Notes on Progress are pieces that are a bit too short to run on Works in Progress. You can opt out of Notes here.

Between 1934 and 1939, at least 56,000 flats were built privately in London in over 300 blocks, the most significant period of such development before the 21st century. This boom started suddenly, after decades in which few private flats were constructed, and ended with the outbreak of war. It is almost entirely written out of history books including specialist housing tomes – as it was so at odds with the dominant planning ethos of the time, influenced as it was by the Garden City movement.

High density urban settings were seen at the time as synonymous with poor living conditions and the house, garden and town were emphasised as optimal. This was, after all, the era of the suburb and mass owner-occupation, when more than 300,000 mostly semi-detached homes were built speculatively each year on the edge of prosperous British cities, particularly London and in the Midlands.

Unlike the late Victorian mansion blocks – which had overwhelmingly been aimed at the upper-middle and upper classes and built in what are now the boroughs of Westminster, Kensington & Chelsea and Camden – these 1930s flats were more numerous, if more spread out. They appeared in a far wider range of areas and were designed for a much broader set of budgets, with almost 17,000 of them in Outer London. Private ‘luxury’ flats also appeared in the main cities outside London for the first time, notably in then-affluent Birmingham. As owning apartments individually was almost unknown at this time outside of Scotland, they were usually held by the investors that had financed them and rented out.

The rise of the flat

The purpose-built flat (historically ‘tenement’ if working class and ‘apartment’ if upmarket) has a short history in England. Although model tenements aimed at manual workers appeared slightly earlier – and in significant numbers in Merseyside and London – it was not until the mid-19th century that the first privately built blocks of flats were built in the capital, firstly around Victoria Street in Westminster and then further afield. The apartment was, by then, already well-established as an aspirational housing form in most cities on the continent, as well as in Scotland. Only the Low Countries displayed a similar aversion to this ‘horizontal living’.

The earliest examples in Edinburgh predate those in London by over two centuries: there are several still surviving in the Old Town which date from the 17th century. A geographically constrained site, a more unruly countryside, and a land system which enforced an in perpetuity charge to the original landowner (the ‘feu’) encouraged higher, more dense development. Once these patterns were established in the Scottish capital, they became the norm in other Scottish cities as they developed, particularly as Scottish law from an early date enabled the purchase of parts of buildings, a notable difference with south of the border. The tenement became the urban housing form in Scotland, with similar facades hiding both grand middle-class apartments and overcrowded working-class rooms; there was much less distinction of housing by appearance. (As late as 1966, some 8 percent of all dwellings in England & Wales had been originally designed to share a common building; in Scotland the figure was 51 percent. Indeed, when Scotland did suburbanise, bungalows were unusually popular, reflecting the custom of one-storey living).

In contrast, English cities mostly lost their defensive function much earlier and suburbs with houses sprang up from the 18th century onwards. Many of these were developed on the great landed estates, such as Grosvenor and Bedford, which were often constrained in their ability to sell land by ‘strict settlement’. This aimed to prevent individual benefactors from selling land, to ensure the estate could be passed on to subsequent generations intact. This meant development proceeded by granting builders such as Thomas Cubitt a ‘building lease’ for a set period of time, after which the ownership would revert to the estate.

This alone favoured individual dwellings, something reinforced by the 1774 Building Act, which laid out specific dimensions for houses in London and was responsible in many ways for the classic Georgian terrace and square – although the estates themselves often also enacted strict controls on design and materials. The act was copied in other cities such as Liverpool, Newcastle and Bristol, where extensive terraces on similar lines still exist.

The Victorians hated the ‘black act’ as they called it; they deemed the resulting uniformity horrific. However, similar processes and models also applied to working class areas, meaning similar, if much more modest terraced dwellings arose, even if they quickly became multi-occupied slums. Indeed, the inflexibility of housing types combined with varying degrees of overcrowding may explain why later reformers were so obsessed with reducing density. (There is one exception to the terraced rule: in the North East, perhaps due to the proximity to Scotland, the ‘Tyneside flat’ and its variants emerged – effectively two apartments on top of each other within what looks from a distance like a conventional terrace. Some similar flats were built in the ‘artisan’ suburbs of North East London.)

Of course, some of these houses were in practice multi-occupied as ‘rooms’, but they were not designed for this. It is unclear what led to the first private purpose-built apartments being built in London. Some point to the invention of the lift, others to the influence of Hausmann’s redesigned Paris, others to the growth of London which made more cost-effective central residences desirable. High land values may have been the overriding factor. The first ‘mansion block’ was built in 1853 on Victoria Street, which had been newly laid out west of the Houses of Parliament, partly to clear the notorious Devil’s Acre slum that fell under the morning shadow of the Houses of Parliament and Westminster Cathedral. This had resulted in a number of plots becoming available for building. According to The Builder, the first was built by one Mr McKenzie as ‘his own invention and the idea we believe originated with him.’

Others followed. By the late 1870s and 1880s serious architects such as Norman Shaw and Ernest George & Peto became involved, often at the behest of the Great Estates as leases on the original Georgian town houses fell in. In these instances there was often a degree of masterplanning and design control that produced some elegant new neighbourhoods. During these years, there were very few private houses built in Central London as mansion blocks sprung up on every available suitable plot in a semicircle, from Hampstead and Maida Vale to Battersea and Clapham.

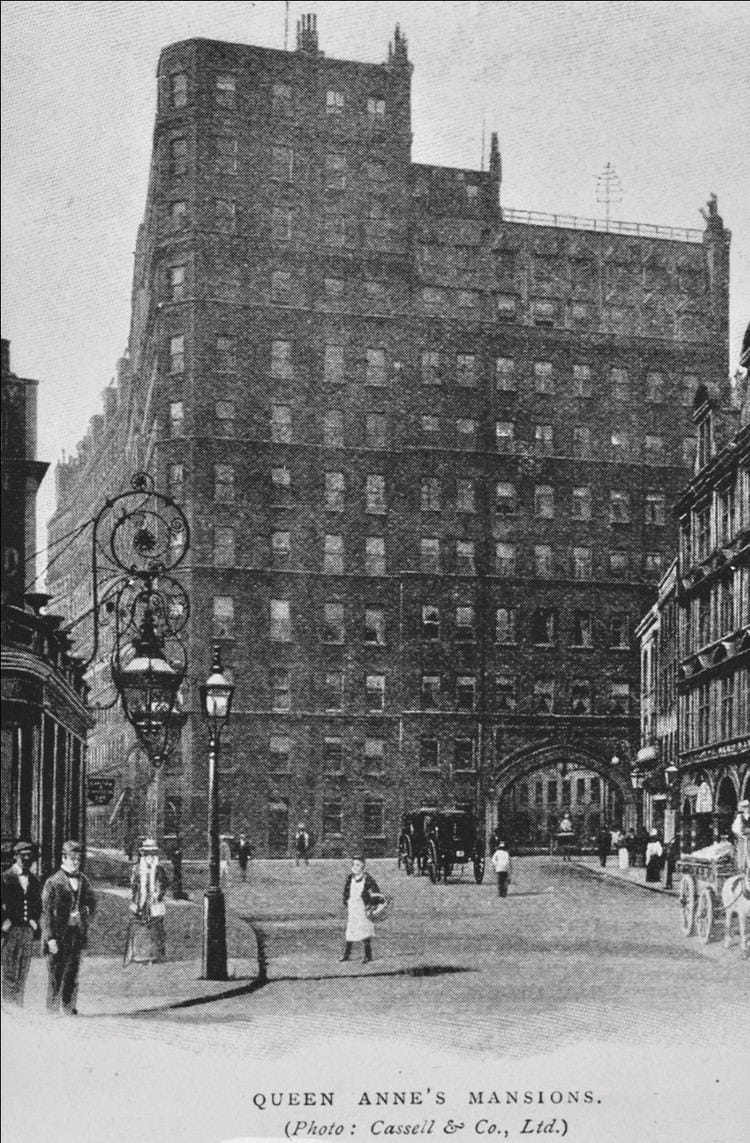

Their arrival in England was not without controversy; some saw them as foreign imports, dangerous both socially and physically. After the 14-storey Queen Anne’s Mansions development near St James’s Park in the early 1870s, the London County Council restricted building heights to 90 and then 80 feet (about eight storeys), a restriction that appears to have held sway until after the Second World War. There are suggestions that this was due to complaints from Queen Victoria herself, as it overshadowed the park, but the stated reasons were safety-related: the maximum height a fire hose could drench from the ground and the greater potential for collapses. It seems just as likely that the underlying reason was widespread prejudice against ‘French flats’ and tall buildings in a city where townhouse living was the accepted norm. (To be fair, the properties were also marketed with descriptions of French and Scottish life to demonstrate the advantages of apartments).

The late Victorian vogue for London flats was significant – it produced over 40,000 at a rate of 5,000 to 10,000 per year, and established the ‘luxury flat’ as an aspirational British housing type, setting the scene for the inter-war boom. But it was short lived. There were hardly any more flats built between the turn of the century and the mid-1930s. The traditional source of investment in urban housing, the private landlord, had been kneecapped by the introduction and maintenance of wartime rent controls. The combination of high inflation and a sharp economic downturn after the First World War – and attempts to maintain the gold standard – resulted in a sharp increase in construction costs and Bank of England base rates of 6 percent by 1929.

These cumulative shocks led to a sharp reduction in private building activity and rented flats did not look like good investment options as returns from bonds soared against the background of rent controls. This was partly counterbalanced by an increase in social housing built in flats – first Peabody-style ‘artisan’ blocks and then local authority dwellings. Meanwhile, transportation improvements such as motorised buses and electrified trains pulled demand away from urban settings. Middle class families moved into plush new houses designed for smaller households in Arts-and-Crafts suburbs such as Bedford Park rather than renting in the city.

The boom begins

After Britain left the gold standard in 1931, interest rates fell from 6 to 2 percent. This, coupled with the relaxation of rent controls on new properties in 1931 and falling returns from shares and bonds made rented property look like a good investment for private builders. Materials became much cheaper over the course of the decade. For example, the cost of a three-bedroom local authority house fell from around £510 in 1925-6 to £361 in 1934 – a fall of 29 percent. This all enabled taller, higher quality buildings, meaning the image of flats could improve again, with a new emphasis on their convenience and utility – a romantic view of urbanism influenced by Art Deco imagery from 1920s New York or Chicago.

Meanwhile, office and service employment had surged in urban areas during the interwar years, leading to an increasing number of young single people and couples working in Central London. They had also become significantly more affluent. Real wages nationally rose by over 26 percent between 1922-4 and 1935-6, with skilled manual workers and junior white collar workers seeing the fastest gains (apart from the most senior professionals). At the other end of the market there was a stratum of wealthy families who, a few decades previously, would have aspired to living in a centrally located townhouse or perhaps a larger pile slightly further out.

Rising staff costs, and innovations in heating and insulation, must have made this drafty lifestyle look uneconomic and uncomfortable compared with the amenities and services advertised in the new more upmarket blocks. Many flats of all types were actually built on the sites of unfeasibly large Georgian or Victorian homes – easily done in the interwar period when, except for financial contributions, safety regulations, any historic covenants and the aforementioned height limit, you could do whatever you liked with your property.

There is another reason why the boom happened at the end of the decade. The sheer scale of housing development in the home counties was raising some questions: buyers and developers were beginning to feel that the market might be saturated and on the verge of a crash. Builders’ pooling approach to mortgages, which reduced the need for a deposit from 25 percent to 5 percent of purchase price, was coming under scrutiny. In the early days of this system, builders would deposit 20 percent of the purchase price of each house with the building society; later, their bank would deposit an equivalent amount with the building society using the land value as security. The problem was that this practice was pushing up land prices (compared to if customers had required a 25 percent deposit) and the valuation was in any case provided by the builder. It would lead to scandals by the end of the decade. This bad publicity – and deteriorating imagery and reputation amid parallel accusations of ‘jerrybuilding’ – was perhaps putting some people off buying these detached and semi-detached homes in new suburbs.

The largest of the flat developers was the Bell Property Trust, set up by the two entrepreneurs Anthony Somers, who had made his money out of the hire purchase industry, and Reginald Toms, a dealer in army surplus equipment. They built, among several others, the vast Park West complex at Marble Arch, the 146-flat Highlands Heath in Putney (which featured ‘Art Deco interiors designed by Liberty of London’) and the remarkable Ealing Village, built in a Dutch-Colonial-Baroque style with a clubhouse and swimming pool, which attempted unsuccessfully to attract stars filming at the nearby studios.

Another important firm was Beaumont Properties, owned by future Conservative MP Cyril Black, a strict Baptist who would go on to campaign against the liberalisation of abortion, gambling, pornography and homosexuality in the 1960s. (Somewhat ironically, his grandson is the founder of Betfair.) Most developers were funded by insurance funds – during the Victorian period many rented homes were simply built using personal savings – and many blocks ended up in the likes of Legal & General, Sun Alliance and Norwich Union, although some were held by developers like Bell.

In contrast to the semi-rural, nostalgic imagery used to sell semi-detached suburbia at the time, modernity, convenience and sophistication were central to flat marketing campaigns. One of the largest developments, the 780-flat Du Cane Court in Balham, had a cavernous lobby, a social club, a bar and a restaurant, while the vast Latymer Court in Hammersmith claimed to be the largest block of flats in Europe at the time, with ‘the most modern style and amenities’. It was superseded by Dolphin Square in Pimlico, which featured over 1,200 apartments alongside its own upmarket restaurant, shopping arcade, tennis court and croquet lawn, all on the banks of the Thames, and later hosted Princess Anne, Harold Wilson, Christine Keeler, Rod Laver, and William Hague.

Perhaps the most luxurious, Eaton House on Grosvenor Street, Mayfair, boasted of being the first building in Europe with air conditioning. Others comprised small flats specifically targeted at single working people of more modest means, such as Russell Court in Bloomsbury and the White House on Albany Street in Fitzrovia (although the latter still managed to provide a swimming pool in the basement). These were rented at £60-£75 per year at a time when the average wage was around the £150 mark, making them relatively accessible.

Brighton & Hove was the one place outside Central London where Victorian mansion blocks had been developed, and unsurprisingly there are plenty of inter-war flats here too, with a notable cluster in the Victorian avenues west of Palmeira Square in Hove. Developments sprang up in other south coast resorts, such as Worthing, Bournemouth and St Leonard’s-on-Sea. The latter contains one of the most remarkable of these buildings, Marine Court, designed to look like an Ocean Liner; it still stands rather incongruously amid the regency buildings laid out by James and Decimus Burton, who incidentally also built much of Bloomsbury and Regent’s Park. (This area is one of the most fascinating places in Britain to visit at the moment, both architecturally and socially; it’s a case study in ongoing gentrification, as hipsters, artists and increasingly the more affluent colonise a once-genteel enclave that had fallen on much harder times. Marine Court itself is in the midst of refurbishment).

The boom also spread to some of the more distinguished suburbs in the big cities outside London, resulting in the 74-flat Queens Court in Clifton, Bristol and a collection in Jesmond and Gosforth in Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Osborne, Eskdale, Granville and Moor Courts. The single largest cluster, however, emerged in then-affluent Birmingham (which was also the most significant regional focus of the 1930s suburban housing boom). The earliest one, Calthorpe Mansions near Five Ways, was built earlier than most London blocks, in 1931; this was followed by the landscaped, multi-building Viceroy Court on the Bristol Road. Further west, on Hagley Road, Kenilworth Court, Norfolk Court, Moorland Court, Melville Hall and Westfield Hall are all in walking distance of each other, just outside the boundary of the Calthorpe Estate. There are a few others elsewhere in the city too, notably Pitmaston Court in Moseley, as well as lower-rise examples scattered around leafy outer suburbs such as Hall Green and Handsworth Wood. Bafflingly, despite their prominence, the Edgbaston set is not mentioned in any of the more prominent architectural guides, which prefer to focus on the stucco Regency and gothic Victoriana they are surrounded by.

The development of many of these blocks was led by local entrepreneurs Jack Cotton and Joe Cohen. The former would go on to be one of the world’s most successful developers, responsible for the Pan Am building and Grand Central Station in New York, while the latter became the founder of what would become the largest city centre cinema group in the country, Jacey (which was sold off and broken up in the 1980s). There does not appear to have been anything similar built in the other big Northern and Midland cities, except three small-scale examples: Appleby Lodge in Rusholme, Manchester (erstwhile home of Halle conductor John Barbirolli), a small block in Waterloo on the outskirts of Liverpool and one in Nottingham.

Everywhere, the designs tended towards understated Art Deco and modernism, but some were more avant-garde, notably around Hampstead Heath, with the famous Berthold Lubetkin-designed Highpoint in Highgate and Lawn Road flats in London’s Belsize Park. The latter block was built by Molly and Jack Pritchard, who owned the then-iconic Isokon furniture company, which made modernist plywood furniture in Estonia for export to the UK. The flats were supposed to provide an experiment in communal and minimalist urban living; they attracted a motley cast of residents, including the émigré Bauhaus architects Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer, an assortment of KGB spies and a couple listed as the Mallowans – Agatha Christie and her husband.

After the War

Construction ended abruptly with the outbreak of war. When peace returned, the establishment of the planning system, building licences, and a 100 percent tax on betterment – land value increases due to securing planning permission – meant there was almost no private construction until the 1950s. This situation was exacerbated by the return of tight wartime rent controls. The planning ethos of that decade, which emphasised reducing London’s density and ‘decanting’ to new towns, had little room for blocks of private apartments. Meanwhile, with parts of the city wrecked by aerial bombing and subject to intensive policies of slum clearance, urban living looked squalid and was a no-go area for private investors . The widespread construction of council-built flats in many areas – sometimes of poor quality – re-established and reinforced the negative connotations surrounding the form.

There was nevertheless a limited return to small-scale apartment building in the 1950s in certain more prestigious locations, but this time the units were for leasehold sale. As let properties were valued according to the rental yield – suppressed as it was by rent controls – while empty properties were assessed according to market value, boosted by the tax breaks given to owner-occupiers, operating a rental business made no sense and there were strong incentives to sell. As younger affluent people began moving back into parts of Inner London from the late (‘swinging’) 1960s onwards – especially during the subsequent ‘Barber Boom’ caused by cheap money policies during the Heath government – demand for owner-occupied inner city accommodation increased, further pushing up prices.

The post-war commercial property boom also saw the large insurance companies and pension funds sell out of their residential holdings and move wholesale into offices, which were being built at a tremendous rate in Central London in particular. Due to a loophole in the planning system most office construction did not need planning permission until 1963. Many of the 1930s private blocks of flats were broken up and sold leasehold; others were bought by local councils and used as social housing, while some were demolished and replaced with offices. (Incidentally, this means that the estimate of circa 56,000 flats in London, from a survey of those that were still privately held in the 1970s, is almost certainly a significant understatement of the original numbers).

While monumental flat development resumed in the 1990s, with schemes on previously derelict industrial land such as Montevetro in Battersea, the building of apartments to hold as investments has only become a feature again over the past decade or so. However, planning rules still mean that suburban intensification is impossible in most of our cities. Ironically, this means the trend has been most notable in the formerly industrial centre of Manchester, a city that was historically among the most resistant politically and culturally to flats.

Most of these blocks still stand today and some are quite distinctive features of the suburban London landscape, standing seven or eight storeys amid rather more low-rise environments; others are a more modest four or so storeys. Although they rarely exist in the same concentrations as the earlier mansion blocks, which can define whole areas of inner West London, there are actually somewhat more of them across the city as a whole. It is remarkable how little they have been commented on or discussed in books and academia – although to be fair they have been paid a little more attention than their completely ignored provincial counterparts. Indeed, it seems like the number of these flats outside London has never been counted at all. Perhaps they just did not fit in to the narratives authors and researchers had in their heads, providing neither the grand social housing projects or the privately built house-and-garden that appeal in different ways to specialists in this area.

This is all very unfortunate given the occasional argument that flats are only popular today because traditional suburban development is so squeezed. This history shows that even in the 1930s, when suburban houses were widely available, cheap and came with tax advantages for homeownership, many rejected his lifestyle and still wanted to live in flats in the city and the inner suburbs. And while families were not the typical tenants, the census data shows they were present, if not in large numbers. Indeed, the original blocks still have a lot of appeal. After broaching this topic on social media, I had quite a few messages from people of all ages who had lived in them and found them ideally suited to modern life, far more than anywhere else they had experienced.

Britain’s contemporary housing shortage is not just about the green belt and the lack of archetypal family housing. It is also about our long inability to provide sufficient and appropriate accommodation for the many people who clearly want to live and work in our cities – numerically far greater than in the 1930s, given demographic changes, the concentration of jobs in city centres and the greater appeal of an urban lifestyle (not least the fact that smog is no longer a problem). The comparative lack of inner-city density in British cities is also a major issue, constraining their commuter catchments and reducing both availaible public transport and their productivity. These flats seem like ideal historic examples of how to densify our cities while providing exactly the sort of accommodation that many smaller, busy households want and need: gentle, human-scale density with access to communal gardens and amenities.

This leads to the question of how this boom could be recreated. Without significant legislative and cultural change, it would be virtually impossible – at scale – to demolish old, overly large homes in affluent parts of London and replace them with flats of six to eight storeys; planning rules and local opposition would almost certainly prevent it. Attempts to allow moderate intensification in suburban Croydon have been scrapped after resident backlash. As a result politicians at all levels seem wary of supporting the new building of accommodation in the private rented sector too wholeheartedly, even though it has the potential to deliver a large number of additional homes. Leasehold purchases remain unattractive for many. However where development is politically possible, there is a strong demand for, and incentive to build, desirable mid-rise apartments.

In Salford, on the edge of Manchester city centre, a rare place where demand is high but development is generally supported, medium-rise apartments are being developed at scale. The puzzle is how these benign political conditions can be extended out into the relatively empty inner cities elsewhere outside London, as well as in those central and suburban areas of the capital which are incongruously sparse and low-rise, despite extremely high land values. Planning reform arguments tend to focus on the green belt and rural nimbyism, but the debate about how to recreate a very different type of 1930s boom should be just as important.

– Jon Neale is Head of Research and Insight at Montagu Evans.