We’re hiring someone in London to help grow Works in Progress's audience and sell Stripe Press books (and, soon, Works in Progress magazine subscriptions). If this could be you, please apply here!

Many cities face the following problem. They have railway lines that go where people live. But these railway lines end at the edge of the city center, and don’t go out the other side.

For cities with this problem, the solution is through running. Terminating a train and turning it around takes a lot of space, space that is usually unavailable in a city center. This means running a railway line through the city often doubles or triples the number of trains it can handle. As a bonus, passengers who are going from one side of the city to the other can do that much more quickly, with no change.

Many cities, such as London, Paris, Munich and Milan, have used through running to turn some of their existing Victorian railway lines into metro-style services, by building tunnels under the city center. A few other cities, like Berlin, built viaducts (bridges that carry roads and railways over obstacles), while others, such as Cologne, have simply added platforms at their main stations to enable suburban trains to run through. But all of these are big cities, with over a million people, where the property value uplift or extra revenues from fares can cover the enormous costs of tunneling. But there is another option, affordable for smaller cities or large towns: the tram-train.

Karlsruhe is a small city of only 300,000 people in southwestern Germany, near the French border. The city’s main station is nearly two kilometers from the city center, following a project in the early twentieth century to build a larger station on a less cramped site. This caused great inconvenience to passengers, who had to change to the city’s tram network in order to get to the old center.

In 1957, the city took the first steps towards creating a new type of transit, the tram-train, when it took over a bankrupt suburban railway, the Albtalbahn, and extended it into the city center over the tram network.

Over the next four years the line’s gauge (the space between the rails) was converted from 1,000 millimeters to 1,435 millimeters, the standard gauge used by the tram network, and it was re-electrified at the same voltage as the tramway. The modernization of the line enabled quicker journey times – the 70 minute journey to Bad Herrenalb, the line’s terminus, was reduced to 46 minutes – but more importantly passengers who wanted to get to the city center did not need to change to a tram.

The idea of a tram that runs outside of a city’s urban area was not new: Vienna, for instance, had been operating a similar line to the neighboring spa town of Baden since 1907. Karlsruhe’s inventive step, which came later, was to extend the tram-train onto railway lines that did not just carry tram traffic. In 1979, the line was extended onto a freight railway north of the city, and in 1992 the first tram-train took over pre-existing passenger services, to the town of Bretten.

Joining the tram and train networks together was tricky. German railways are electrified at 15 kilovolts alternating current, while Karlsruhe’s trams use 750 volt direct current, which meant that the city needed to procure trams capable of using both voltages, which were (and still are) rare. The railway and the tram network used two different signaling systems, the ‘traffic lights’ that are used to control the movement of rail traffic. The trams have to use retractable steps to overcome the big gap between the 2.65 meter-wide trams and platforms which can handle 3 meter-wide trains. These steps also enable later models of the trams, whose floors are 570 millimeters above the ground, to work with both 380 and 760 millimeter-high platforms.

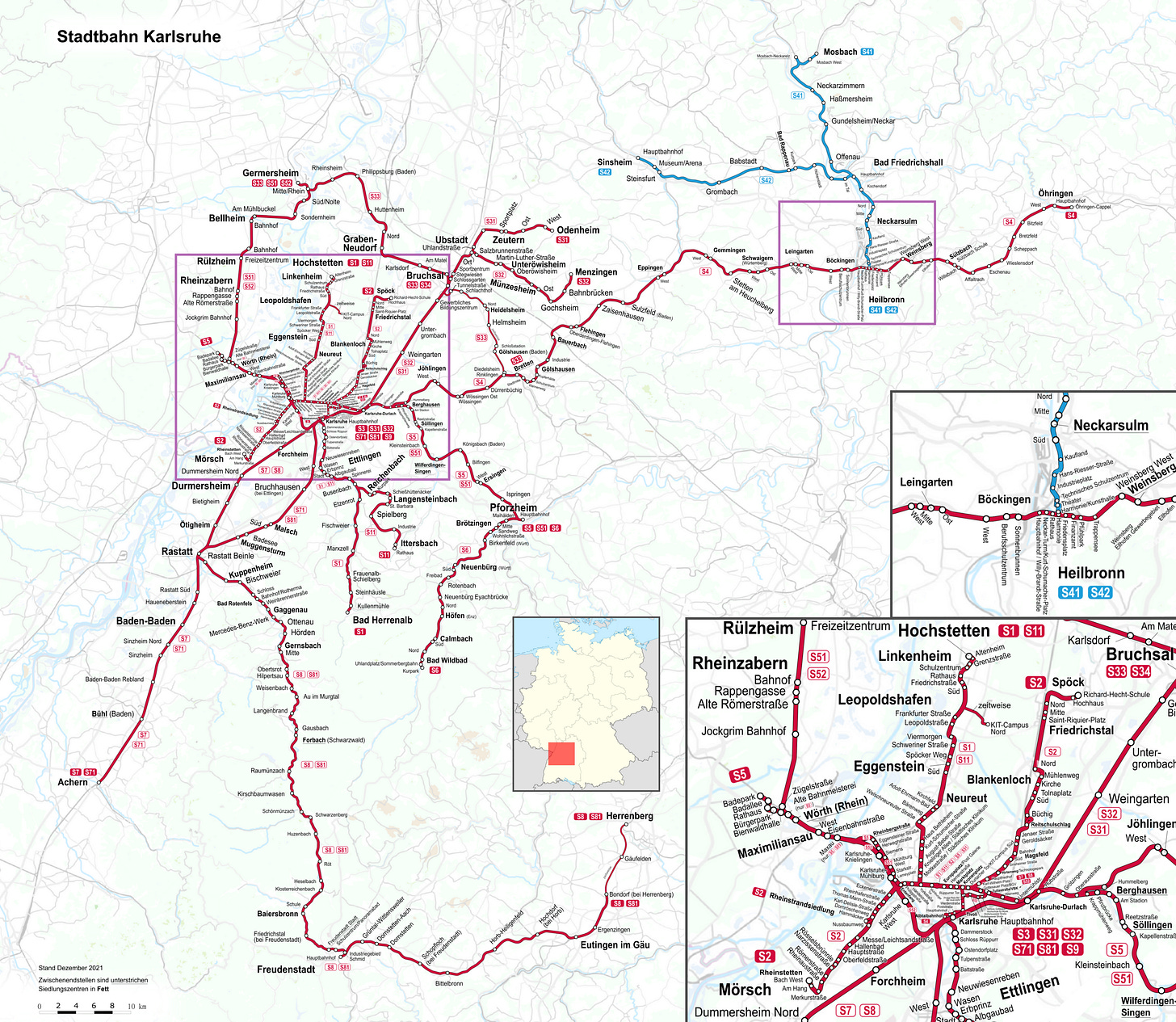

Overcoming these technical problems led to a much better network. Ridership of the Bretten line went up 400 percent after it was extended into the city center on tramlines, and the line now has 18,000 trips per day, up from 2,000 before the tram-train took over. Passenger numbers on the network doubled between 1985 and 1999, after several more lines had been added. The network today, which carries 170 million passengers per year, is over 660 kilometers long, longer than the combined length of Munich’s tram, metro and suburban railway networks.

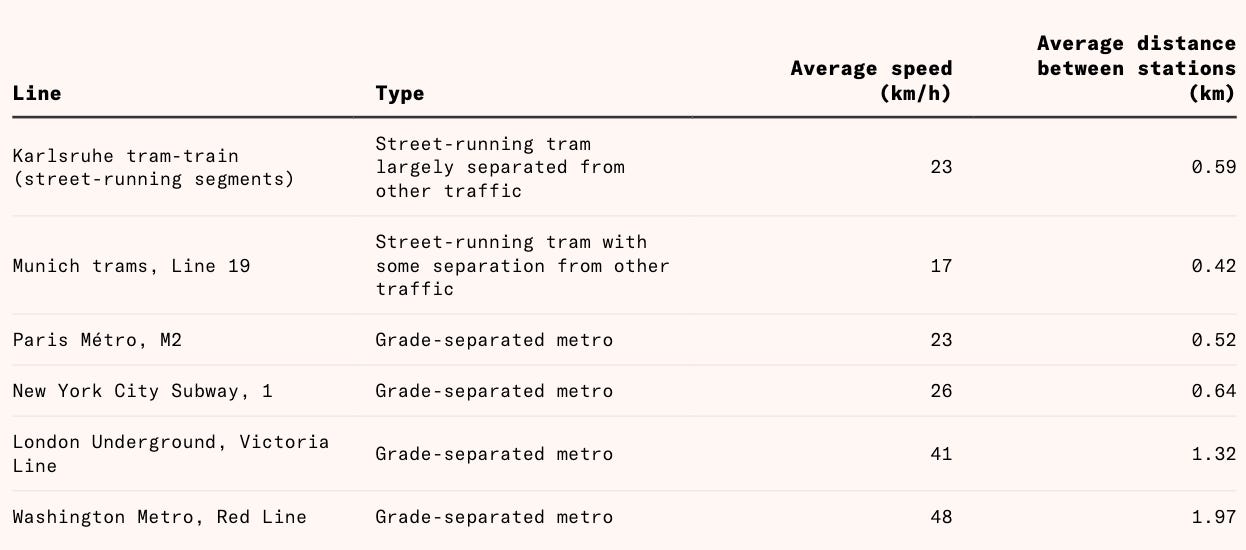

Tram-trains have trade-offs. Trams are slower than trains, because they have to share road space with cars, pedestrians and bicycles. Where possible, therefore, Karlsruhe runs the tram-trains down wide roads in the suburbs where trams can run in their own lanes, and it gives signal priority to trams at road intersections. Tram-trains manage speeds about the same as the wholly tunneled Paris Metro.

The fact that trams interact with other vehicles also means that they have to be short. The Munich S-Bahn has a maximum capacity of more than 50,000 passengers per hour per direction because of its 200-meter-long trains, similar to London’s Elizabeth Line. Manchester’s Metrolink, which runs 60-meter-long units, can transport 15,000 per hour on its busiest section, while owing to its lower frequency Karlsruhe’s 75-meter-long tram-trains, as long as trams can feasibly get without causing unbearable problems for other road users, carries only 8,800.

Other models of light rail

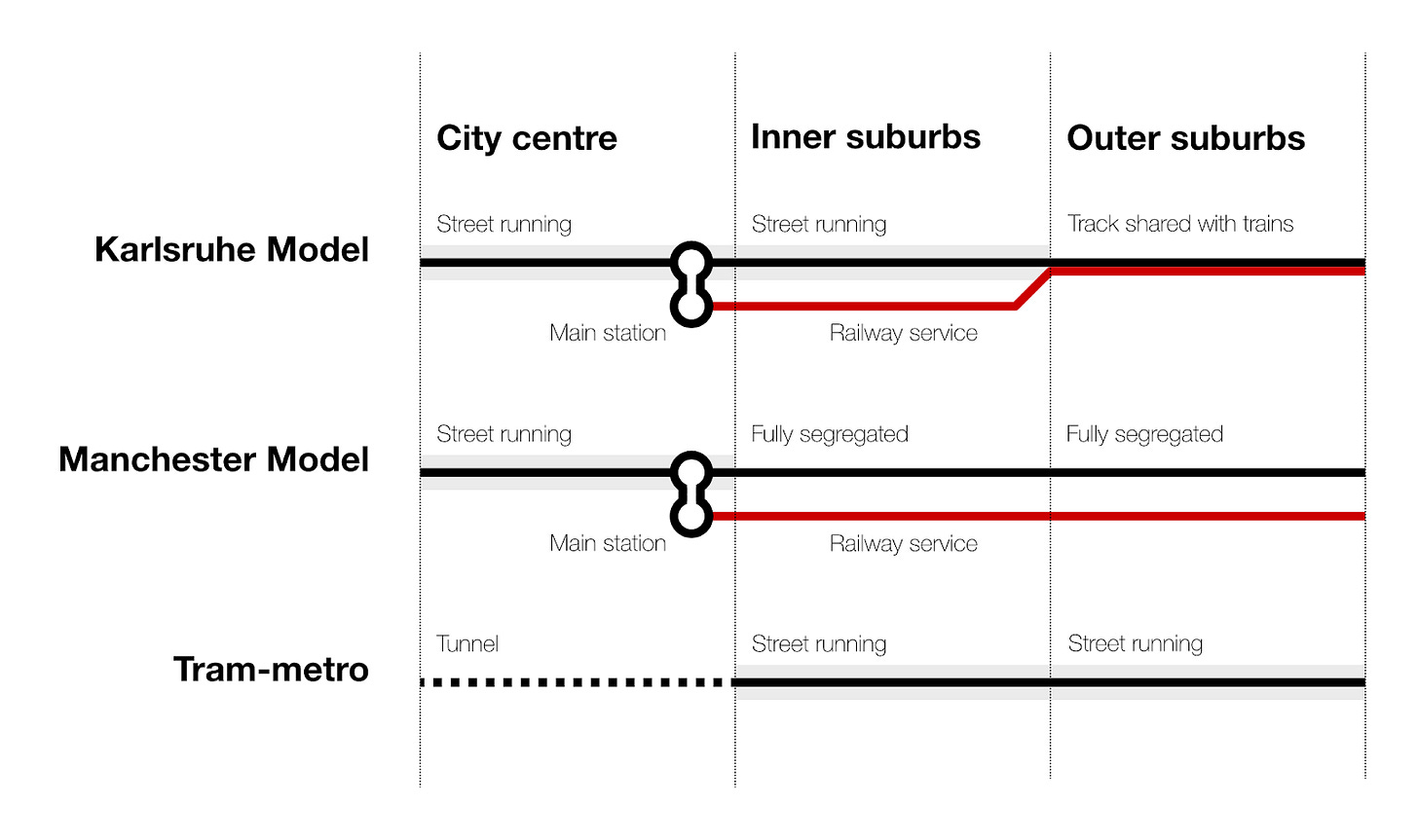

The Karlsruhe Model involves mixed traffic: the tram-train lines also carry longer-distance trains and some freight. This caps capacity and reliability.

For this reason, some bigger cities such as Manchester, Dublin, Melbourne and Rotterdam, have converted railway lines to tram lines, with no other form of traffic allowed, enabling more frequent services. This often means the railway line needs to be closed to be converted to tram standards: in Manchester, the commuter line to the southern suburb of Altrincham was closed for six months to enable the electrification to be converted to 1,500 volt direct current from the British standard of 25 kilovolts alternating current.

In Manchester, however, the trade-off was worth it. There was no other traffic on the Altrincham Line, and the city is three times as big as Karlsruhe, so needed a more frequent service on its tram-trains: the line now runs a tram every six minutes.

Another model is the ‘tram-metro’. This is common in medium-sized German cities like Düsseldorf. It involves trams that run on the streets in the suburbs of the city, and then go into a tunnel under the city center. Although this is more expensive than running on streets, tunneled trains are never held up by traffic in the center.

Karlsruhe has, in fact, now built a tunnel for its tram-trains. The ‘Kombilösung’, or ‘combined solution’, which was completed in 2021–2022, involved building two tunnels.

One of them was a 2.1 kilometer-long tunnel under the city center for the tram-trains, which enabled the main shopping street, the Kaiserstraße, to be fully pedestrianized, creating a three-way hybrid: a tram-train-metro. This would not have been justified with the ridership numbers of the 1990s, but by the 2020s passenger numbers had grown so much that it was viable and necessary to prevent the Kaiserstraße from being congested.

The purpose of the other tunnel was to put the city’s main east-west artery, a ten-lane road known as the Kriegsstraße, underground, and to build a boulevard on top where tram traffic can run uninterrupted by cars.

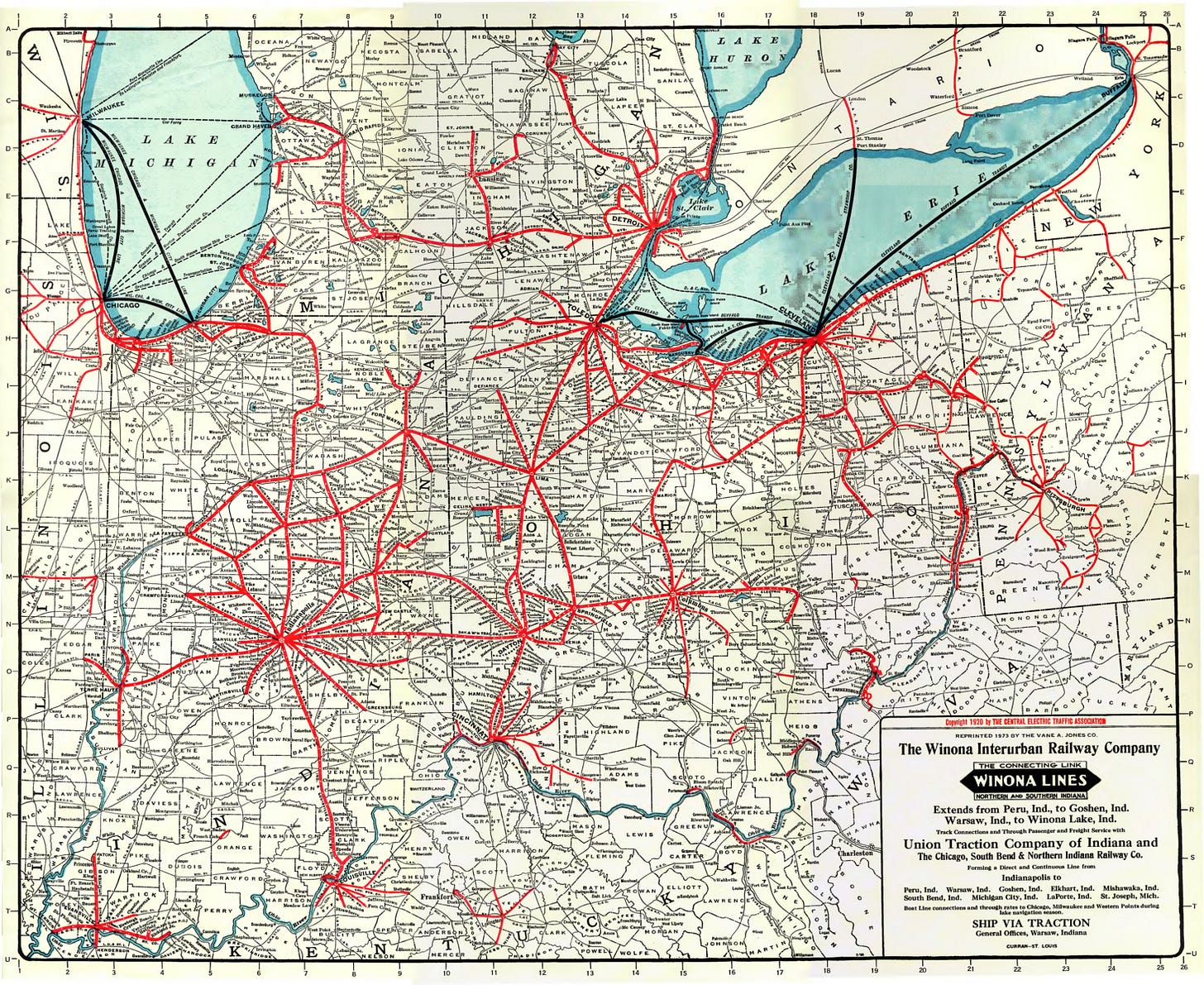

A final model of light rail worth mentioning is interurbans. Interurbans ran on streets within cities, while in suburbs and in rural areas they ran alongside roads or on dedicated rights-of-way. These systems were sometimes staggeringly expansive: at one point, it was possible to travel from Wisconsin to New York State exclusively by interurban. In the American Midwest, they were the main method of rail transport, outcompeting the commuter services offered by the American railroads. Although most of the interurban lines closed in the postwar period, a few of them are still there today: the South Shore Line still runs from Chicago to South Bend.

The case for tram-trains

Choosing between these different models of light rail is a trade off between cost, engineering difficulties, and the ability to reuse pre-existing infrastructure on the one hand, and capacity, speed and reliability on the other. But there is one specific advantage of tram-trains: their similarity in spirit to interurbans.

The key advantage of interurbans over ordinary suburban railway lines was their ability partially to solve the ‘last mile problem’. Railway stations are often awkwardly sited far away from town and city centers. Usually, this is for engineering reasons: railways are unable to navigate steep gradients, so the Victorian builders had to go where the land was flat, not where people wanted to go. Furthermore, railway lines were often optimized to link two big places together quickly, rather than adding connections to all of the smaller towns en route. Because they could travel on streets, however, interurbans could go anywhere within a town or city, with stations nearer to people’s origins and destinations.

Bringing back the interurbans would be prohibitively expensive. Even in Germany, where the average mile of new tramway costs just $32 million, a network as extensive as the motorways – 8,200 miles – would cost around $270 billion. In Britain, it would be more expensive still: tramways cost $118 million per mile, and in Australia, they come in at $165 million.

The Karlsruhe Model allows interurban-like service at much lower costs. In many cities, the suburban railway lines have already been built: they just need linking up to a tram network.

A concrete example of where tram-trains would be useful is Oxford, UK. Oxford is not big enough to justify a metro: there are only 260,000 people within ten kilometers of its center. The city’s main station is quite far from the center, like in Karlsruhe, and currently has little development around it. This means that a through-running network focused on Oxford station would fail to serve all the places people want to go to. A tram-train network, however, could enable people from the towns and cities surrounding Oxford to get directly into the center, plus direct service to the centers of the surrounding towns like Abingdon and Bicester, and possibly Reading.

Something similar could be said for many French cities. France has been undergoing a tramway renaissance: it has built 21 new tram systems since 2000. But, even though France has an extensive high-speed rail network, and excellent transit within urban areas, its suburban railway lines are operated infrequently outside Paris. For this reason, the country is planning to run its suburban trains through the center in 26 metropolitan regions. In smaller cities like Tours, this could be done by running trains onto the existing tram networks. The same goes for many of the smaller cities in the former Eastern Bloc, which often have extensive tram networks as well as suburban railway lines in need of upgrading.

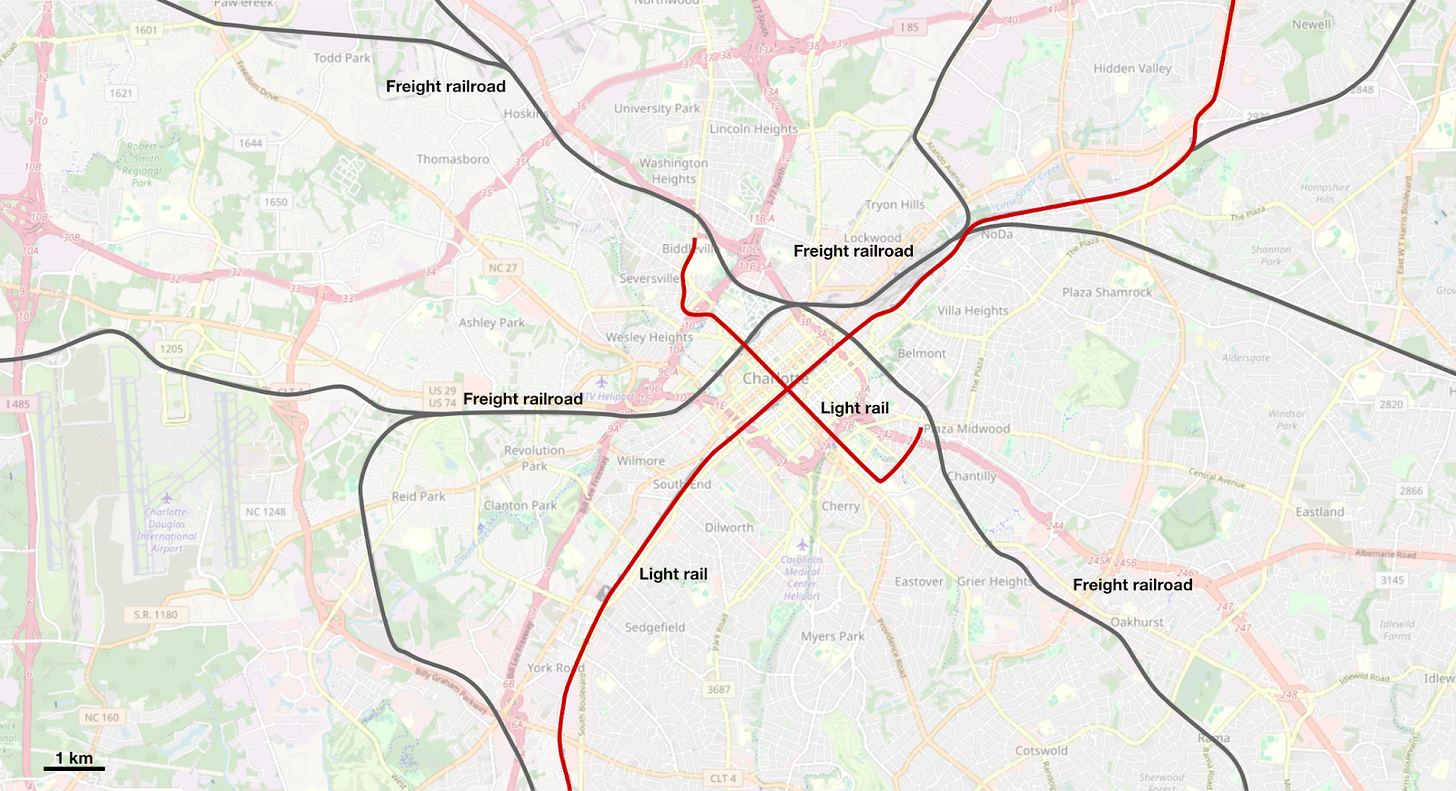

The biggest opportunity, however, is perhaps in North America. Take Charlotte, North Carolina. The American model of huge low-density suburbs means Charlotte only has 380,000 people within ten kilometers of its center, even though its urban area overall has 1.4 million people, similar to Munich’s. The low density of Charlotte means a transport network like Munich’s is not viable, but the city could take its pre-existing light rail network and join it up to the extensive network of railroad lines around the city that are currently used only for moving freight.

Tram-trains are not suitable everywhere. In big cities like Munich, through running needs to use a tunnel, for reasons of speed and capacity. In some smaller cities like Utrecht, then there is no need: the main station is close to the city center, which is compact enough that it can all be reached on foot. Utrecht has therefore implemented through running simply by running trains through the main station, without needing any more infrastructure. Other cities don’t have any wide streets in the center on which to run tram-trains. These need viaducts or tunnels, or need to demolish buildings to make space. Or they will have to do without.

But in Oxford, Tours and Charlotte none of these things are true. Bring on the tram-trains!

Benedict Springbett is a writer and Bar student based in London.

In the US, not one light rail system operates in the black. Also, freight rails are operated under the DoT and prioritized for mile-long freight trains, not passenger ones.

This is what Philadelphia's Trolley system does. It's in need of a lot of TLC but functions like this to connect the western part of the city to Center City and the heavy rail system.