Notes on Progress is a diary-style format from Works in Progress. If you only want to hear when we have a new issue of the magazine, you can opt out of Notes in Progress here.

In this issue, Ben Reinhardt announces his new ARPA-style lab, Speculative Technologies, and tells the story of his career that brought him to founding it. If you enjoy it, please share it on social media or by forwarding it to anyone you think might find it interesting

I have a deeply etched memory of a sign on a building with a quote from Theodore von Karman:

Scientists study the world that is. Engineers create the world that has never been.

My career so far has been a wandering journey from one institution that I thought was responsible for building the future to another: from academia, to NASA labs, to high-growth startups and venture capital. In a nutshell, I’ve been on a quest to find the right institutional home for the work to create the world that has never been.

When I graduated from college as a fresh-eyed mechanical engineer, I was under the impression that incredible new technologies—from morphing aerial vehicles to self-driving cars—came out of academic labs. So many press releases are of the form: ‘Researchers at XYZ university announce that they have built the first <cool thing>’. I didn’t even consider startups as, in 2010, tech was almost synonymous with software. (Check out the list of YC companies from before 2011 filtered by non-software things - it’s brief.) To some extent I was also avoiding what I didn’t want to do: all the work in ‘industry’ seemed to be approximately ‘make a box to these specifications’. So, wanting to do a bit more than build better boxes, I applied to grad school.

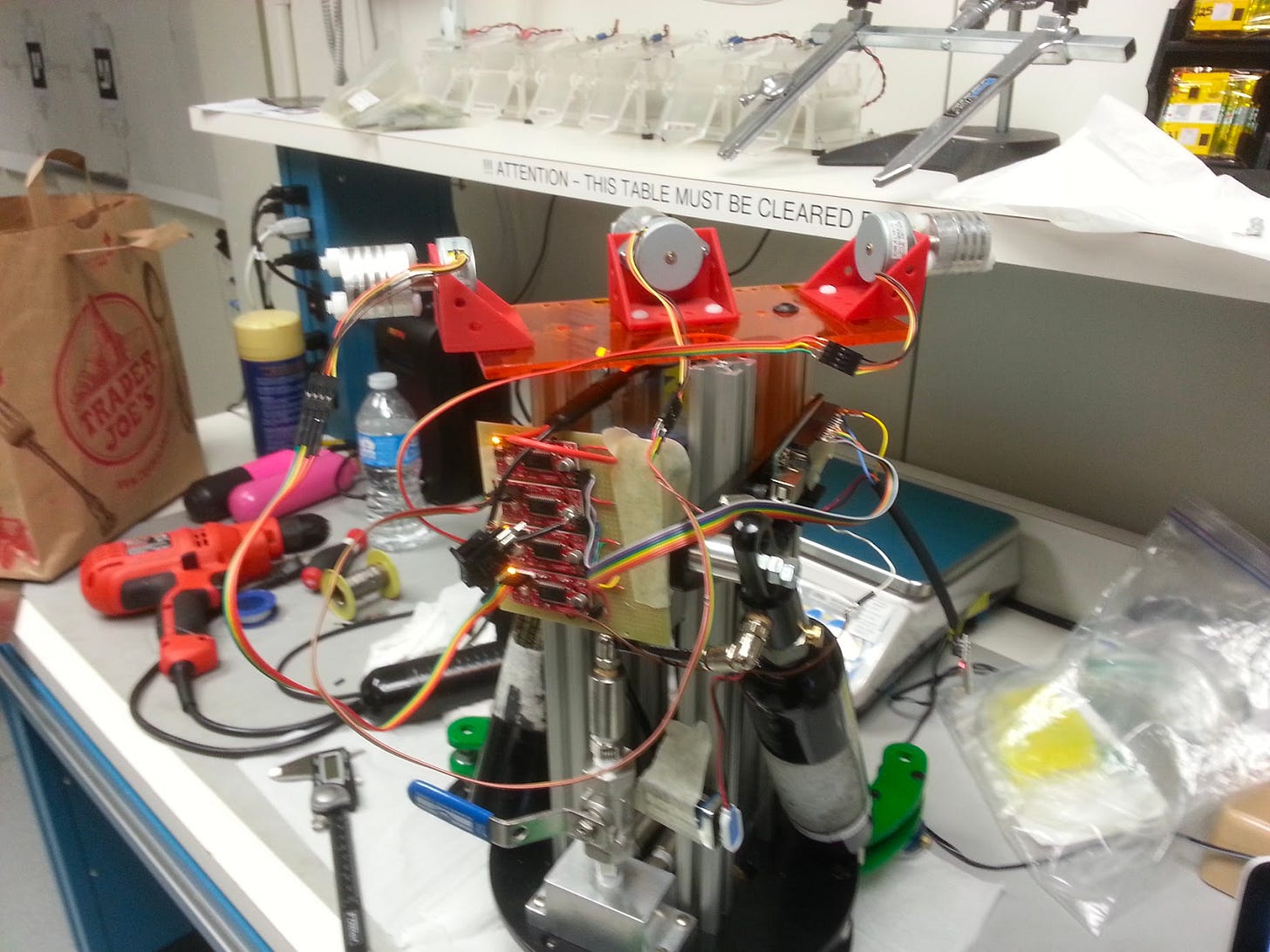

My PhD work focused on building an electromagnetic ‘tractor beam’ that would enable a robot to crawl around the outside of a space station or satellite.1 Cool, right? Academia is absolutely the place to suggest new technologies. In fact, if something is too similar to something that someone else has already done (i.e. insufficiently novel) people will look at it askance. On top of the demands for novelty, many academics feel intense pressure to publish as frequently as they can, especially in top journals. I managed to avoid that particular trap because I quickly realized that I had no desire to stay in academia.

Academia taught me that interesting new ideas alone don’t create the world that has never been. There are thousands of technologies that obey the laws of physics and seem like they should upend how we do things, but are just ‘sitting on the shelf’. (Just browse through the NAIC (NASA Advanced Innovative Concept2) studies and you’ll see everything from telescopes on the far side of the moon that would blow the James Webb out of the water to power beaming to a low-boom supersonic flying wing.)

Creating the world that has never been needed more than just a search for novelty. It needs functional systems to get built and used. So if academia wasn’t the right place, where was?

As part of the fellowship that funded my PhD, I worked at NASA during the summers. I sat in a garage next to a tank-sized, hexapodal moon rover and worked on building a rig to physically simulate microgravity in three dimensions, among other things. Unlike academia, NASA (and the US government more generally) does have a mechanism for enabling new technologies to see real action.

However, everything NASA (and the government more broadly) does needs to be justifiable to Congress and the American taxpayers. But the history of impactful technology is littered with examples of work that was hard to justify in advance—‘If I had asked what people want, they would have said “a faster horse”’ is a trope because it’s true.

On top of justifiability, government work is subject to political currents, resulting in technology like the Space Launch System, which costs $1.2 billion per launch (in part because legislation mandates which components must be made in which constituency and in part because, for some reason, NASA gets a new 10-year-plan every eight years). As a result, the majority of government technology is one-off, outside of the military. Sometimes that’s fine: you don’t really need more than one James Webb Space Telescope. But often the key to technology is achieving scale: We would live in a very different world if airplanes, cars, or electric lights existed as rare curiosities.

Creating the world that has never been requires speculation and scaling general purpose technologies, not exquisite one-offs. What institutions alway talks about impact, scale, and building the future? Startups and tech, of course!

The startup bug bit me hard. By that time—2015—what we now call 'deep tech' was starting to become a thing. Startups were tackling problems beyond software in the World of Atoms. When I finished my PhD, I managed to get a job at a Magic Leap building augmented reality headsets. At the time, AR seemed poised to completely change how we interact with the world.3 It was on the quintessential startup trajectory—valued at over a billion dollars, top tier investors, breathless press pieces. But the technology needed more research, not just product development, to achieve its full potential.

Unfortunately, with great funding comes great expectations: to justify a massive valuation, startups need to show constant results along a trajectory towards massive scale. Like so many other weird new technologies, that pressure forced a number of short-term design decisions that made the headset no different than anything else on the market and arguably killed the technology’s possibility of having a massive impact.

Disillusioned, I thought ‘surely if I started my own startup, I wouldn’t fall into that same trap! I could build out a new technology slowly, setting expectations with investors along the way.’

So I tried it.

Impelled by some horrific family experiences with elder care, I started a company to deploy remotely operated robots that we hoped would enable older adults to get affordable care in their homes while maintaining independence. The idea was to enable one person to operate multiple modified telepresence robots to check in on people with dementia who didn’t need physical help, and then incrementally build on physical capabilities. It seemed like the perfect way to leverage robotics skills from my PhD program in a way that was at once technically ambitious but also close enough to the market to be a startup.

However, I couldn’t figure out a way to do it without falling into the same cycle: a large round of investment led to high investor expectations, high investor expectations led to compressed timescales, compressed timescales led to worse technology or failing to meet expectations. I maintain the belief that creating those remotely operated household robots would still be incredibly valuable to humanity but the structure of the eldercare industry meant that it would be hard to capture much of that value—that is, until the robotics was much more mature, what I was proposing would be a bad business. (It didn’t help that I am terrible at sales.)

But what if I were the investor? Could I fund deep tech companies with pre-tempered expectations and allow them to develop groundbreaking technologies at their own pace? So, like many failed entrepreneurs, I did a stint in venture capital.

I quickly realized that all the incentives I sought to escape followed me: professional VCs have their own investors who expect a sizeable return. After all, venture investments are less liquid and higher risk than the stock market, so VCs need to outperform it. Achieving large returns with a portfolio of high-risk companies means that any particular company needs to imaginably become incredibly valuable on a fairly compressed timescale: investments are judged not just on the amount you can increase invested capital, but the timescale over which that increase happens. That denominator is the reaper that comes for research-heavy startups. There are notable exceptions, but outside of healthcare and software, research-heavy startups are vanishingly rare.4

It started to dawn on me that maybe my quest was ill-posed. Maybe there wasn’t an institutional structure that supported work that still required research, wouldn’t necessarily create capturable value, but did aim for impact and scale, yet wasn’t bureaucratically legible.

If there is something that academia, NASA, and the tech industry agree on, it’s that if you need something that doesn’t exist, sometimes you just need to build it yourself. So, putting my academic hat back on, I started digging first into the institutions that did seem responsible for creating new worlds—their histories, mechanisms, and flaws. Venture capital as an industry was incredibly path-dependent—arguably it wouldn’t exist without the combination of early lucky wins for the model, a few bull-headed individuals, the emergence of industries with low marginal costs, and timely regulatory changes.5

The great industrial research labs, PARC and Bell Labs, were immediately salient as the birthplaces of modern computing, but depended on the support of parent companies with monopoly-driven profits. The companies that currently fit that bill care mostly about software and I didn’t think I could pull off a plan that started with ‘Step 1: create the next AT&T.’

While the American government research system is surprisingly new, largely invented in the wake of WWII, it is so entrenched that I couldn’t see a way to reinvent it: it will take someone better than me to navigate the fundamental tension6 that government research needs to justify itself to taxpayers while paradigm-shifting work is incredibly hard to justify in advance.

However, there was one glimmer of hope among the government agencies. The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) has a shockingly consistent track record of shifting technologies people thought were impossible to being inevitable. It bears significant responsibility for the Internet, RNA vaccines, autonomous vehicles, and many other technologies that shaped today’s world.

Eventually I managed to convince myself that it might be possible to build a nonprofit research organization that riffed on the ARPA model. Then, putting on my tech hat, I got to work on making that possibility a reality, and here we are.

Today I’m finally ready to announce what I’ve been building: Speculative Technologies. We’re trying to create the world that has never been by running multi-year programs led by individual program managers with wide-ranging authority to coordinate several projects towards a single vision. We’ve structured it in an attempt to fill gaps left by other institutions: we prioritize functional systems over novel ideas so that the technology can get out into the world instead of ending up as a paper on a shelf.

One famous study found that only 2% of the social benefits of new innovations were captured by the firms that produced them. DARPA captured essentially no economic value from the innovations it created, but even if it had a 1% equity stake in every company that depends on the internet, it still would not have been profitable over its entire lifetime. Any company—least of all a basic research lab—does not and could not prevent idea spillover.

This’s why we’re a non-profit. So much impactful technology creation ends up having massive ‘positive externalities’ through idea spillover. Being a nonprofit breaks revenue-driven feedback loops. At the same time, it raises the very difficult question: “How do we become sustainable in the long run?”

Nevertheless, we think it’s the best path because of the size and potential impact of the unexplored design space we can open by asking not "What technology would create a great company?” but “What technology would create a great future?”

While our programs are not building products, we constantly consider what is going to happen after the program ends: what do we need to do so the technology can get out into the world and scale? We need to make technology sufficiently unspeculative to the point where it can continue in other institutions that have far more resources than we do—whether that’s as a startup, a government research program, or part of a larger company. Our job is to turn the impossible into the inevitable. Ambitiously, we’ll be able to do the same thing at some meta-level: proving that weird new institutions are critical for creating the world that has never been.

I’m excited to (hopefully!) spend the rest of my life creating a world where you can visit friends who live on the other side of the world for afternoon coffee, eat a Michelin-star meal created atom-by-atom in your kitchen, play basketball with your great-grandkids, and other possibilities we can’t yet imagine.

For more detail about Speculative Technologies, please check out our launch essay here.

A future that’s better than the present isn’t inevitable. Neither is our success. If our mission resonates with you, here is how you can help:

We rely on your support for now. You can join our funders club by donating small amounts here. If you’re interested in doing something bigger to support an existing program, work with us to create a new program, or support the organization as a whole, please shoot us an email!

If you or someone you know has a vision for a potential program, please send us a 1 page summary!

Share this essay to someone it might resonate with—as a small team, we depend on inbounds for both funding and ideas.

Stay in touch. We’ll be posting news updates, organizational learnings, and research results on Substack.

The fun technical term is an ‘actuator’—which effectively means a thing that enables a machine to interact with the physical world.

NASA loves acronyms so much they put acronyms inside their acronyms!

This may have involved claiming that I was proficient at C++ when my coding experience was exclusively grad student MATLAB and then spending the month between the interview and the job starting doing nothing but cramming, so that I was in retrospect telling a time-delayed truth.

For more about this see VC: An American History and Creative Capital

See: peer review, citation-dominated incentives, the committee-bound decisions, etc