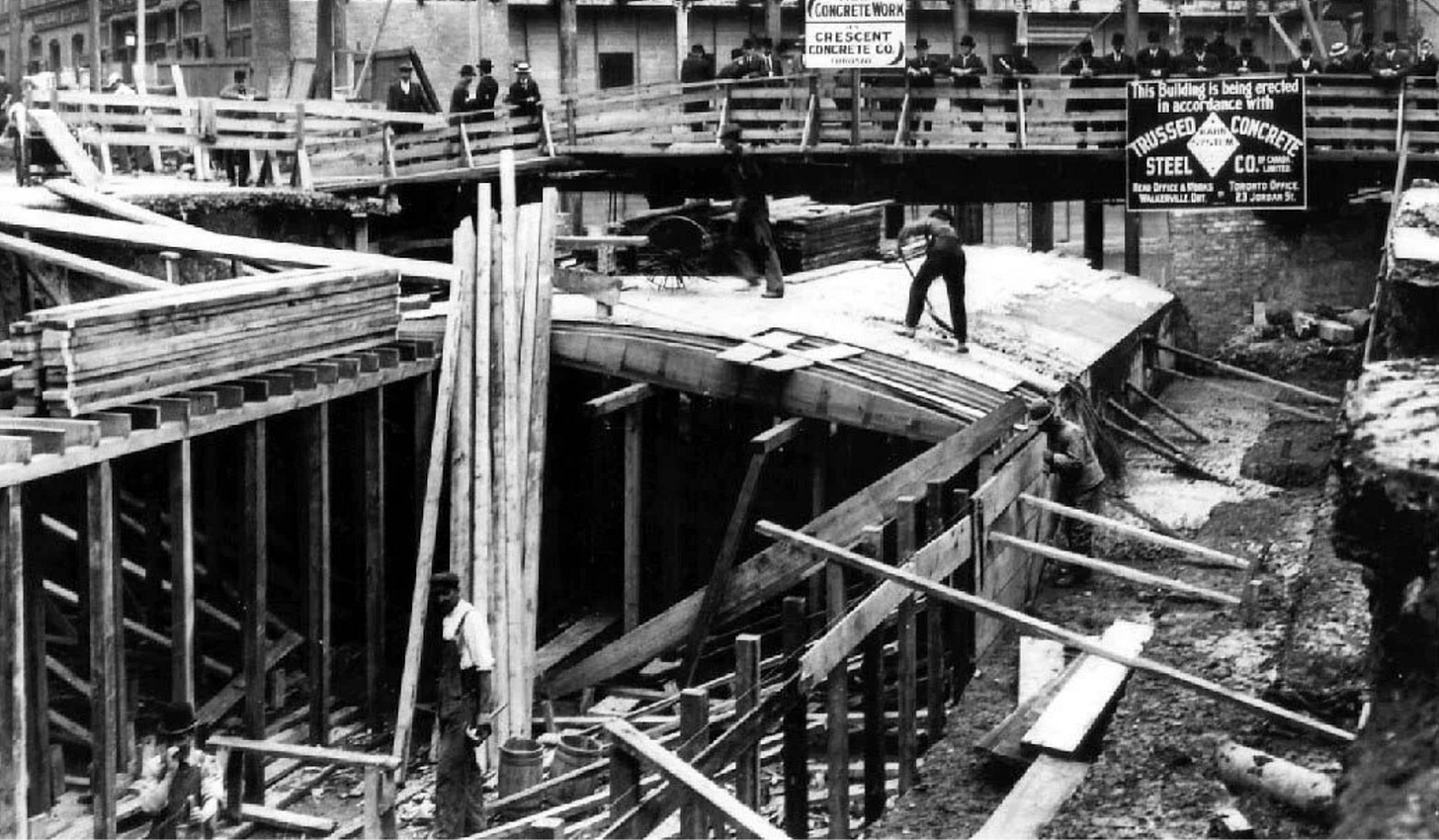

In the early twentieth century, Toronto’s businesses developed a novel response to this. They began to create pedestrian tunnels from their offices to the metro stations so that their employees could flow in smoothly, avoiding the congested streets (and, in winter, the cold). Shops quickly started to be added. After a few businesses had done this, a ‘network effect’ emerged whereby other businesses started to add their own tunnels to the system, benefiting from the existing tunnels while also making them more useful. It became routine for downtown developers to tie new office blocks into the network. Over many decades, a sort of ‘pedestrian metro’ emerged.

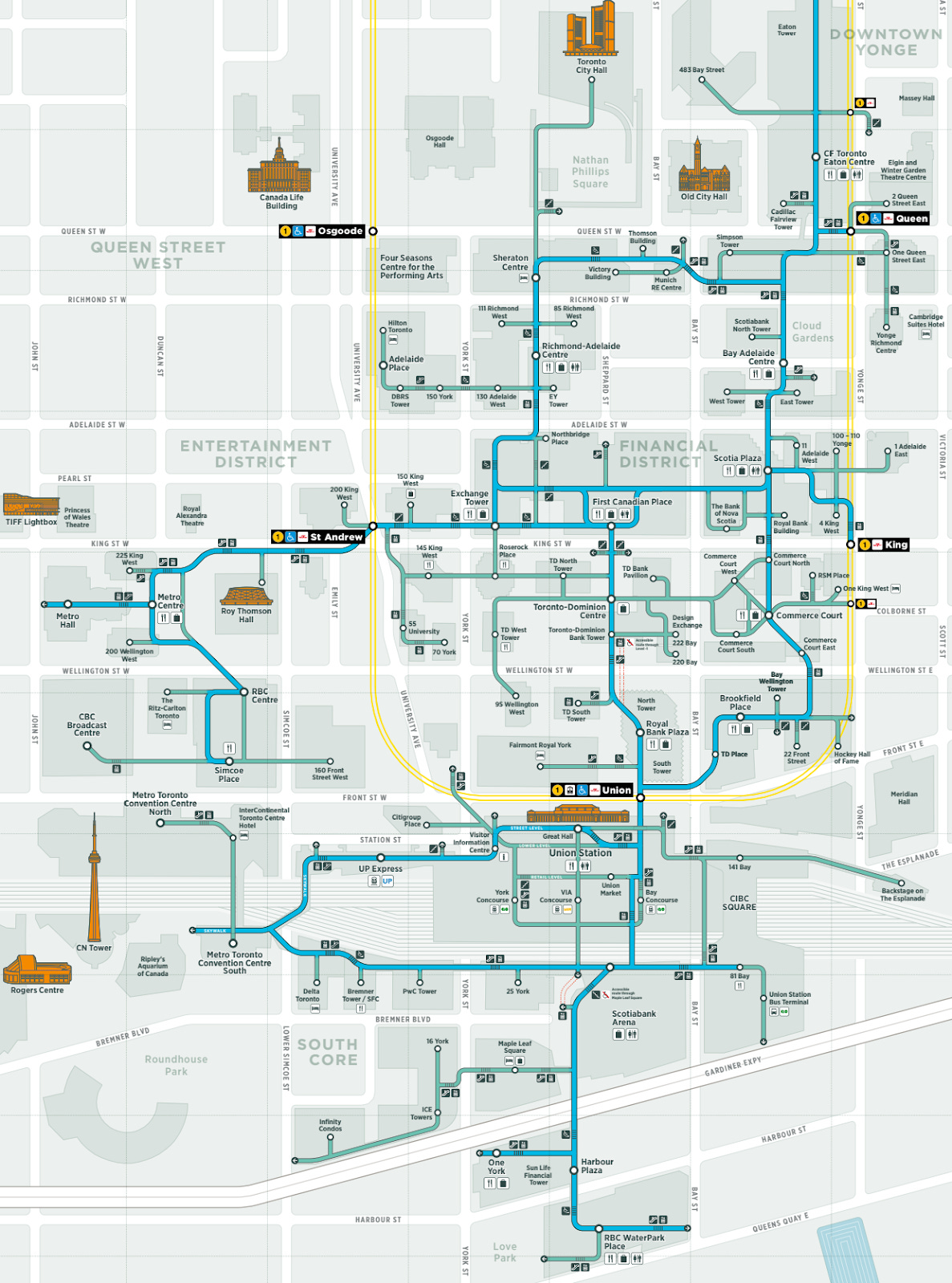

Known as the Path, the network today stretches for more than 30 kilometers, linking nearly all central metro and railway stations with many of the major office buildings. Although the Path forms a unified network, it is not in unified ownership: it is divided into some 35 chunks, each of which is still owned and managed separately by descendants of whichever business originally contributed it. Many branches of the Path thus terminate in the lobbies of office buildings, with the curious result that these grand spaces function as metro entrances for the general public. The municipal authorities play only a limited regulatory role.

The Path is unlike the gloomy and malodorous underpasses with which most of us are familiar. It is expensively decorated and feels like a high-end shopping mall, which in a way it is. It is extremely clean and closely policed by dozens of private security teams. Until recently, it was thronged with shoppers: this use suffered in the pandemic and has not wholly recovered, but the Path is still used for its original commuting purpose by hundreds of thousands of people every weekday.

Urbanists are normally sceptical about pedestrian tunnels, fearing that they kill off street life. This is a reasonable concern and may often be a decisive reason to avoid them. But in a downtown like Toronto’s, human density is so enormous that this worry seems exaggerated. The pavements of Toronto are still busy, even on weekends, despite hundreds of thousands of pedestrians going underground. The carriageways are still congested with vehicles. It is facile to see this as a simple trade-off between walking and driving. The Path frees up space for bicycles, buses and trams as well as cars. It complements the metro and railway system by shaving off five minutes from the station-to-office walk. The Path may well be substantially net positive for a radial system of public and active transport.

The Path is also interesting for what it tells us about transport economics. It is exceptionally unusual in forming an integrated network without having been developed by a single body. The equivalent would be a railway that was created piecemeal by uncoordinated landowners, with each adding small chunks until it stretched from one city terminus to another – a thing which, to my knowledge, has never happened.

There are at least two reasons for the Path’s distinctive economics. First, pedestrian tunnels are clearly exceptionally valuable to individual landowners, such that they are prepared to bear the entire cost of providing transport infrastructure from which other landowners could subsequently benefit. It wasn’t necessary for the whole network to exist in order for the first landowners to get started: in downtown Toronto, pedestrian tunnels are so good that there was no first-mover problem. This is generally untrue of transport infrastructure: for example, any given stretch of a railway is virtually useless until the entire railway is finished, which is why public authorities usually have to plan entire railways from the start.

Second, pedestrian tunnels have an extremely high upper limit on how many people they can take. As a famous 2003 advert illustrated, a human travelling in a vehicle requires space for their vehicle as well as themselves. A human travelling by foot does not, and is thus much more spatially efficient. This means that additional chunks can be added to the Path without normally creating ‘pedestrian jams’ in the existing stretches: there is nearly always space for more people. This is often untrue for roads and railways, where planners constantly worry that adding additional branches will cause congestion on central trunks.

This means the Path’s model isn’t easily replicable for other transport modes: roads and railways really do need unified planning. But it isn’t clear why pedestrian metros should be impossible in other cities. In fact, to some extent, they do exist. Montreal has a similar system, while Tokyo, Osaka, Seoul, Hong Kong, Singapore and Houston have systems that resemble the Path in some respects. A few European cities also make considerable use of pedestrian tunnels, including Helsinki, Stockholm and Munich.

Overall, though, the list of pedestrian metros is short. It would be interesting to investigate why this is. Why aren’t there pedestrian metros in Manhattan, Boston, Shanghai, Vancouver, Paris and the City of London? Is there some reason why the economics are different? Is the soil already too full of tunnels and utilities? Or are there regulatory constraints that might, in principle, be fixable?

Downtowns were one of the great triumphs of nineteenth-century urbanism. Where they have not been destroyed by cars and modernism and civic mismanagement, they remain enormously valuable urban forms today. But they present, and have always presented, unique and interesting transport problems. Maybe pedestrian metros have a role to play in solving them.

Samuel is an editor at Works in Progress. He focuses on urbanism and cities. He has previously written The beauty of concrete, Making architecture easy, Against the survival of the prettiest, and In praise of pastiche for Works in Progress.

Minneapolis has a skyway system which connects a bunch of buildings in its downtown with above-ground enclosed bridges, so that workplaces, shops and restaurants are all accessible by temperature-controlled pedestrian paths, often involving snaking through office hallways and up and down escalators. This is entirely motivated by reducing the need to be outdoors in the cold winters; Minneapolis is very low-density and car-centric compared to Toronto. But the dynamic you describe of private business owners piecing together a connected system out of self-interest is similar.

The City of London tried to take its pedestrians up in the sky with the Pedways, rather than underground. It was never especially successful.

Although nowhere near as extensive as Toronto's system, Canary Wharf has a similar vibe in its underground and enclosed malls. Makes sense given a lot of it was built by the Toronto-based firm Olympia & York.