Eleanor West & Marko Garlick write about New Zealand’s YIMBY movement for Issue 13. Read it online here.

Housing policy enthusiasts have been excited about New Zealand lately. Why? Because this small country at the bottom of the Pacific has recently passed some major upzoning reforms. Here’s what happened.

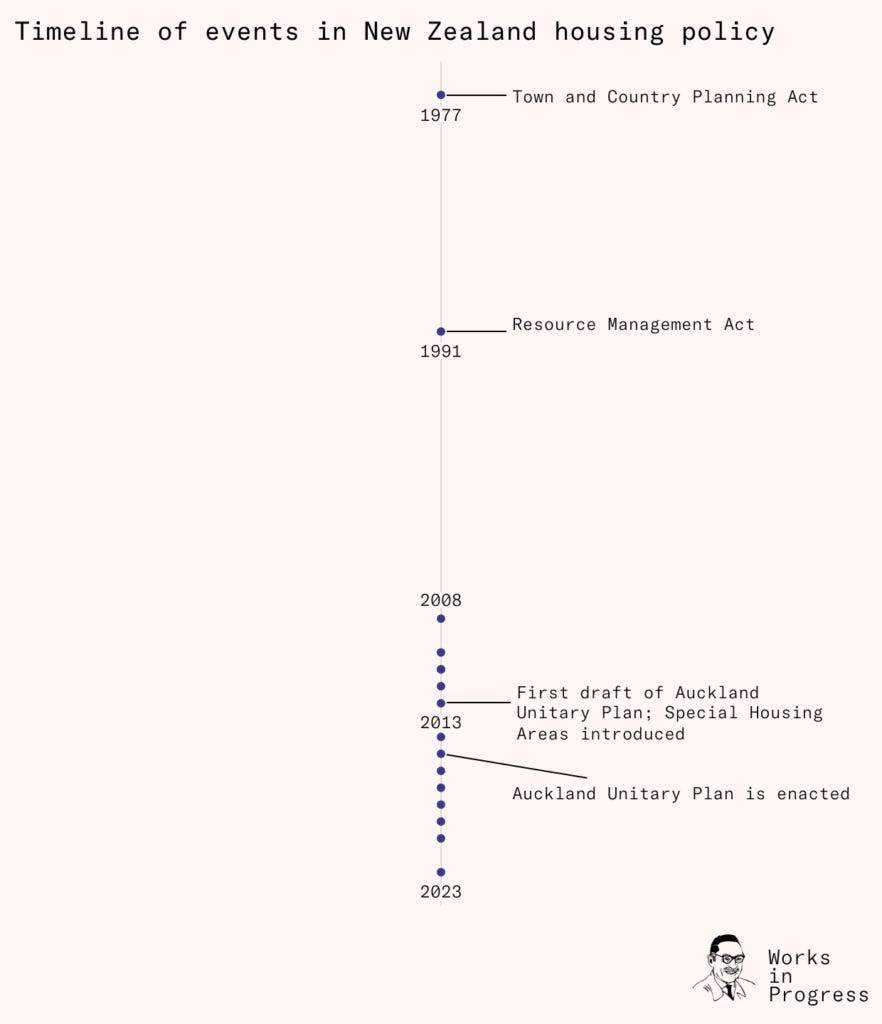

New Zealand faces one of the worst housing shortages in the world. As in many countries, this stems from local governments having the power to control development, but no incentive to encourage it. Since the 1970s, housebuilding in New Zealand has been tightly restricted. Consequently, in Auckland, the largest city, the house-price-to-income ratio had reached 10.8 by 2022. To put that in perspective, it was 8.7 in Greater London and 7.1 in New York.

If a central government wants local governments to enable building, it has two main options: carrot or stick. It can give local governments incentives to support development, or it can force them to zone for growth.

In recent years, New Zealand has been using some sticks. Major figures in the center-left Labour Party and the center-right National Party agree that the country desperately needs to build more houses. They’ve been united in their determination to change the system, even working together at times.

After a devastating earthquake in 2011, the National government required Christchurch to immediately zone for as much development as it had planned to permit over the next 30 years. Then, when Auckland Council wrote its zoning plan in 2016, the National government successfully pressured the local government to allow intensification across its non-historic suburbs by threatening to use their powers to overrule the council. And then in 2020, the Labour government forced the five largest cities to allow six-storey buildings within walking distance of city centers, commercial hubs, and existing and planned rapid transit stops.

But the biggest change came in 2021, when both major parties joined together to force local governments to allow three-storey townhouses in almost every neighborhood in the five largest cities – encompassing at least 57 percent of New Zealand’s population. But this may have been a step too far. Implementation of this most ambitious policy proved fraught, with some local governments strongly resisting the top-down directive. In the face of an upcoming election and the shifting sands of political incentives, the cross-party consensus broke down.

Perhaps the lesson is that a well-targeted stick can work on select areas. But in the absence of plentiful carrots for local government, it is too brittle a tool to use on the whole country all at once – in the end, the political consensus at the central government level was too fragile.

You can read the rest of the piece here.