What did Henry George think about cities?

Solving the terrible urban conditions of the 1800s by abolishing cities

Stripe Press is hosting one of its legendary pop-ups in Paris on 23rd May: register to come. We (Works in Progress) are hosting drinks that same evening: come hang out with us.

Our researcher and staff writer Samuel Watling explains why Marx, Engels, Owen, and especially Henry George wanted to abolish the city, and spread people evenly across the countryside. Don’t miss his piece explaining how planning restrictions are the modern-day equivalent of the Corn Laws.

The urban question

The Industrial Revolution combined rapid population growth with the development of an urban society. Research by the British demographic historian Anthony Wrigley suggests that in 1600 just 6.1 percent of England’s population of four million lived in towns with a population of over 10,000 or more, less than the western European average of 8.0 per cent. By the time of the 1851 census England’s population had more than quadrupled, but its total urban population went up by a factor of 25, making it the world’s first primarily urban society, with 51 percent of the population living in towns and cities.

Urbanization was propelled by industrial development. Factories were set up either in or near towns. Towns offered access to a labor supply and services such as finance and transport. The latter was key as factories had to import food and fuel. The slow and expensive nature of inland transport before the steam engine (despite the enormous improvements of the canals and the turnpikes) meant major industries had to be directly sited near power sources such as coal mines (Birmingham, Nottingham), existing ports (London, Liverpool), or both (Glasgow, Newcastle).

From 1700 to 1850 millions migrated to these well situated areas, which were small towns by modern standards, increasing their populations by factors of up to fifty. This transformed them out of all recognition into bustling metropolises. Birmingham, which had an estimated 7,000 inhabitants in 1700, had grown to nearly 300,000 by the 1851 census. Over the same time period Liverpool grew from 6,000 to 375,000 and Glasgow from 14,000 to 350,000.

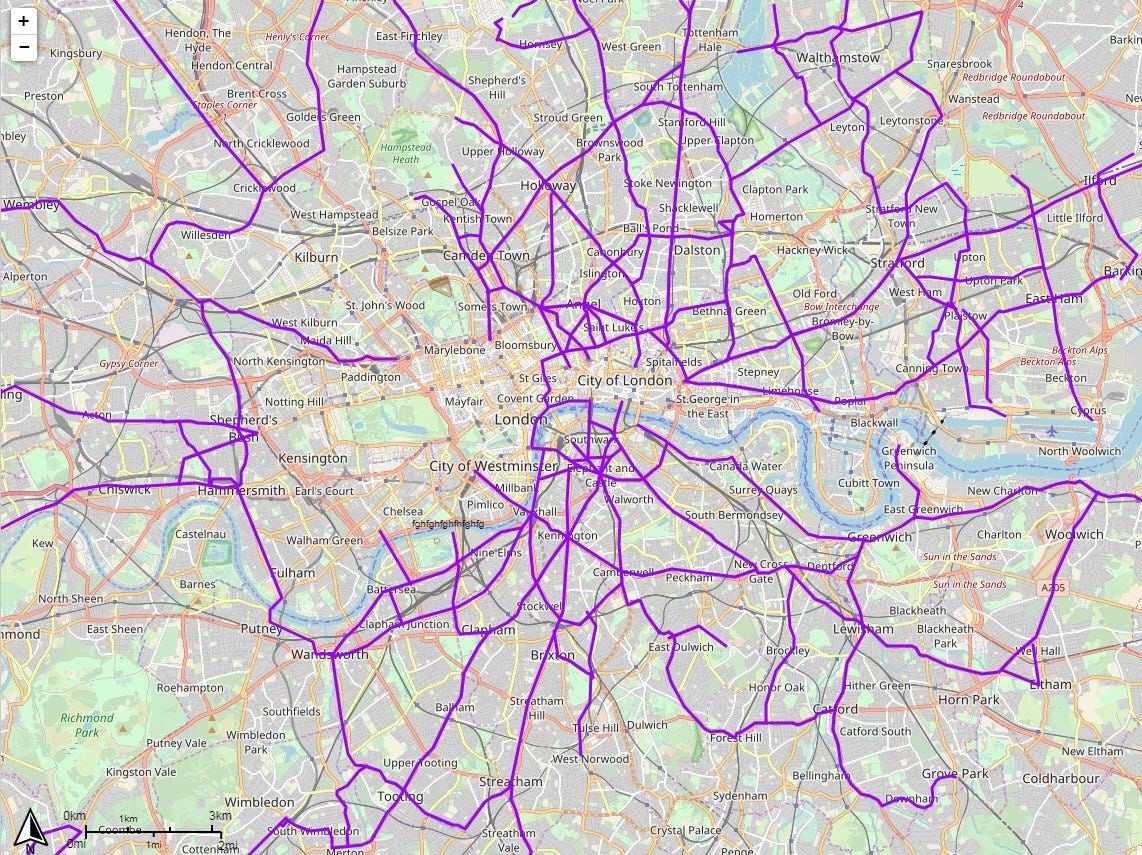

Above all, London grew to be the world’s biggest city in the early 1800s, with just over one million people. By the end of that century it had a population of around seven million. Housing those extra millions required dramatic urban expansion. In 1807, London stretched from Hyde Park to Limehouse; it was difficult to walk more than five miles (eight kilometers) without leaving the city. By 1913 it extended at least from Ealing to Leamouth – some 30 miles (50 kilometers) – and covered an area many times larger.

This clustering in cities had further beneficial effects. Specific industries clustering in cities (cotton in Manchester, iron in Birmingham) meant that industry now had access to a pool of skilled workers and industry-specific knowledge. This drove growth through specialization (such as in Adam Smith's famous pin factory) and technological innovation.

Yet until the 1830s this progress was not enough to guarantee increases in the standard of living for the majority of the population. The famous mechanized industries of cotton and iron grew rapidly, but from a small base. Much of the urban workers were still employed in low productivity craft manufacturing or services.

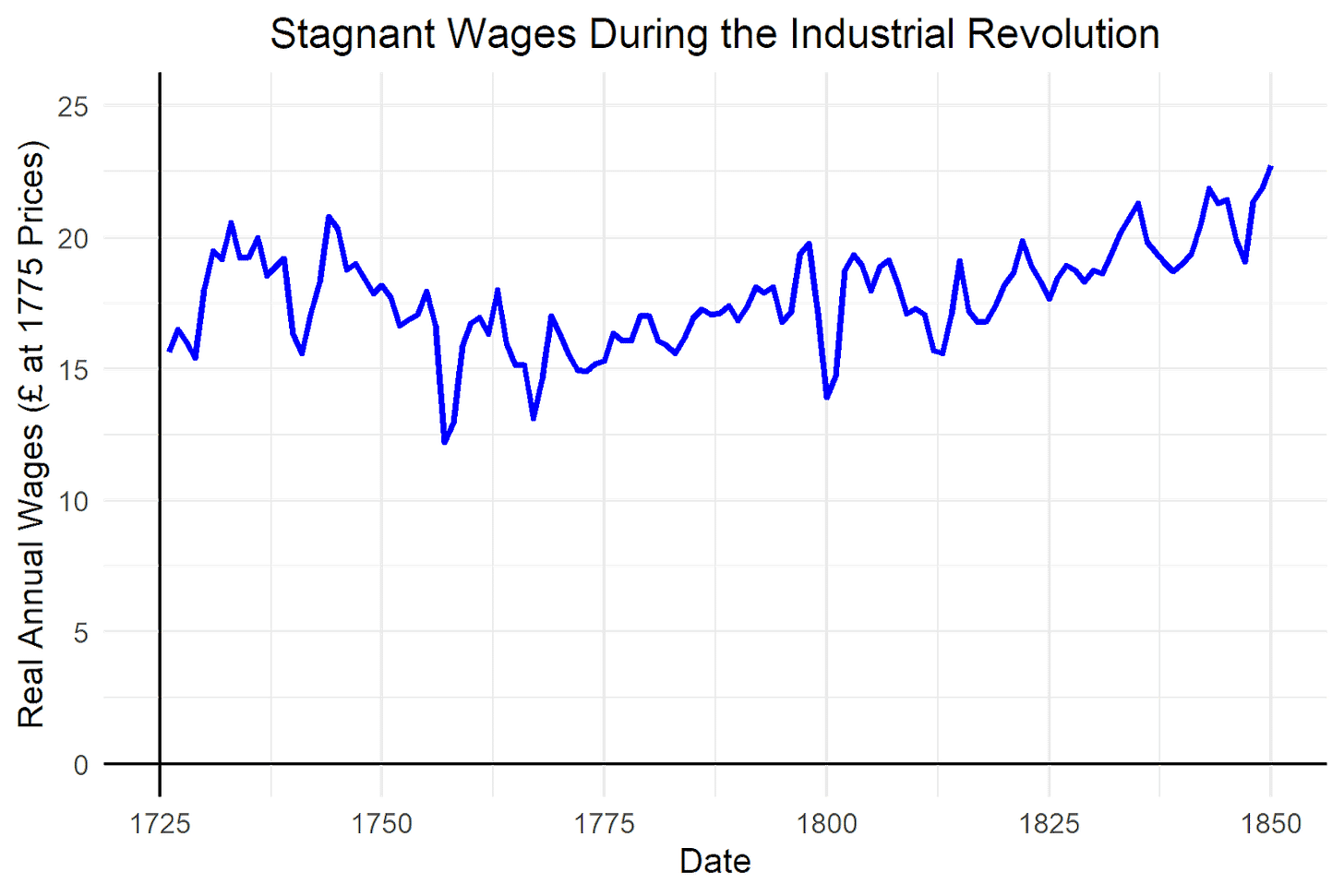

Slow economic growth combined with a population explosion meant that per-capita improvements in GDP were low. Estimates by Nicholas Crafts suggested per capita growth averaged 0.17 percent between 1760 and 1800 and 0.52 percent from 1800 to 1830. From the mid 1750s to 1830 wages for most laborers were static.

Although by today’s standards this would be disappointing, by historical standards this was an unprecedented achievement: in pre-industrial societies a rapid population increase would lead to a collapse in wages, as occurred in a host of contemporary countries from Ireland to China.

Yet unsurprisingly, most people did not view their circumstances in this way. Despite clear technological progress the new urban workforce toiled 60 hour weeks for real wages that were no higher than their grandparents. This was made worse by the strong disamenities of the cities of that time.

Cities and mortality

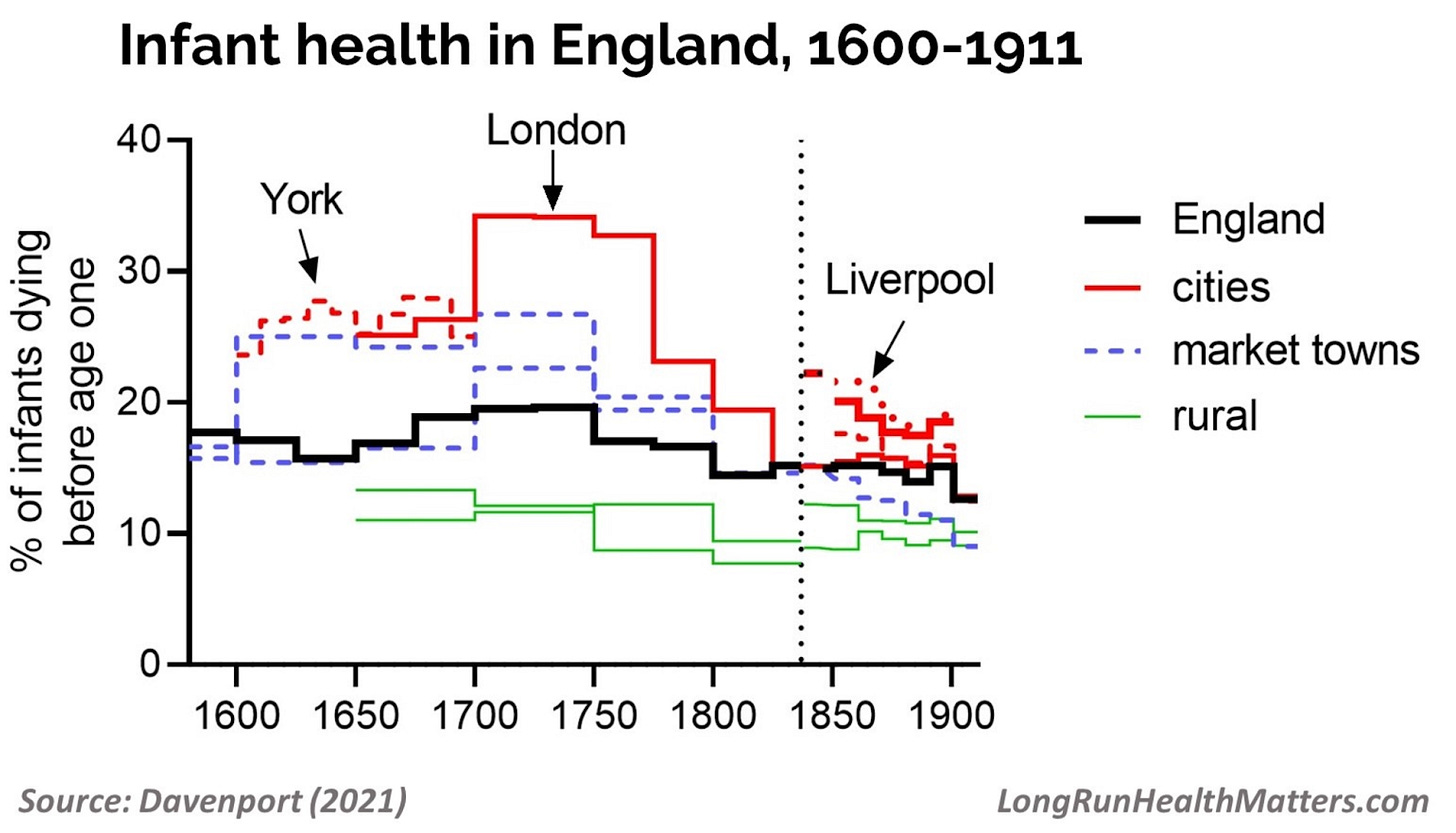

Throughout most of human history cities were population sinks. High population densities combined with inadequate sanitation systems meant that diseases were common and spread quickly. Outbreaks of plague and smallpox meant that seventeenth and eighteenth centuries meant that in seventeenth century London 30 percent to 40 percent of children died before the age of five, resulting in an average life expectancy of around 20. By contrast in rural areas the mortality rate was often under ten percent. The resulting high death rates meant that before 1800 the urban death rate was higher than the birth rate, meaning that cities were dependent on rural migration to maintain their population.

However by 1800 public health policies had improved sufficiently through smallpox vaccinations and plague quarantines to increase London's life expectancy by one half between 1750 to 1811. A life expectancy of 30 may be awful by modern standards, but it was sufficient to make urban births higher than deaths, though rural life expectancies were consistently around ten years higher.

After 1830 this nascent progress reversed. Repeated outbreaks of an aggressive strain of scarlet fever increased infant mortality in both urban and rural areas. The cities faced added problems. London's lack of formalized sewers meant untreated sewage was dumped directly into the Thames, which was also its main source of drinking water. The result was repeated cholera epidemics, the two worst of which claimed over 10,000 lives in 1848-9 and 1853-4.

Cities were also impacted by events outside their control. In the 1840s a large wave of impoverished and sick refugees from the Irish Great Famine fled to cities on England’s west coast such as Liverpool and Manchester. Whatever medical services and public health infrastructure that existed were overwhelmed. By 1850 life expectancy in these areas had fallen back to under 30.

Intellectuals and cities

To an early nineteenth century observer the benefits that the new industrial cities conferred upon urban workers appeared non-existent. Workers earned similar wages to before the Industrial Revolution while simultaneously living in unhealthy areas which shortened their life expectancy.

It is therefore unsurprising that much contemporary thought was anti-urban. This intellectual trend was pioneered by the early socialists. Robert Owen, the leading socialist thinker in the English speaking world in the first half of the 19th century, proposed replacing modern cities with individual communities of 1,200 people on large estates of between 400 and 600 hectares (1.5 to 2.3 square miles). This idea was accepted by the Communists Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, who demanded the ‘gradual abolition of all the distinction between town and country by a more equable distribution of the populace over the country’ in their 1848 Communist Manifesto.

Following this the conditions of the urban working class began to improve. With the development of the railways in 1830 transportation costs were reduced sufficiently to make industrial production viable nationwide. Strong economic growth began – around the modern rate of two percent per capita – and this was enough to cause continued wage growth across the country.

From 1850 public health and urban life expectancy finally began to improve. Part of this was due to the Scarlet Fever epidemic and Irish famine both ending. However, belated government action helped as well. The British parliament finally agreed to fund an adequate sewage system for London in 1858. This was not due to concern over cholera epidemics but rather that the Thames had become so inundated with sewage its sheer stench disrupted parliamentary proceedings.

This was replicated across the country when the 1875 Public Health Act finally made it a duty upon all local governments to provide clean water and adequate sewer systems. With these reforms urban life expectancy finally began to converge to rural levels for the first time in recorded history.

The other urban problem: the housing question

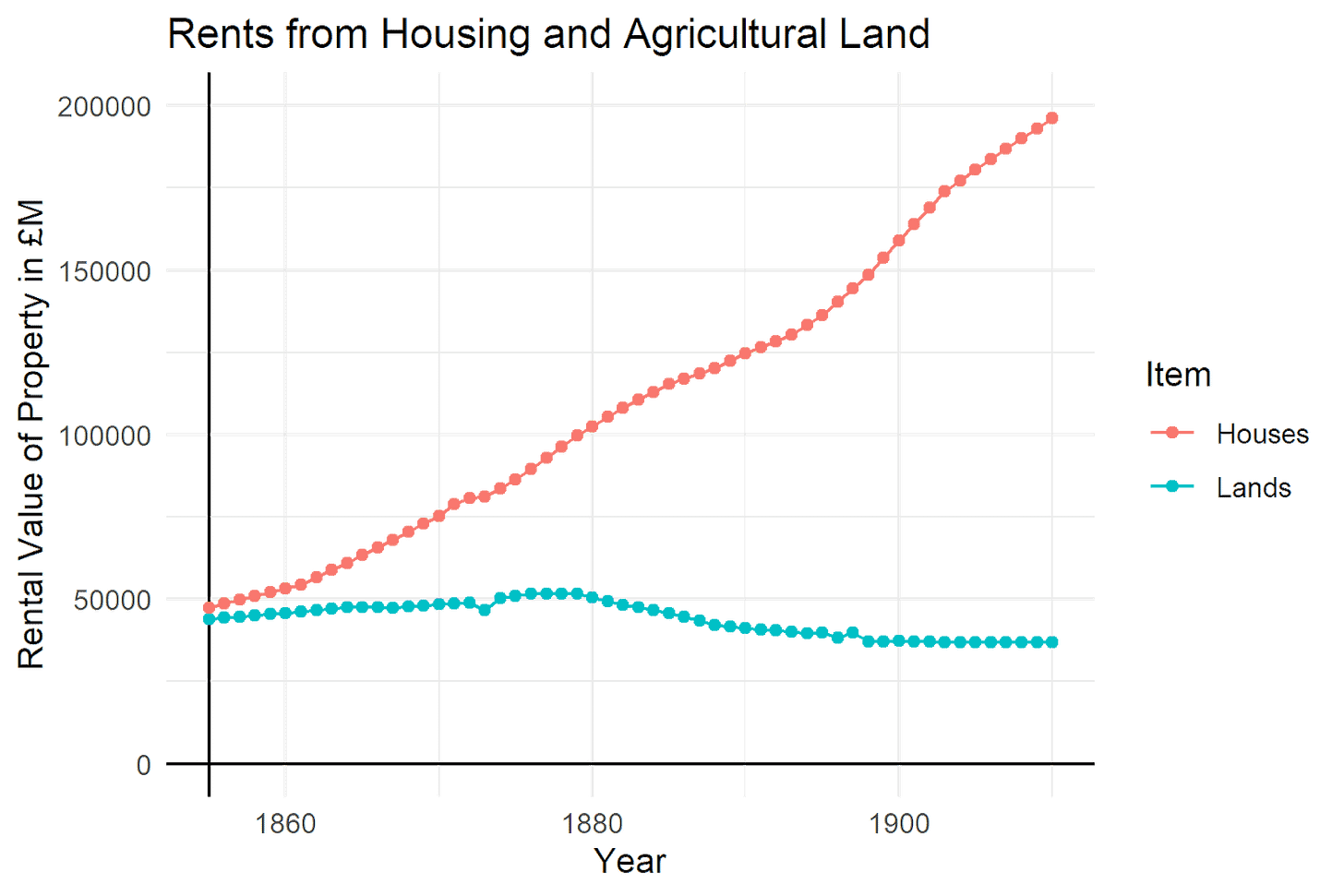

Although cities had begun to stop killing people, not all of their problems were solved. Poverty and overcrowding were rife. These problems only grew in political importance as urbanization continued during the last half the 19th century. By 1911 the urban population comprised 79 percent of England’s total. Total rents from houses were nearly equal to those from agricultural land in 1855, but had increased to more than five times them by 1910.

The continuing economic growth of cities produced tangible benefits but these were not evenly shared.

By the 19th century, all the major British cities were too large to expand with extra pedestrian suburbs. London was the most extreme example: commuters to London’s historic heart and financial center – the City – already walked an hour or so from West London suburbs like Belgravia, Pimlico, and Bloomsbury. But similar was increasingly true of other large cities such as Manchester and Birmingham, which were both approximately 2.5 miles across in 1900.

The marginal cost of adding new housing was high. Cities were already at their maximum practical height – roughly six storeys before the invention of the lift and the steel frame in the 1880s. And while some neighborhoods expanded through the horse-drawn omnibus and tram, congestion was terrible, meaning that it took one and a half hours to travel five miles in central London. Railways were the only solution, but building new networks inside now established cities required large scale tunneling, which had to be excavated manually using pickaxes. As a result they were expensive to build and the relatively few lines that were viable were immediately overcrowded.

When a city’s economic fortunes improved, this created more jobs and higher wages there. Workers would attempt to migrate there. This increased demand for housing. Since cities could only be expanded by building new infrastructure, owners of existing properties or land in the center earned a windfall as their property was now more scarce and valuable. Their land was only imperfectly substitutable with the less accessible land at the edge of the city which needed significant investment in capital to be viable for development. This meant they could charge higher rents than the construction cost would imply.

In south London, rents averaged one-third of working class budgets. Compare this to Donald Feinstein's estimates of around 10 to 15 per cent in primarily non-urban areas in the rest of the country in the early 19th century. High rents were coupled with strict terms. Landlords could evict tenants with one week's notice if a payment was missed which, given the precarious nature of much working-class employment, was a real threat to many families.

The 1875 Public Health Act gave Local Authorities power to impose byelaws regulating new construction, while the 1875 Cross Act gave those bodies the powers to demolish existing housing that violated health guidelines and minimum space standards. However, against the Act’s initial sponsor’s (William Torrens) explicit wishes, the local authority had no obligation to resettle those displaced. The result was social cleansing. As the 1885 Royal Commission on the Housing of the Working classes put it:

(Demolitions) have been accompanied by the severest hardship to the very poor, increasing overcrowding and the difficulty of obtaining accommodation, and sending rents up accordingly.

The anti-urban utopia

The continuation of urban poverty meant that the demands for the abolition of cities were still popular amongst progressive intellectuals. Engels still explicitly endorsed the proposals of Owen and repeated the demand to break up urban areas in his 1872 pamphlet The Housing Question.

The housing question can only be solved when society has been sufficiently transformed for a start to be made towards abolishing the antithesis between town and country … The modern big cities, however, will be abolished only by the abolition of the capitalist mode of production.

This view was not just confined to the left. The leading liberal economist Alfred Marshall proposed deporting London's ‘surplus labor’ and decanting them into distant ‘work colonies’.

However in the late Victorian age the most influential of anti-urban thinkers was Henry George. This is a great irony given that most of his followers today, who believe that taxing land will intensify its use by forcing owners to make the best use of it. Yet there was little place for cities in either George’s theory and proposed utopia. He made this clear in his most famous book Progress and Poverty, which sold several million copies, making it one of the best selling books of the era. His view, contrary to that of most of his current day disciples who believe a land value tax would encourage density, was that it would primarily obliterate most economic incentive for urbanization.

George denied the conventional explanation for high urban land prices and land rents, that cities always contained inherent advantages on production due to agglomeration effects and that land was only partially substitutable due diminishing returns on land and capital.

It is not the growth of the city that develops the country, but the development of the country that makes the city grow.

Instead, cities existed primarily due to irrational land speculation that meant that the laborers were unable to buy a smallholding and farm it and were therefore forced to migrate to the cities in search of work from the landed elite. This was, in George’s view, uneconomic because it resulted in the ‘exhaustive cultivation of large, sparsely populated areas’ which ‘results in a literal draining into the sea of the elements of fertility’ through the sewage system and was therefore environmentally unsustainable.

Through this logic he declared that all economists had been wrong and in fact the entire, rather than marginal, value of all land was an economic rent siphoned off from the productive forces of labor. He claimed that, as all production was derived from human labor, any immediate productive advantages from any location or available capital were largely irrelevant.

Since all land value was expropriation of human production, the solution was to tax all land income at 100 percent which would destroy the value of land and make it free to anyone who wished to use it. Importantly, this would impact urban areas the most.

The taxation of land values would fall with greatest weight, not upon the agricultural districts, where land values are comparatively small, but upon the towns and cities where land values are high.

The liquidation of all rent would also remove any differential in the price of land between areas. This would destroy the pressure for greater density that came with higher land prices, ending any economic incentive for further urbanization, reducing the urban population.

The destruction of speculative land values would tend to diffuse population where it is too dense and to concentrate it where it is too sparse. to substitute for the tenement house homes surrounded by gardens, and to fully settle agricultural districts.

Much of the population would then live in agricultural villages, which would fulfill all ‘conveniences, and amusements, the educational facilities, and the social and intellectual opportunities that come with the closer contact of man with man.’ This idyllic lifestyle would mean neither they nor their children would ‘be so impelled to seek the excitement of a city’.

For George his proposed Land Value Tax was not just an economic remedy. It would return man to nature and end all inequality and social division. In doing so it would disprove all pessimistic writings about human nature and so redeem mankind’s faith in god.

Thus the nightmare which is banishing from the modern world the belief in a future life is destroyed.

The land value tax really would solve everything.

Solving the urban question in practice

The mix of Christian providentialism, a non-socialist redistributive philosophy and an excuse to tax landowners was catnip to left wing parties around the world, including the ‘radicals’ of England’s Liberal Party. Under another George, David Lloyd, the Liberal campaign for Land Value Taxation succeeded, but ultimately its land tax was a failure.

Yet ironically as the proposals for a land tax gained momentum the issues of urban rents began to attenuate. Electric trams made it much cheaper to add new neighborhoods within commuting distance of jobs. And electrifying London’s tubes and suburban railways compounded this.

Both of these reduced house prices, and reduced the windfall premium to well-located land (and its owners) that otherwise came from economic improvements, since they expanded the supply of land that could (imperfectly) substitute for this land. This continued after the First World War with rail electrification across the country and the foundation of motorized bus networks allowing expansion outwards. New technologies such as lifts and steel frames made it cheaper to build up. Britain had the largest housing boom in its history. The old ‘urban problem’ of inadequate housing appeared to be near a solution.

Ironically, it was this success that finally gave anti-urban ideas their political base. The expansion of cities caused residents on the urban fringe to lobby for restrictions on urban expansion. The UK’s resulting Town and Country Planning Act, imposed in 1947, took the anti-urban ideas of the Victorians and put them into practice. The ‘unearned increment’ of land values would be expropriated by the state, in part to deliberately destroy the incentives for further urbanization. Urban growth would then be stifled and dispersed into towns. Just as Henry George wanted.