From the vault: How the war on drunk driving was won

Deterrence alone might not stop crime. But, as the campaign against drunk driving shows, it could help create the norms that do.

Nick Cowen explains how the Western world conquered drunk driving through a combination of deterrence and changing norms for Issue 15. Read it online here.

My grandfather, an Essex doctor in general practice, was a pillar of his local community. An anxious and conscientious man, he was the kind of doctor who would visit unwell patients late into the night just to check their cases had not deteriorated into emergencies. His wife, my grandmother, was a magistrate.

He also would drink and drive on occasion, whether coming back from the opera or the golf club. After one night at Glyndebourne, he recalled watching other members of the audience, including other doctors, judges, professors, and journalists, stagger out to their cars, keys in hand, before clambering into the driver’s seats. I am guessing that his well-to-do friends seldom queried his capacity to drive.

My grandfather reduced, although did not quite eliminate, his drunk driving following one occasion when a police officer spotted him driving far too slowly home from one such event. He was pulled over and breathalyzed. He was certain he would be caught, but either the breathalyzer failed or he had metabolized just enough alcohol to be under the limit.

My grandfather dedicated his days (and many nights) to saving lives. But he also risked lives on his nights out.

Viewed from the 1960s it might have seemed like ending drunk driving would be impossible. Even in the 1980s, the movement seemed unlikely to succeed and many researchers questioned whether it constituted a social problem at all.

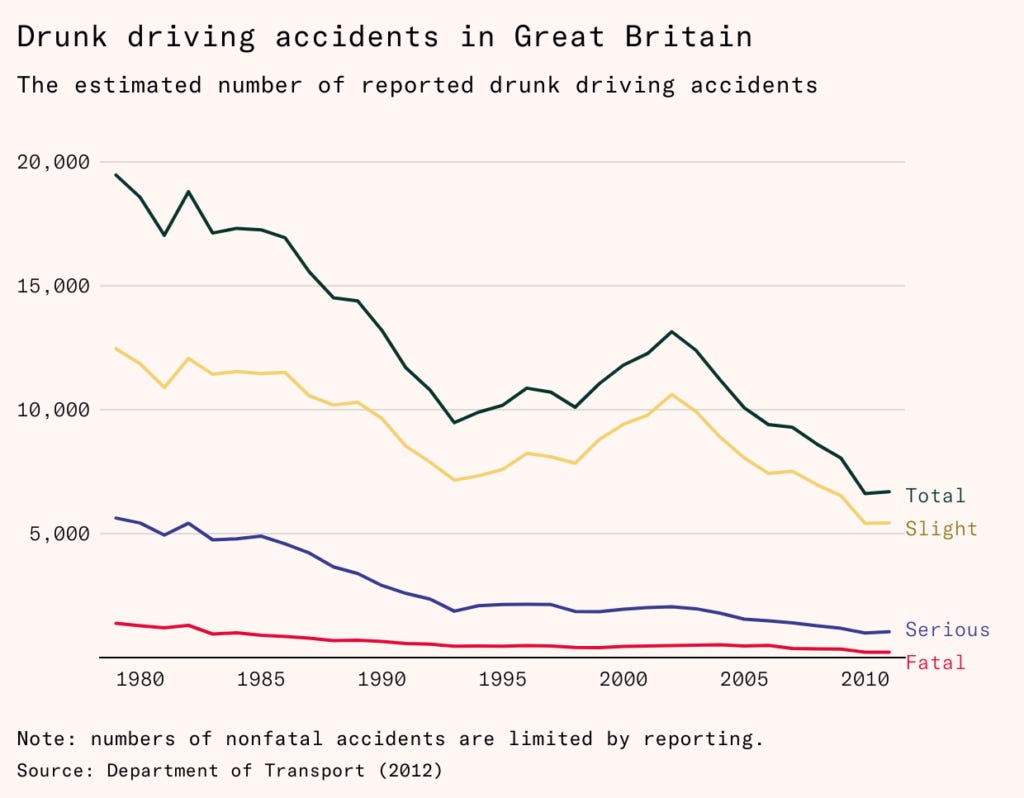

Yet things did change: in 1980, 1,450 fatalities were attributed to drunk driving accidents in the UK. In 2020, there were 220. Road deaths in general declined much more slowly, from around 6,000 in 1980 to 1,500 in 2020. Drunk driving fatalities dropped overall and as a percentage of all road deaths.

The same thing happened in the United States, though not to quite the same extent. In 1980, there were around 28,000 drunk driving deaths there, while in 2020, there were 11,654. Despite this progress, drunk driving remains a substantial public threat, comparable in scale to homicide (of which in 2020 there were 594 in Britain and 21,570 in America).

Of course, many things have happened in the last 40 years that contributed to this reduction. Vehicles are better designed to prioritize life preservation in the event of a collision. Emergency hospital care has improved so that people are more likely to survive serious injuries from car accidents. But, above all, driving while drunk has become stigmatized.

This stigma didn’t come from nowhere. Governments across the Western world, along with many civil society organizations, engaged in hard-hitting education campaigns about the risks of drunk driving. And they didn’t just talk. Tens of thousands of people faced criminal sanctions, and many were even put in jail.

Two underappreciated ideas stick out from this experience. First, deterrence works: incentives matter to offenders much more than many scholars found initially plausible. Second, the long-run impact that successful criminal justice interventions have is not primarily in rehabilitation, incapacitation, or even deterrence, but in altering the social norms around acceptable behavior.

The techniques used to drive down drunk driving help illustrate how many crimes were brought under control in the past, and how more might be in the future. Deterrence can jump-start a virtuous cycle: it reduces the rate of a crime, making the crime less normal. Less normal crimes bring higher community sanctions, or ‘moral costs’. This further reduces the rate at which people commit the crime, making it less normal still. This cycle cannot eliminate a crime entirely; some persistent offenders will continue to commit crimes unless they are incapacitated or rehabilitated successfully. But by using deterrence to create moral costs, we can make offenses rare, and focus enforcement efforts on the small group of those who commit crimes in spite of their costs.

You can read the rest of the piece here.