Notes on Progress are irregular pieces that only appear on our Substack. In this piece, Samuel Watling explains why some New Towns succeed and others fail.

In the history of British planning the idea of a New Town is generally credited to the work of Ebenezer Howard. In his 1898 work To-morrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform he advocated for a new society of interlinked settlements, each composed of an urban core of gentle density surrounded by countryside.

With extensive government support, Howard and his successors attempted to put this vision into practice. The success of these schemes varied wildly depending on their location. Some became high quality places to live, while others dissolved into hideous settlements cut off from jobs and opportunities. The main factor that determined the New Towns’ success was not the design of the settlement itself, but the success of, and its proximity to, its parent city. New Towns near strong urban labor markets succeeded, but those further away or in economically depressed areas failed. Modern policy makers would be wise to heed this lesson.

The idea

The growing popularity of anti-urban ideas at the turn of the 20th century, coupled with improvements in transportation technology such as the electrification of railways, allowed city planners and dreamers to imagine more ambitious designs for settlements.

Ebenezer Howard was the leading figure in this movement, and aimed to create a system of what he called ‘town-country’. His planned ‘Garden City’ had a limit of 32,000 people, living on 1,000 acres of land (404 hectares, 4.04 square kilometers, or 1.5 square miles). The Garden City was then surrounded by 5,000 acres of countryside known as a green belt. His idea was to combine the opportunities and social life of a city with the amenities of a rural area.

Once the town had reached the maximum-allotted population size, another town would be founded and the process would repeat. These settlements would be linked by railways to create a network of hundreds of thousands, or even millions, of people.

The idea of setting up new settlements like these had strong historical foundations. Great cities such as Constantinople, Isfahan or Madrid had all grown rapidly by decree after demarcation by contemporary rulers as the main administrative capital.

Howard could point to recent examples of his vision of proactive planning, albeit on a smaller scale, by charitable industrialists in building housing in ‘model villages’ for their workers, the most famous examples being Saltaire, in Yorkshire, built by Titus Salt between 1851 and 1871, and Bourneville, in Birmingham, initially built by George Cadbury during the 1890s and 1900s.

The predecessors: The earlier New Towns

New Towns linked to older cores also had a history in the great 18th century building schemes of Edinburgh and Bath.

Both Edinburgh and Bath had developed New Towns in order to overcome specific constraints. In Edinburgh's case the constraint was geographic. The Old Town of historic Edinburgh was on a narrow ridge between the mountain of Arthur's seat to the castle. The 16th century Flodden walls, marshland to the south and a man made loch (lake) to the north made the city highly defensible.

But this also meant the city was unable to expand outwards as its population increased from 15,000 in the 16th century to 57,000 by 1750. All had to crowd into an area of little more than an 800 meter radius of the Leith Walk, leading to a population density of nearly 30,000 people per square kilometer, similar to modern Manhattan. The result of this land constraint was the building of tenements of up to twelve stories. As the contemporary English traveler Daniel Defoe remarked in 1724, ‘in no city in the world [do] so many people live in so little room as at Edinburgh.’

This high density created problems in a society without modern construction technologies. Sewage was dumped into the streets or the loch. Equally, without steel or glass frames, many buildings were structurally unsound. In 1751, a tenement building in one of Edinburgh's grandest streets partially collapsed, killing several members of a notable family. This forced the city to survey, and then demolish, much of its old housing stock.

In response to this crisis, the magistrates of the town council proposed an ambitious plan for ‘beautifying and improving the capital’ in a manifesto published in 1752. Its solution was to drain the loch and build a new town to its north.

In 1767, after draining part of the loch and starting to build a bridge from the Old Town to the site of the New Town, the Edinburgh council accepted architect James Craig’s plan for the New Town. The design envisioned a new settlement based around European architectural principles. At its center would be a nucleus of two squares, Charlotte and St. Andrews, joined by a straight half mile street christened George Street. The New Town would then extend outwards to the north, east and west in a grid pattern. Lacking funds to build the unified site itself, the council simply built sewage infrastructure and streets, and leased the rest of the land to private owners, subject to restrictions on street width, design and height. The result has become one of the world’s most loved and iconic cities.

By contrast to Edinburgh, where the issue with direct extension was topography, in Bath the constraint the New Town overcame was political. Bath had grown in popularity with tourists as a spa town throughout the 18th century. The architect John Wood wished to capitalize on this economic opportunity with an ambitious residential building project. Unfortunately neither Bath's landowners nor its council wished to sell him any land or facilitate any of his projects within the city walls. Luckily, in the 18th century Bath did not have a green belt, so Wood leased land on a local estate in 1728 and began building a New Town outside the walls instead.

Wood designed his first great residential square, Queen Square, and then sub-leased the land to local builders on the condition that they strictly followed his architectural designs for the exterior of the buildings. The project’s success after completion in 1734 gave Wood the money and reputation to continue building the New Town, completing the streets of North Parade and Duke Street during the 1740s. His greatest achievement, completed by his son 15 years after his death in 1753, was the design of the circus, a quarter of Bath centered on a 314-foot diameter circular square based upon the proportions of a Roman Amphitheatre.

This work continued by his son, John Wood (the younger), extended the streets west and east of the circus and linked it with his own masterpiece, the Royal Crescent, a continuous 500-foot-long crescent of 30 townhouses opening onto parkland. The circus and the crescent remain two of the finest examples of Georgian architecture in Britain.

In their urbanistic framework, Howard’s plans were similar in size and design to these 18th century predecessors. Howard’s proposed city planned for around 8,000 people per square kilometer, a density of around 40 dwellings per hectare at Edwardian household sizes, similar to the earlier New Town extensions of Edinburgh and Bath (and higher than the average density of most new greenfield developments in the UK today, which is 31 dwellings per hectare). Howard’s vision was of these slices of genteel urban life enveloped within a rural setting.

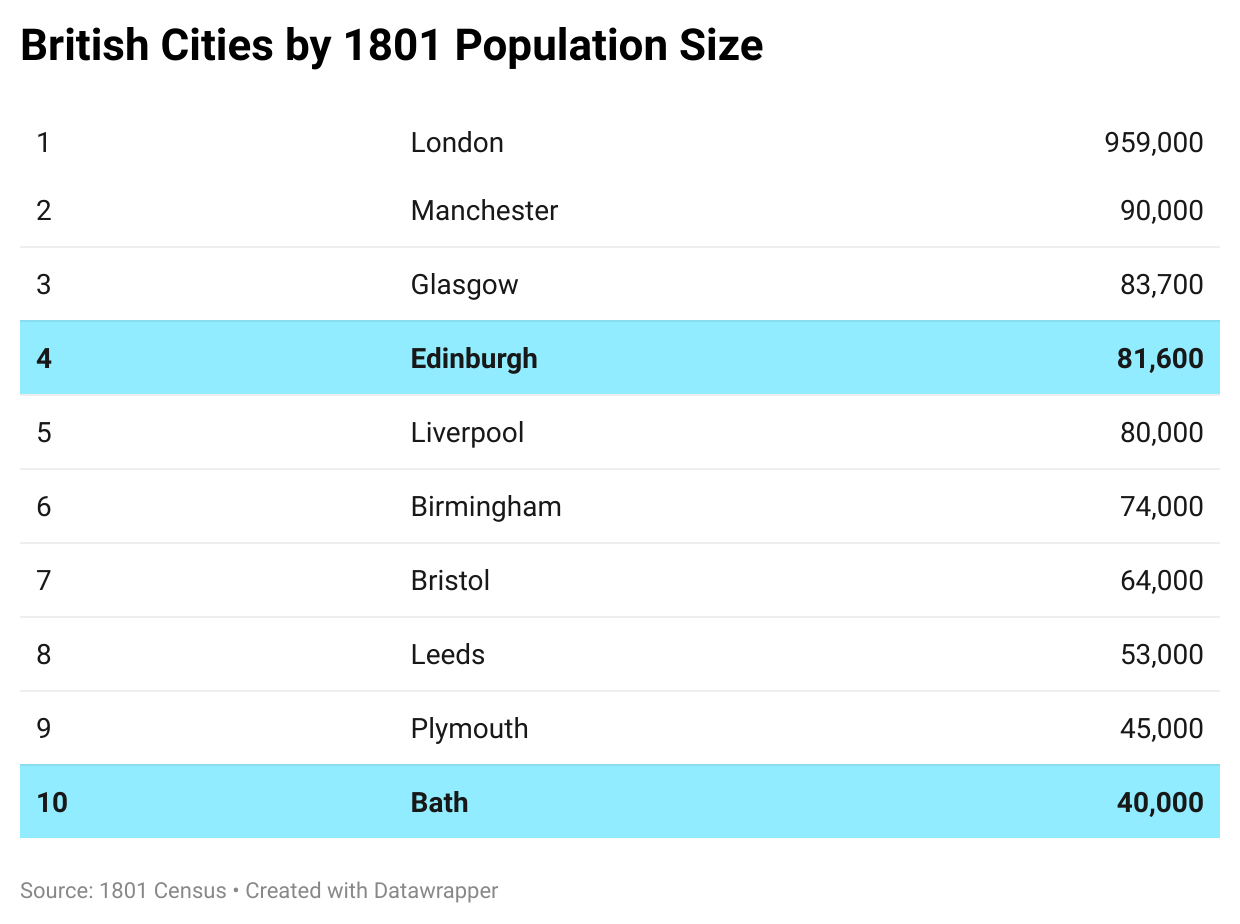

But Howard’s scheme diverged in economic rationale from those of his predecessors. Bath and Edinburgh New Towns were both interlinked with economically prosperous and growing parent settlements. By 1801, the total agglomerations of Edinburgh and Bath, including their New Towns, had populations which put them in the ten largest British cities.

What was different in Howard’s plan was its emphasis on a new self-contained social order. The Garden City Corporation’s plan was to buy land far away from existing population centers at cheap agricultural prices, develop it, and enjoy a rise in rent that Howard deemed inevitable. This rent would flow back to the municipality instead of private landlords (similar to the experimental Georgist cities in the USA). Once it had adequately reimbursed investors, any further increments could fund social programs.

Howard’s model worked under the implicit assumption that location was essentially arbitrary: it didn’t matter where the New Towns were. Their land value came from public investments and economic activity, not any inherent value from people living near one another. This was an idea that brought his project to the brink of failure.

1898–1945: From Garden City to Garden Suburb and back again

In 1898 Howard founded the Garden Cities Association to put his ideals in practice and found a New Town. Within two years, 1300 people, including the economist Alfred Marshall, had joined him.

Ironically, the association implicitly admitted location mattered when they chose Letchworth (34 miles from London) over a site near Stafford (35 miles from Birmingham) because the former had better transport links to London. The Association bought a 3,818 acre (1,500 hectare) site for £155,587 and founded the first Garden City Company on September 1st 1903. The architects and planners Richard Unwin and Barry Parker made a master plan for the city.

Building this utopia was more difficult in practice. In practice, and against Howard’s theory, land values reflected the desirability of a location. Low land values reflected the fact that neither industrialists nor workers wished to flock to a new settlement with relatively poor transport links to existing agglomeration networks. Private investors were not keen to invest in isolated communes. As a result, the Garden City Corporation could only raise £40,000 out of the £300,000 it needed to build the town, all from its directors, meaning no money for public buildings.

In the first two years of the city only one thousand new residents, less than one-thirtieth of the target population, arrived. Even the high architectural standards (and thus costs) of the master plan proved a hindrance to the town's growth: most workers could only afford to rent lower-quality properties outside the city.

Hurtling towards failure, the enterprise was saved by jettisoning Howard and many of his ideas. Ebenezer Howard was cut out of decision making and the land was leased privately to businesses and builders. The gentle density and ideals of collective ownership dissolved into an ordinary, privately owned suburbia. Some industry, most famously the Spirella factory (which produced made-to-measure corsets), eventually moved in, and the town grew into a conventional working-class satellite town of London, albeit far slower than intended, with only 18,000 people by 1938.

The Garden Cities Association and its leading members learnt from this bitter experience and compromised. Unwin went on to design Hampstead Garden Suburb, a small planned settlement then on the outskirts of London, which began construction in 1907. The Association founded Welwyn Garden City, 20 miles from London, in 1919. The residential areas of these settlements were still planned on similar architectural and urbanist principles to those of Letchworth. However they made no pretense to be economically independent, instead explicitly relying upon London, their parent city, for employment. The Metropolitan Railway Company followed this example, using the land it owned near rural stations to expand nearby market towns such as Chorleywood and Amersham into the commuter settlements of Metroland.

These new settlements were quickly occupied and economically successful. Raymond Unwin made sure their success influenced official policy. He advocated the building of New Towns in satellite commuter locations as the primary method of the 1920s and 1930s government public housing programmes. In this he was largely successful. Urban councils funded major works of suburban building in master plans, which produced one million public houses (i.e. council houses) in the inter-war period. In London, this included the large Beacontree estate in Dagenham, where 24,000 new homes were built on 3,000 acres of market gardens in Essex. Likewise, Manchester built over 8,000 houses on over 2,500 acres of farmland in the Wythenshawe estate to its south.

The Post-War New Towns

Yet despite the success of satellite New Towns the idea of self-sufficient New Towns once again became dominant in the 1930s and 1940s, due to a political backlash against suburban development and urban expansion during the 1930s.

The government accepted the recommendation of the Barlow commission to increase government planning powers to halt urban expansion and disperse the urban population. New Town advocate and planner Patrick Abercrombie was on this commission and helped infuse its eventual report with strong preference for New Towns as the primary method of dispersal.

However, the government needed to decide how to finance the New Towns and who would be in control. Major private builders such as Taylor Woodrow, John Laing, and Wates offered to take contracts for New Towns. However, the Garden Cities Association, now renamed the Town and Country Planning Association, or TCPA for short, wanted the state to build them itself.

In 1945, the new Labour government’s planning and housing minister Lewis Silkin appointed Lord Reith to head a commission to decide. Silkin stacked the committee with members of the TCPA, who outnumbered the private sector representatives. In the end, the government passed the New Towns Act on 1st August 1946, before Reith’s commission even formally published its report. This enacted the TCPA’s wishes and the government set up state-led development corporations with the aim of constructing several New Towns with populations in the range of 20,000 to 60,000.

Success

The logic of the post-war New Town projects was that the use of state power would make them succeed where the voluntary efforts of Ebenezer Howard had failed. They would forcibly channel development from the cities of the South East and Midlands to these self-contained new settlements. The post-war planning framework gave the planners extensive powers to make these dreams a reality.

The first wave of New Towns primarily involved the expansion of small market towns between twenty one and thirty two miles from London such as Harlow, Stevenage and Basildon. Each town’s development corporation took on planning powers from the local council and exercised complete control over the town's master plan. They had the right to buy all land in this original master plan at pre-existing (agricultural) values. They would then commission and build all the housing in the plan. Yet the development corporations’ powers did not just stop there. To enable self-containment – that is, to stop the towns being dormitory towns for London commuters – they could choose who they offered their houses to and which industries were located in them.

As part of the attempts to decentralize the economy from 1945 to 1981, the British government required that all industrial buildings above a certain size had to obtain an industrial development certificate (IDC) from the central government before applying for planning permission from a local authority. Throughout the period the government was reluctant to permit applications in the South East and Midlands, forcing much new industry in these regions to take place in formerly abandoned aircraft hangars and warehouses.

However, there was an exception to this policy for New Towns in the South East, which the government believed would help to ‘counterbalance’ London. This meant that businesses that wished to expand around London would accept strict conditions to be allowed to establish themselves in a New Town as well. New Town development corporations only gave the right to build factories to companies that accepted that their workers would live in the New Town, and the corporations only offered houses to people who had a job offer with a local company.

Yet despite the emphasis on self-containment, Silkin understood that companies could not move more than 30 to 40 miles from London as London provided the necessary transport and markets for the displaced industry. These New Towns, despite being physically separate from London, also required good rail connections to the city to avoid the problems Letchworth had faced. It was this proximity to London that saved these ‘Mark I’ New Towns in the long run. As British industry entered terminal decline from the 1960s and the economy shifted towards urban-based services, the residents of these New Towns could eventually commute to London for work. By 2011, over half the workforce of Stevenage commuted to London. Like their predecessors of Hampstead and Welwyn, the Mark I New Towns ended up as satellite towns.

They were not without problems. The creation of major settlements from scratch had high upfront infrastructure costs. Entirely new systems of transport, electricity and sewage had to be created from scratch. Meanwhile, the New Towns were initially subject to strict controls. The government forbade them from selling the houses they built. They instead had let them out at the artificially low terms allowed under post-war rent control legislation. High costs and restricted revenues led to designs that were austere and underwhelming, a fact exacerbated by planners’ preference for modernist designs.

Unsurprisingly, local residents of the locations designated to be New Towns opposed them and put up fierce resistance, though these could be overcome by determined ministers. Silkin overrode residents’ associations, planning inspectors and even court injunctions to designate the New Towns around London. His Conservative successor Harold Macmillan, who was intent on building out Silken’s towns, rebuffed Treasury demands for funding cuts by commissioning endless departmental reviews that were little more than delaying tactics.

Yet the opposition from residents and the Treasury eventually triumphed. After 1950 the government did not create a new New Town for eleven years. In 1955, the government allowed the expansion of greenbelts around London and promised not to use the New Towns powers to overrule these designations.

Failure

With development in the vicinity of London ruled out, the planners had two choices left. Either to build new settlements close to other cities, or build them further out from London. They tried both. From an economic perspective the Mark I towns near London had been a qualified success, providing their residents with jobs and housing. However, according to planning doctrine, despite the stringent controls over their residents' employment they were still too dependent on their parent cities.

To avoid this in future, planners resolved to set up larger and more remote New Towns. The 1964 South East study changed planning guidelines to suggest that further New Towns should be built at considerably greater distances, 50 to 80 miles, to maintain ‘functional separation’ from the capital. Only two of the proposed settlements in the South East materialized. One of these, Milton Keynes, was fortunate enough to be on a railway line between London and Birmingham, and still within a reasonable commuting distance of robust urban labor markets. The other, Peterborough, was 90 minutes away from London by train, and as a result far less successful than its predecessors, with a median wage 20 percent less than in Stevenage in 2022.

However, most of the second wave of New Towns provided space for the overspill population displaced by slum clearance in northern cities. Their parent cities could not accommodate the people there within the city due to greenbelt restrictions.

These New Towns that were outside the relatively prosperous South East fared even worse than Peterborough. Some towns such as Runcorn and Telford were theoretically viable as satellite settlements, both being within 20 minutes commute of their parent cities, Liverpool and Wolverhampton respectively, However they suffered when the economies of their parent cities nosedived in the economic crisis that followed the 1973 oil shock. Unemployment reached up to one fifth of the labor force in these areas by the 1980s, like much of the rest of that part of the country.

Some settlements faced the worst of both worlds, being both isolated and in economically deprived areas. The most notorious of these was Skelmersdale. The government founded Skelmersdale in 1961. Situated between Liverpool and Manchester, it took the overspill from the slum clearance of Liverpool. By the early 1960s the Liverpool county council predicted that it would have to clear an estimated 84,000 dwellings deemed unfit for human habitation. But there weren't enough places in the metropolitan area where either planners or the local councils could put those they had displaced.

The scale of initial overcrowding was so great that once these 84,000 homes had been replaced and people rehoused in new flats, getting back to reasonable levels of crowding involved rehousing a further 80,000 people elsewhere. Accommodating these people by building on the urban fringe or by extending the local towns of Ellesmere Port or Runcorn was unpopular with the planning establishment. Expanding the city would lead to ‘urban coalescence’ (aka urban sprawl), and building on the Merseyside greenbelt would affect ‘valuable farmland’.

The only other appropriate site for a new settlement of 80,000 people was that of Skelmersdale, a site further out, around 15 miles from Liverpool. This distance in itself was not too high, similar to that of the Mark I Town Crawley, south of London. The problem was that British Rail had shut Skelmersdale’s railway station in 1956. The only public transport to the nearest cities of Liverpool or Manchester was a bus which took about 90 minutes.

Without links to nearby urban labor markets, Skelmersdale would need to develop a local industrial base, but its location also made this difficult. Post-war Liverpool was an area of historically high unemployment, and central government policy between the Second World War and 1979 used planning controls and subsidies to try to direct industry to it and other deprived regions. Creating employment through these means was difficult enough for a core city like Liverpool, but even worse for Skelmersdale, whose location put it outside the area targeted for development. This meant that industry in nearby areas received a subsidy but industry in Skelmersdale did not.

Things got worse. During the construction of Skelmersdale in the 1960s and 1970s, the industrial economy of the Merseyside region went into severe decline. By the time of the 1982 recession, unemployment in the Skelmersdale New Town hit 34.3 percent, the highest in the country (outside of politically unstable Northern Ireland). In 1985, the government scrapped plans to complete Skelmersdale, leaving it with a population of less than half of what planners intended. The town still suffers from endemic poverty today. Fourteen out of 23 districts in the town are in the poorest 20 percent of districts in England.

Conclusion

The idea of master-planned New Towns is older than formal urban planning itself. It is easy to see the appeal of starting fresh with a new urban form, leaving aside the problems of the old city while keeping its benefits.

Yet, as we have seen, the value of all New Towns is not equal. The aim of the New Town pioneers of the early 20th century was to recreate a good urban environment from scratch and in doing so obtain the benefits of large cities without their negative externalities. Yet this ignored the central fact that location matters. It is only possible to construct successful new settlements when they are near economically robust cities.

Ebenenzer Howard made a radical attempt to escape from the city and create a new Utopia. In the end he built some respectable suburbs, but not a new society. Yet having failed to create his dream voluntarily, planners attempted to do so by the coercive measures of state planning. Despite the vast power over both the planning system and market that the New Town corporations had, the first, relatively successful, generation of New Towns remained economically integrated to their parent cities.

Planners then decided to push the concept of self-containment to its limits and in the 1960s founded New Towns beyond the reach of any successful agglomeration. These attempts were mostly failures that condemned their residents to poverty.

Modern experience suggests that British planners have not learnt the mistakes of the past. The most recent attempt at New Town development in Britain, Northstowe, eight kilometers outside Cambridge, has 10,000 homes planned for with government support. Yet its isolated location means that it has no railway stations, shops or GP surgery, so its inhabitants have to drive everywhere.

Yet we know that these failures are optional. The success of the original New Towns of Edinburgh and Bath were not just due to good architectural decisions on the part of the designers, although these certainly helped. They worked because they were in places where people actually wanted to live.

The British government appears to be beginning to accept this fact. It has announced the building of a Cambridge New Town of up to 150,000 new homes directly adjacent to Cambridge’s existing built-up area. The new plans for New Towns specify that most will be urban extensions instead of standalone settlements. And there are places where new settlements could work. Samuel Hughes and Kane Emerson have suggested founding a New Town at Tempsford, where the East Coast Main Line and the new East West Rail line intersect. In their proposal, the development of the New Town would provide money to upgrade the Main Line, allowing the New Town to be a 20 and 40 minute train journey from Cambridge and London respectively. The promise of New Towns can still be realized – if they work with, rather than against, the facts of economic geography.