Issue 21: The Great Downzoning

Plus: Why cities in poor countries need wider streets, how to measure competition, and the South Korean baby bust.

Works in Progress Issue 21 is out today.

Our lead piece is about the Great Downzoning: why, in the span of a few decades, nearly every city in the Western world banned densification, and what the Downzoning can teach us about reversing it.

This is our inaugural print magazine. Subscribers received the full magazine this week. Some articles have already been released online, and the rest of the issue will be published on the website throughout the next few weeks. We have already published pieces on:

What bacteria can teach us about evolution;

The return of inflatable space stations.

The rest of this issue will contain pieces on:

Why modern prose isn’t all about short sentences;

The origins of the South Korean baby bust;

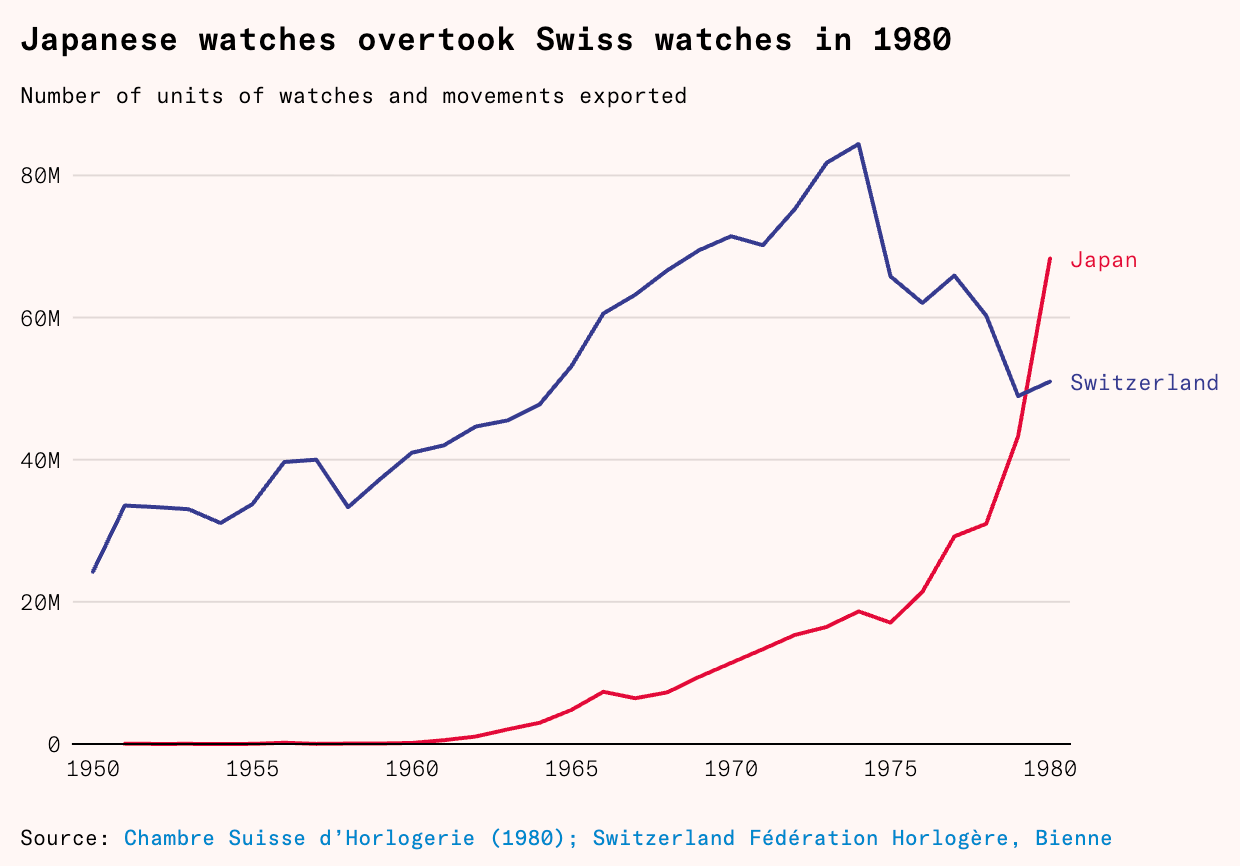

How quartz almost killed Swiss watches;

Whether classical statues were horribly painted;

How to measure competition; and

The use of genetics to develop drugs.

Subscribers also received features and columns exclusive to print, including Virginia Postrel’s inaugural column Nova Reperta. You can subscribe from the United States, United Kingdom, EU, Canada, and Australia. If you subscribe before December 18, you will receive Issue 21 and a new issue every two months after that. If you subscribe after that, you will receive Issue 22 as your first issue. If you live outside these countries and want to be notified as soon as subscriptions are live in your country, leave your details here.

The Great Downzoning is one of the most important events in economic history, writes Samuel Hughes. In a few decades, nearly every Western city went from a regime where it was legal to build almost anything, everywhere, to a regime where it is illegal to build most things in most places. Understanding why it happened is crucial to reversing it.

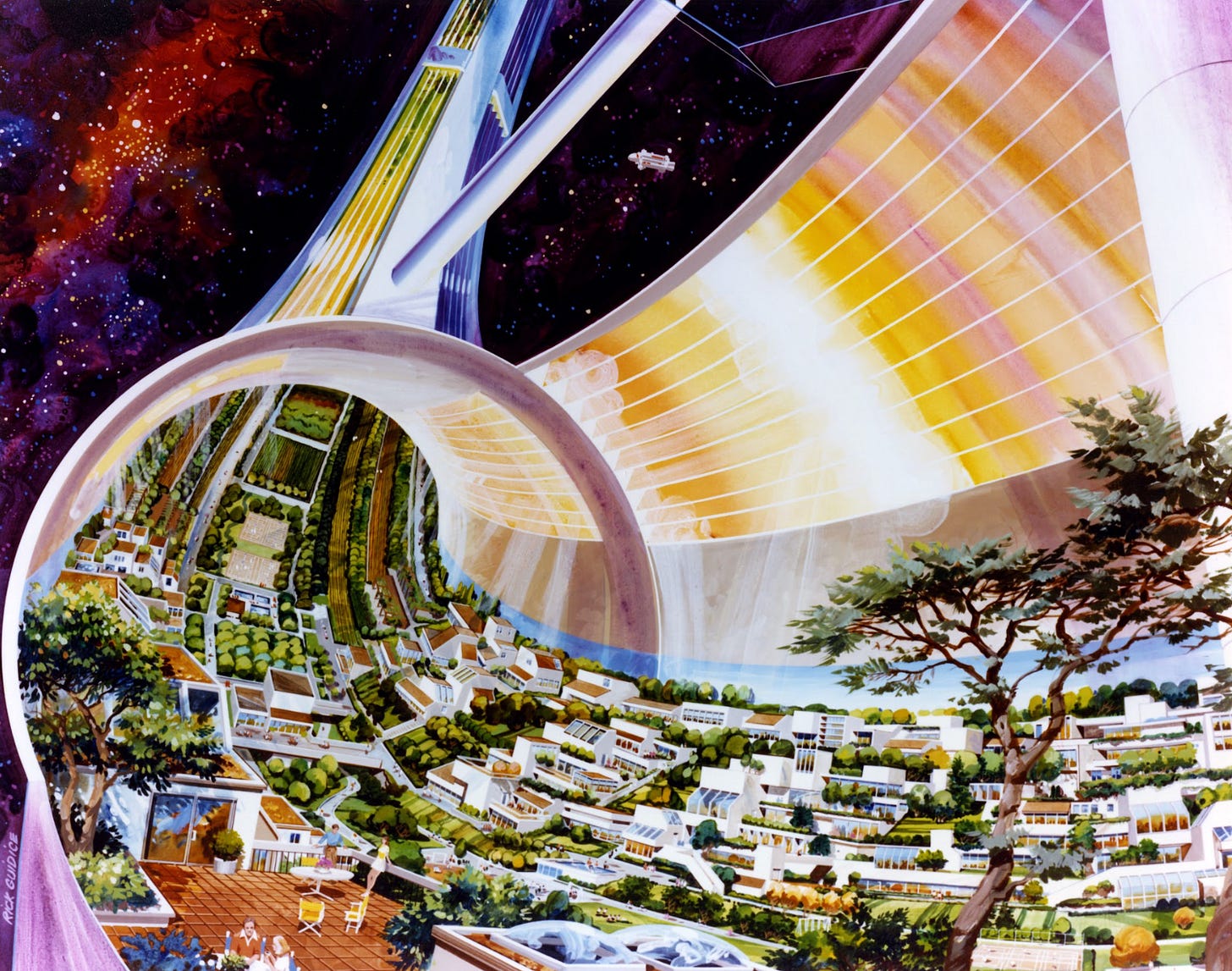

We need rotating space stations to create artificial gravity and live in space. Inflatable space stations are our best bet for creating something of that size, argues Angadh Nanjangud. We once abandoned them in our pursuit of the Moon, and eventually replaced them with rigid space Ikea programs like ISS. Now that Starship is available, it is possible to revive their promise – and make us a spacefaring civilization with technology and materials not far from what we have today.

If you want to see evolution happen within a human lifespan, you have to watch microbes, explains Kevin Blake. One long-running experiment has tracked 80,000 generations of bacteria, equivalent to two million years of human evolution. Another experiment led E. coli to develop antibiotic resistance in just ten days. Although Darwin was unaware of their existence, bacteria are the most visible proof of his theory.

Dishwashers took millennia to arrive, but when they did they freed women from hours of drudgery, writes Erin Braid. Ancient and premodern people, mostly women, scoured dishes with sand and ash. Although various earlier designs were tried, it was only in 1886, when Josephine Cochrane invented a dishwasher with pressurized water jets, that automatic washing actually took off.

A generous road endowment is the best thing a city’s leaders can leave their posterity, explains Saarthak Gupta, as the amount of agglomeration in a city is set by how many people you can actually reach, not the population living nearby. The Western world solved this in the nineteenth century by cutting boulevards through neighborhoods, enabling better transportation, including metros and trams and eventually cars and bike lanes; cities in poor countries today can give themselves these advantages for free by planning grids for new areas.

As well as these, which you can read now, we have six more pieces coming online from this issue over the next few weeks.

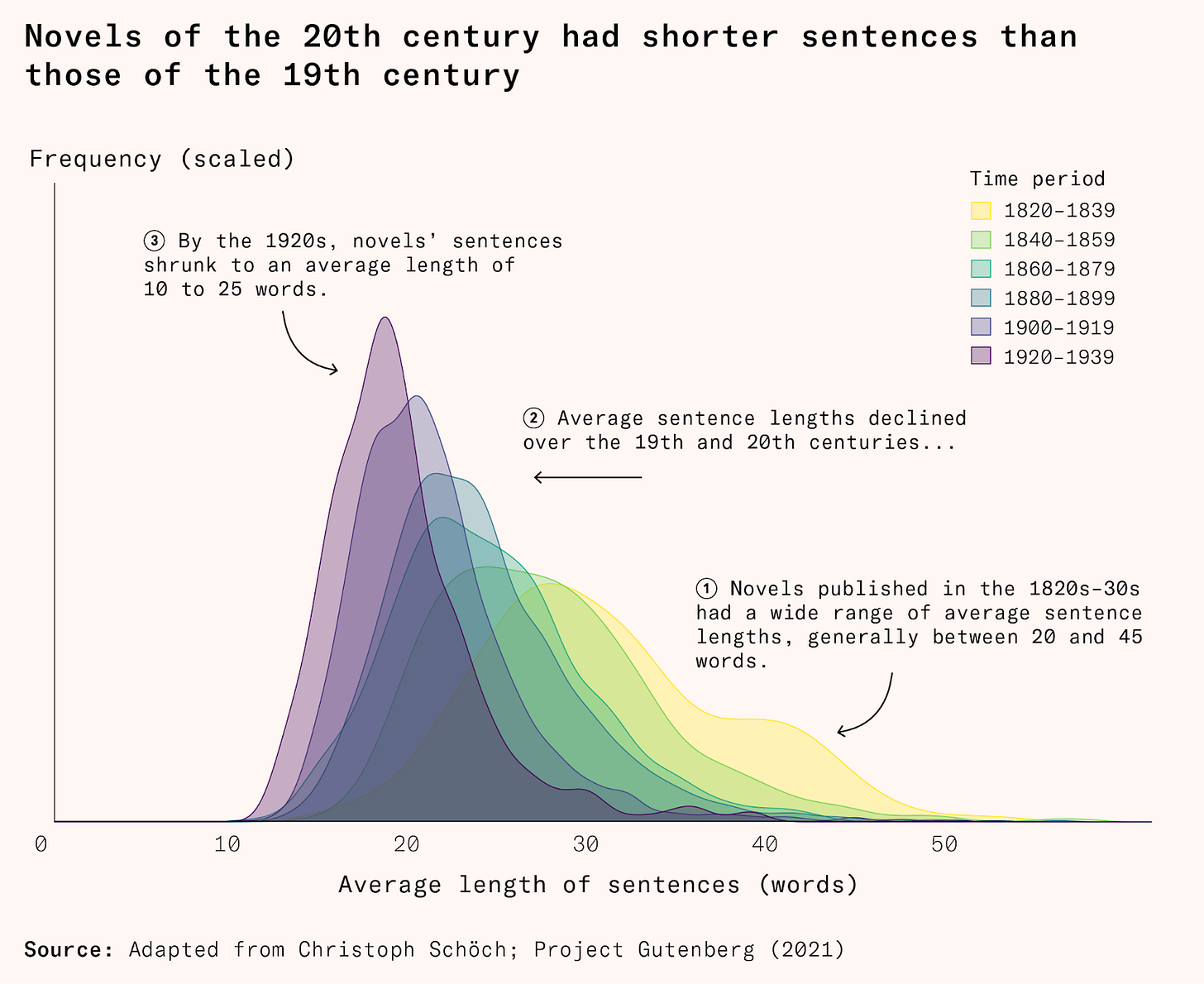

It is often thought that written English has become simpler and sentences have become shorter. But most contemporary prose is just as clear and logical as the English of a century ago once you account for differences in punctuation, explains Henry Oliver. The shift to plain, logical prose happened in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries when Tyndale, Cranmer, and others created sentences where meaning flows from word order, and pioneered the plain style of prose. The main difference today is that we write like we talk.

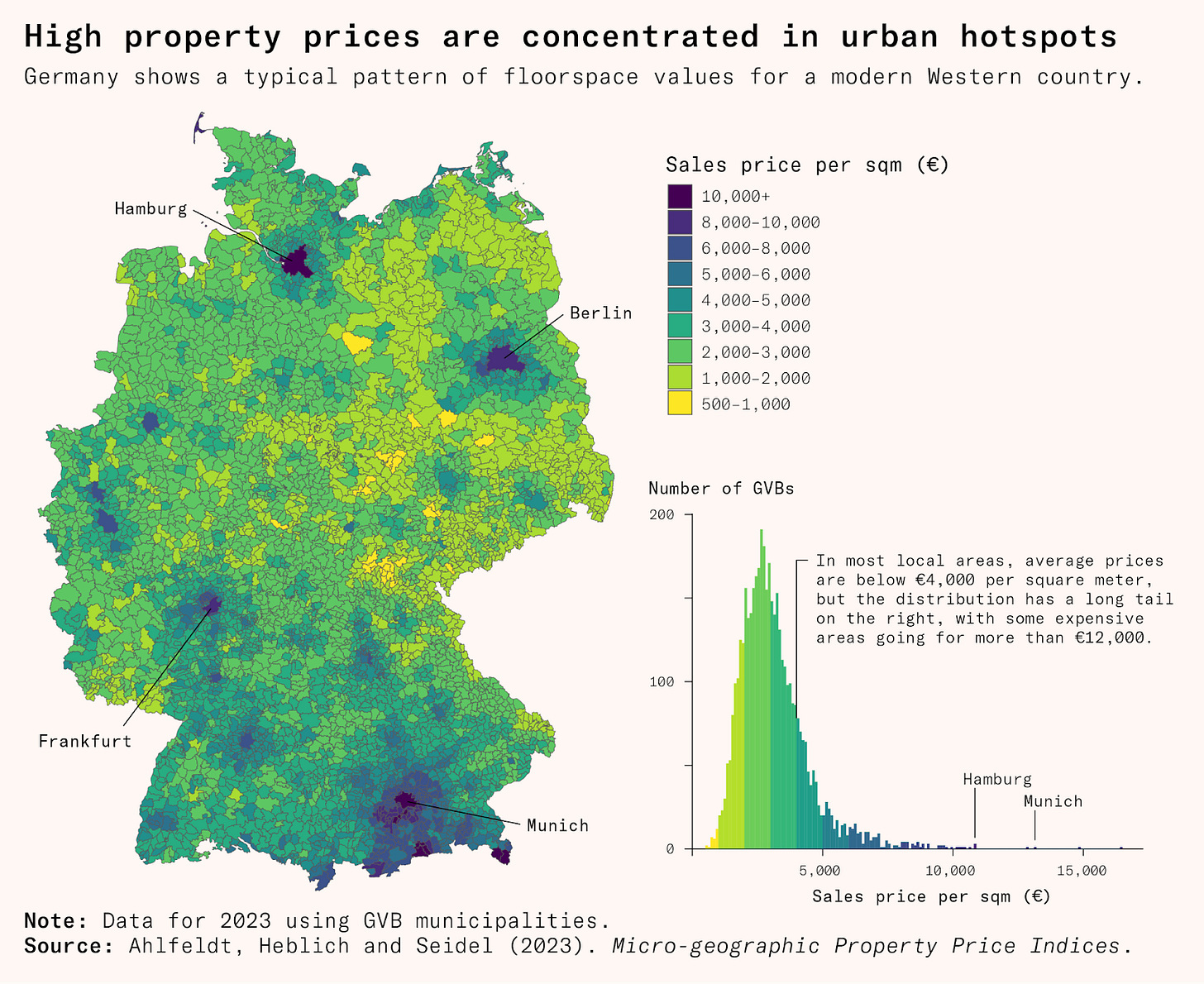

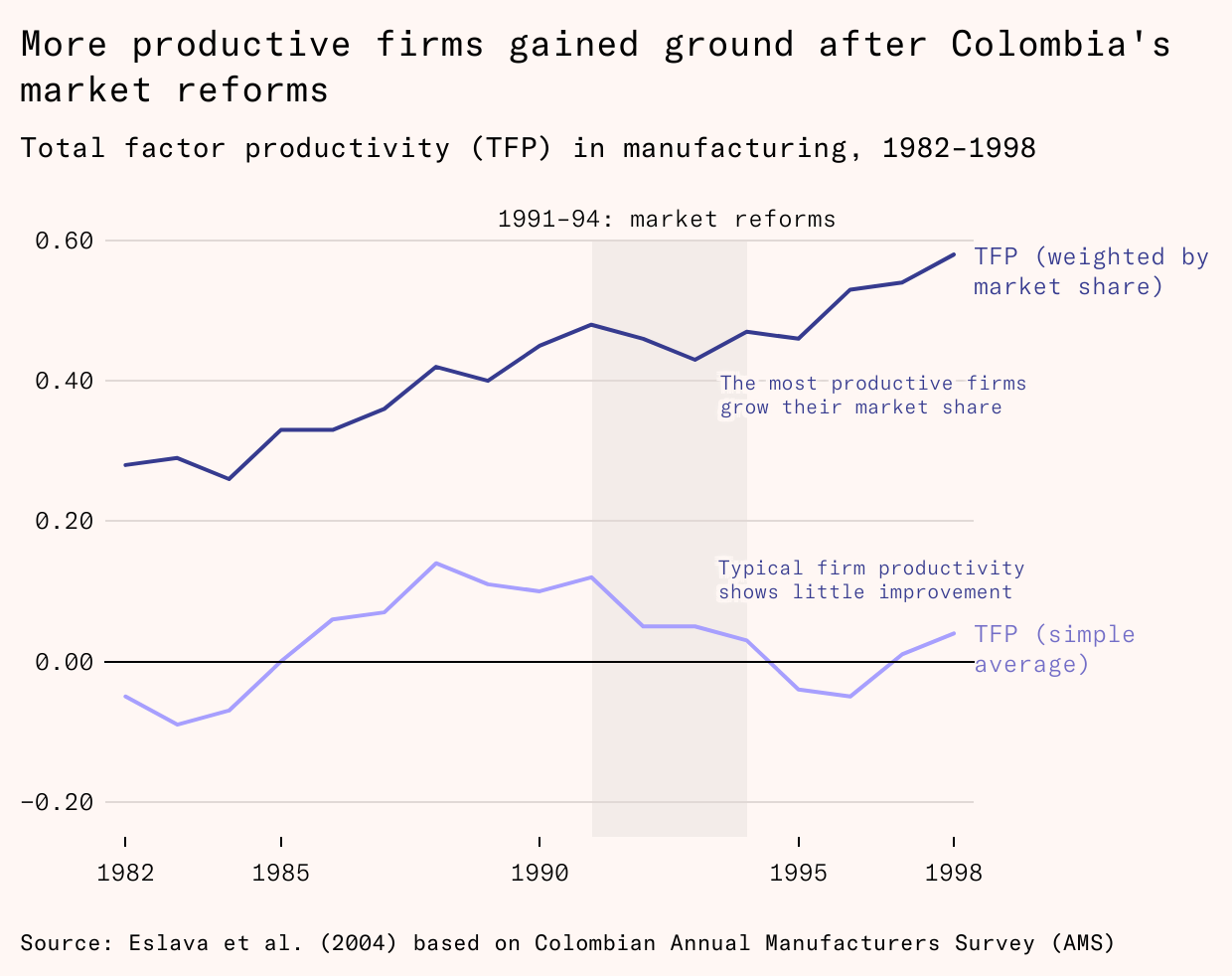

Almost everyone agrees that competition is vital to market economies; the problem is how to measure it. Market concentration and markups are misleading as they rise when markets are working well as well as badly. Instead, argues Brian Albrecht, regulators should use a measure which actually shows whether the most productive companies are gaining market share: the Olley-Pakes decomposition.

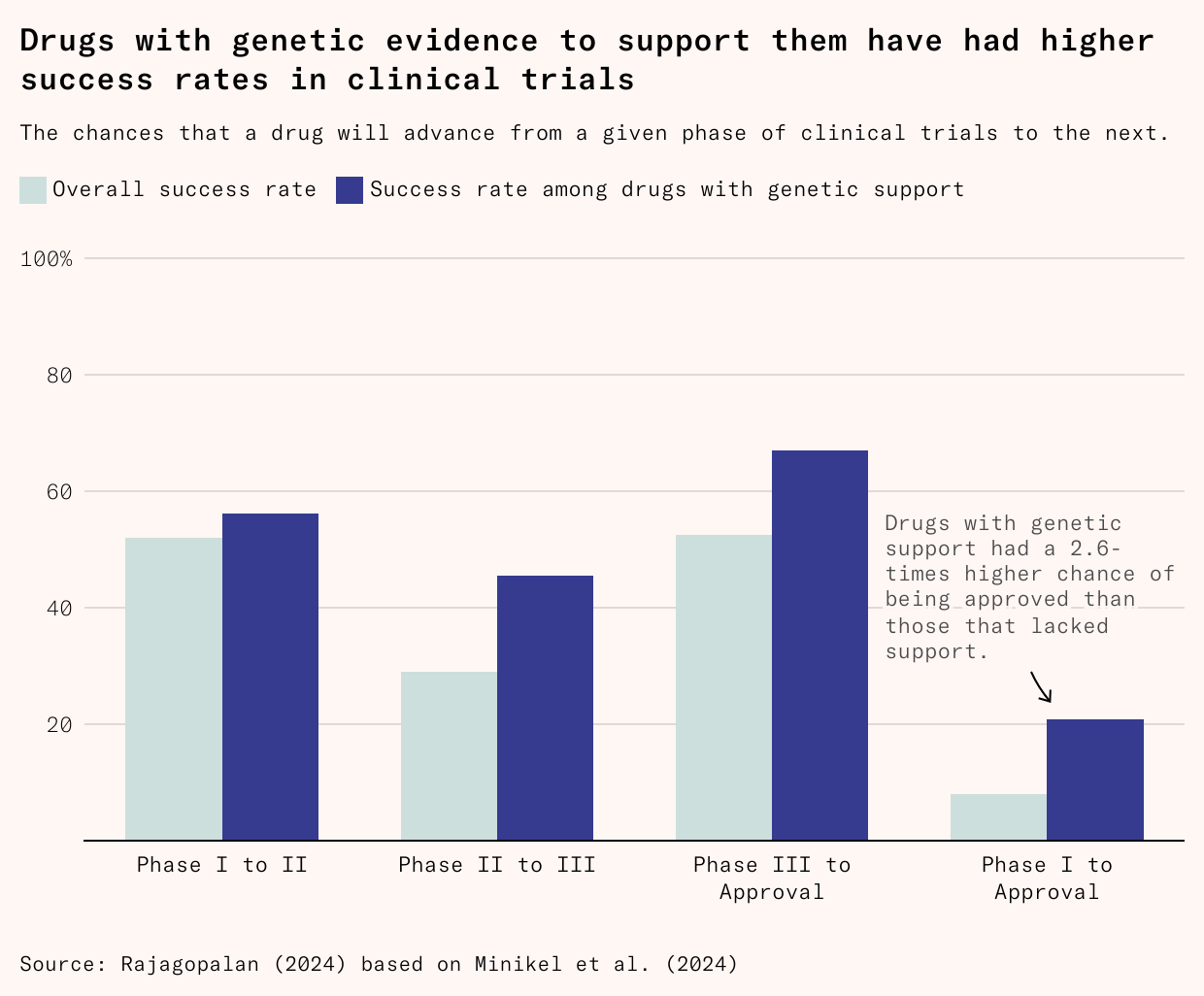

The biggest, longest, and most reliable drug trials have already been run, explains Veera Rajagopal: nature is constantly running millions of experiments through genetic mutations. These can reveal what outcome requires which protein, allowing researchers to find new drug candidates fast, and show what living with a protein is like, giving researchers safety data that spans human lives. By sequencing millions of genomes, pharmaceutical companies will soon be able to use nature’s laboratory.

South Korea is often thought to prove that pro-child subsidies don’t work. But, as Phoebe Arslanagić-Little tells us, South Korea’s subsidies do work; they are just insufficiently large to overcome world’s harshest career-motherhood tradeoff, most expensive child-rearing, and deepest gender divide, as well as decades of government antinatalism.

Swiss watchmaking should have died with quartz. That it didn’t, says Aled Maclean-Jones, was due to the foresight of a few men, including Jean-Claude Biver, who marketed Swiss watches as artistic objects, and Nicolas Hayek, who consolidated production and launched the twenty-dollar Swatch. Under them, Swiss watchmaking went from moribund to earning 45 percent of global watchmaking revenue.

Modern reconstructions of ancient statues look hideous not because ancient taste differed from ours, writes Ralph Stefan Weir, but because the reconstructions are badly done. Ancient depictions of statues show delicate coloring, and ancient frescoes and mosaics demonstrate a sophisticated naturalism we still find beautiful. The problem is with reconstructors, who based colors on surviving underlayers and failed to clarify this to the public. A cynic might suggest that they were deliberately trolling the public.

Hiring

Works in Progress is hiring a social media manager. Interested candidates should send resumes and fifteen draft tweets for the Works in Progress account to wip-hiring@stripe.com.

We would also like to make many more short-form videos for TikTok, YouTube Shorts, Instagram Reels, and Twitter. If you think you can do the job, email ababu-c@stripe.com.

Works in Progress is also interested in contracting for a podcast producer and editor. You need to be enthusiastic about what we do and ‘get it’, but also have some experience in the field, whether amateur or professional. Contact ababu-c@stripe.com.

Notes on Progress

Alex Kesin on the three-thousand year history of Colchicine.

Anton Howes on what makes Joel Mokyr great.

The Works in Progress podcast

The Works in Progress podcast put out episodes on building beautifully, with and without Nicholas Boys Smith. We also talked about politics with Congressman Jake Auchincloss and birth rates with economist Jesús Fernández-Villaverde.

Saloni and Jacob answered questions about AI and medicine. With two episodes on protein design and a four hour episode on whether AI will solve medicine.

What we’ve been up to

We hosted our inaugural event in Brussels. Ben spoke about the housing theory of everything; Samuel argued that the European housing debate should be more American; Fergus McCullouch of Progress Ireland explained how broken European habitats rules are, while Pieter explained how to fix them; Aria explained how cities drive innovation; and Robin Rivaton, CEO of Stonal, explained how recent reforms have ground the French growth machine to a juddering halt.

We put out a new list of pieces we would like to publish. If you know what we can learn from Japan’s 2004 pension reforms, whether we should give everyone antibiotics, or why Asia has higher density than Africa, please send us a pitch. As ever, remember that these are just guidelines, and we are always open to pitches on any topic you feel we might be interested in.

We hosted launch parties to celebrate Issue 21 with our subscribers in San Francisco, New York, and (tonight!) London.

Sam spoke about housing and growth in Vancouver, and appeared on the Existential Hope podcast.

Ben recorded a live podcast at LFG Make or Break with his Foundations coauthors. He wrote about the Nuclear Regulatory Taskforce’s secret weapon. He appeared on two Works in Progress podcasts, and he attended the Roots of Progress conference in Berkeley, CA.

Saloni has rebranded her newsletter Scientific Discovery under Works in Progress!

Rachel hosted pop-up bookshops with Stripe Press in London and Berkeley, visited one of England’s temperate rainforests, and threw a party to mark the anniversary of the Battle of Agincourt.

Pieter wrote about why Macron wasn’t a neoliberal and what a toad can tell us about Europe’s housing troubles, and interviewed Jesús Fernández-Villaverde on the economics of the baby bust.

Aria has been trying to find time to enjoy the new Taylor Swift album during an intense period of travel. In addition to the Progress conference she went on a long honeymoon across Europe for 15 days, 47 restaurants, 44 hours of driving and 45 hours on trains.

Alex has been touring the Middle East and telling every person he meets that the UK government should implement the recommendations of the Fingleton Review on nuclear power in full.

Samuel has been writing about how some nineteenth-century cities could double in population every five years. He has also been thinking about the invention of buses, how dense urbanism survived in Spain, contemporary Indian temple architecture, and how much it costs to build beautiful houses today.

Atalanta has been convinced by the Literature and History podcast that the tower of Babel was the Etemenanki ziggurat. She’s also been listening to the best podcast on sculpture in preparation for making her first bronze (start here if you like Michelangelo, and here if you like elaborate descriptions of siege machines).

Happy reading!

– The Works in Progress team

I wish I could keep up with all the great articles you and your team write!