We released Issue 18 of Works in Progress last week. Do not miss out on our articles on the failure of the British land value tax; how to extend women’s fertility into their 40s; why the Hanseatic league rose and fell; prehistoric psychopaths; the technologies that made pineapples one of the world’s top fruits; why America builds 5-over-1s while China builds towers in parks; and the century-old steam network that heats and powers Manhattan.

Matt Clancy is the interim lead of Open Philanthropy’s new Abundance and Growth Fund, and the permanent lead of its Innovation Policy program. He also writes a living literature review on social science research about innovation.

Does technological progress really make us better off? Not just richer, or healthier, but happier and able to lead the kind of lives we want to?

You could try to adjudicate this debate with reference to psychological and sociological data on subjective well-being. You could look at the data on social media and depression, or loneliness, or climate change. That would all be worthwhile. But I’m going to do something different here. Rather than an impersonal investigation based on aggregated data, I’ll closely examine the lived experience of technological progress over the last forty years in the USA, looking at one particular case study I know very well: myself.

Looking at the evidence of my own life has downsides. Most obviously, it’s hard to draw any conclusions from a sample size of one. But the approach has one major offsetting virtue: I have views on what a good life looks like, and I can evaluate technological progress directly on those terms, rather than relying on proxies like health, income, or survey responses.

Better options

I think a good life has many components. Let’s walk through them.

A first component is the enjoyment of pleasures. For instance, I like the ambience of working in a coffee shop. Thanks to advances in computing, wifi, and the internet, I can spend a few hours a day working in them. That’s not an option I had growing up. Another thing I enjoy? Photography. Digital photography has improved my photo-taking skills and means I always have a good camera to hand. It’s also made it easy for me to look at the photos I’ve taken. My phone has access to practically every photo I’ve ever taken and algorithmically shows me something different from my life several times a day. Mostly pictures of my kids. Little pleasures, thanks to new technology.

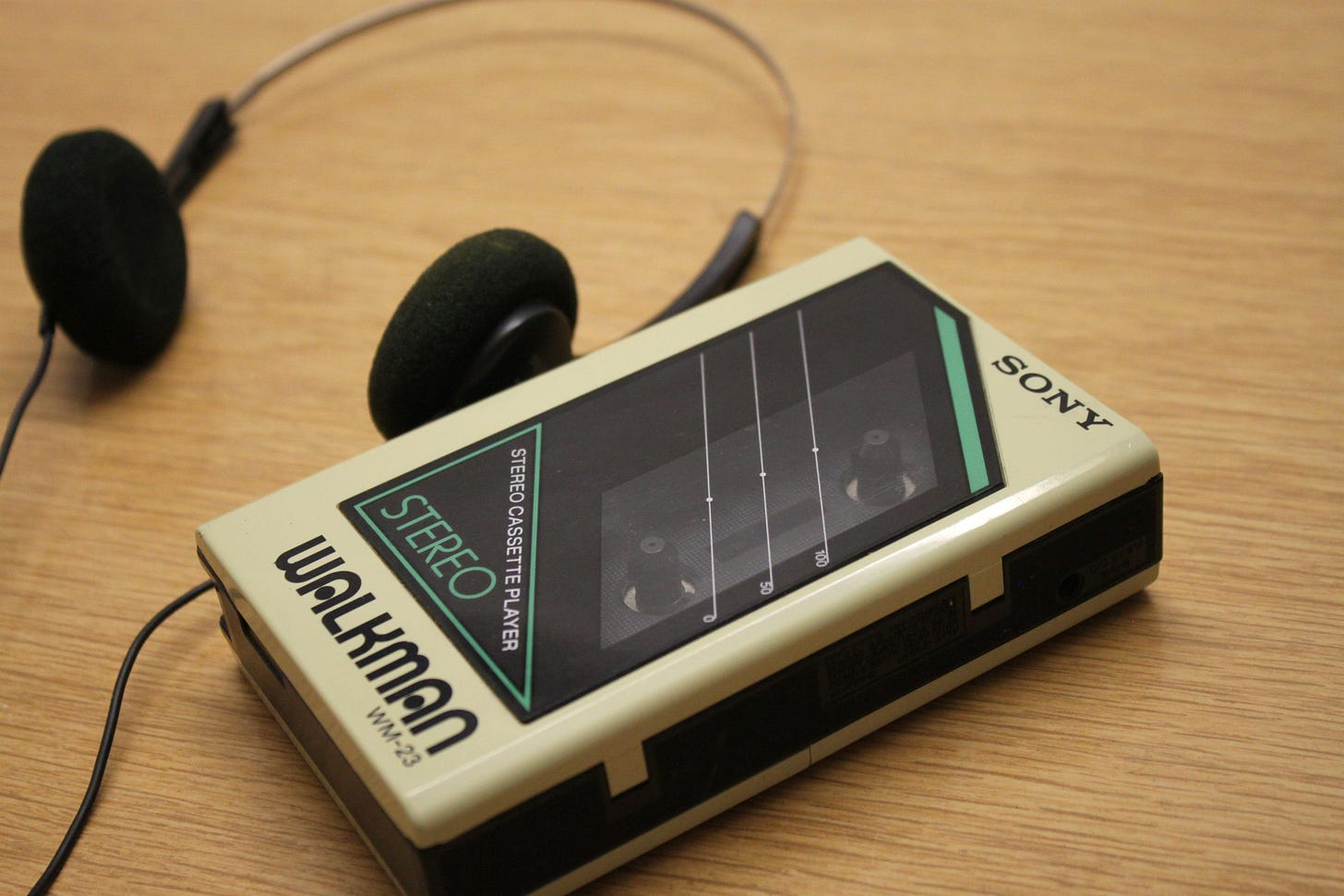

Technological progress has also radically improved my experience of some forms of art. I streamed more than one movie a week over the last year, and most of them were really good (I am working through BFI’s 2022 Sight and Sound poll). According to Spotify, I listened to roughly 55,000 minutes of music from more than 1,000 artists between January and mid-November 2024; that’s about 16 percent of my waking life during that interval! The diversity of choices, the quality of presentation, and the option to enjoy art like this at all odd hours, are all the fruits of myriad technological advances made during my life.

Enjoying pleasures is nice, but there’s a lot more to a good life. For me, another part of living well is learning about your world. Over my lifetime, there has been a revolution in our options for learning. To start at the most obvious level: there’s just more stuff to know than at any point in history. More science, history, stories, and ideas than ever. Available in more languages and from more perspectives. We’re way beyond what anyone can learn in a lifetime. Much of this new knowledge is a result of technological advances of all stripes; telescopes, large hadron colliders, gene sequencing, historical document digitization, statistical software, and more.

But beyond helping us discover more, technology has also vastly improved the mediums I use to take in ideas and analysis. The internet has enabled the flowering of a vast ecosystem of written explanations that tries to explain complicated material in an accessible way (think blogs, substacks, wikipedia, and the like). Large language models have expanded text-based options for explanation to an even higher degree. Beyond text, we’ve had a video revolution that is better suited for learning about some kinds of things (for me, film criticism and household repair). And it’s easier than ever to download, sort, and plot different kinds of data.

Going further, there have also been huge improvements in the ability to sift through this plethora of ideas. If I know exactly what I’m looking for, such as the title, author, or a specific quote, google can find that needle in the hay mountain. If my memory is hazy, large language models are a useful way in. And for the things I didn’t know I wanted to know about, the internet – or more specifically newsletters, blogs, twitter/X (though who knows for how much longer), and other curators – has exposed me to more ideas than anything available to me in the pre-internet world. Technological progress over the last few decades has dramatically improved my capacity to learn.

Another part of the good life, in my view, is being able to use your capabilities well, and to participate in work you find meaningful. Looking at myself, some of what I do in my job could have been done with the technology around at my birth (though I think at considerably more inconvenience). But a big part of my job for the last few years has been writing a living literature review, which is the kind of thing that became technologically feasible only during my lifetime. Lucky me: it turns out I am good at it, I enjoy it, and I believe it matters.

Moving on: our relationships with other people are another part of a good life. Technology has helped again here. Some of the connections I make with people are now mediated by digital technology, whether it is texting, tweeting, or talking over Zoom. No doubt meeting in person would be better, but sometimes that’s impossible, and these modes beat letter writing. Other times, technology actually enables me to have in-person meetings that might not otherwise have happened, especially with people who live far away. For example, I fly for work more than my father at this stage in his career (in part because progress means it takes fewer hours of work to pay for a flight). And in other ways, technology lets me have way more control over who I meet in person. I grew up in Iowa, and that’s where I live now, after moving away for work and school at several points in my life. My extended family lives here too. Because technology lets me work remotely, I can live among my extended family: I see them in person, and my work colleagues through digital technology, instead of the reverse.

So far, I’ve argued technological progress during my lifetime has allowed me to live a better life, in a non-superficial way, along several different dimensions: enjoying life’s pleasures, learning about the world, exercising my abilities, performing meaningful work, and connecting with other people. A final component of a good life, in my view, is acting morally. I’m much less sure that technology has given me better ‘options’ for moral living; I’m not even sure if that’s a coherent idea. But in my view, part of morality stems from curiosity about other people turning into sympathy and empathy for them, so that we want their lives to be better. To the extent that’s true, our ability to learn about other lives might mean our ability to act morally has indeed improved via technology.

More time

The other major way that technological progress during my life has contributed to better living is by giving me more time to use on the better things of life.

Lots of these advances are incremental things that are hard to get excited about. I steam frozen vegetables for my kids in a bag in the microwave now, instead of in a pot on the stove. That’s a few minutes less minding the pot and washing up. Most of my financial transactions are now contactless, which is a bit faster than a debit card or cash (and it means that I don’t have to go to an ATM). Cars are 15-30 percent more fuel efficient than when I first learned to drive which means a bit less time spent at gas stations. They need an oil change every 5,000 miles, instead of 3,000. Some of my electric home appliances like an electric snowblower and leaf blower don’t need maintenance at all. I’m sure there are lots of other conveniences too individually small for me to even notice. But they add up. All told, it’s easy for me to believe these little conveniences save me at least four minutes a day, which adds up to an extra day per year.

Other advances are more noticeable. Because I work remotely, I don’t drive to work anymore. Because of online shopping and delivery, I spend a lot less time driving to shops and picking stuff up, unless I positively want to do it. Many goods – movies, music, and audiobooks – are available instantly, over the internet. A lot of the most boring stuff is delivered my way via subscriptions now. All together, if I save an hour a day on commuting, shopping, and walking shop floors, that’s 15 days over a year, longer than many US company vacation policies, and all compressed into waking hours.

Those advances are particularly valuable, because the time saved can be used any way you like. But if technologies of convenience have freed up 15 days per year for me to do anything, other technologies have probably opened up as much time or more for a more limited set of options. Life is filled with all sorts of odd little moments, where it previously wasn’t possible to do much beyond think: waiting for a bus, for the kettle to boil, for the doctor to see you, for the checkout line to move, for the kids piano practice to end, etc. Thinking is great, but mobile phones, plus the internet, mean I have more options now. It’s a bit on me how well or poorly I spend this time, but I think I do alright using it to learn more about the world, in bite-sized pieces. Those moments add up, as anyone alarmed by the weekly report of how much time they spent on their phone can attest.

Technology helps me recapture odd moments and do more with them, but it also gives me more time by letting me double-spend time. For many years now, something like half of the books I have ‘read’ have been audiobooks that I listened to while doing something that would formerly have made reading impossible (such as walking, doing the dishes, or driving). Audiobooks have existed for a long time, but over my life various technologies have made them much more convenient to use. Slightly less important for me, but still a huge improvement on my options from two decades ago, are podcasts, which for me tend to feature in-depth interviews. I also use speech-to-text software to read me articles and websites where no recording exists.

And this continues to sell short the benefits of extra time. A lot of technology saves time to perform work tasks. In other words, technology also increases labor productivity. Workers don’t generally recapture that time for their own use, but it does mean they can sell their labor for a higher price. US median household income is up around 35 percent over my life, while GDP per capita has almost doubled. As it happens, my family’s income has grown by a roughly similar amount in recent years, so I have a pretty good sense of what this level of additional income feels like. Mostly, I think everything is a bit nicer, though we also buy more convenience (occasional babysitting and eating out) and security (we save more). Notably, most of what we spend the extra money on are technologies that were invented before I was born; but because of technological progress during my lifetime, we can afford more of it.

But there is one last way that technology gives us more time, and this one is the most salient of all: life-saving medical advances. I’ve been lucky enough to avoid serious medical issues in my life. For me, the medical advance that has probably most improved my personal life has been the covid-19 mRNA vaccines. But I have friends and family who’ve fought cancers, difficult births, heart attacks, blunt force trauma, and rare diseases. Many would likely be dead if medical progress had stopped at my birth. Over my life, the US life expectancy rose by at least three percent and when I think about my friends and family who survived medical problems that would have been fatal 40 years ago, that tracks.

Better living

Increasing options, more free time, and higher incomes complement one another. We have more time to spend how we want, and better things to spend it on. And the gains are not just trivial diversions either, but can be meaningful parts of a good life.

But maybe I am cherry picking. There are downsides to progress too. I think it’s possible that social media has made people less happy overall. The ability to shop, work, and get entertainment without leaving home probably contributes to rising loneliness. And in the future, maybe AI and robotics will replace a lot of labor and make it harder for people to find meaningful work.

This post isn’t the place to try and resolve those concerns. That’s a job for the aggregate statistics and academic studies, which I am avoiding here today. Restricting attention to the evidence under consideration in this post, my own life, I think the benefits of these technologies have (so far) outweighed the costs by a large margin.

I come away from this exercise pretty reassured that technological progress certainly has made my life better, in meaningful ways, even though the technology level when I was born was already pretty good. So much the better, I suspect, for people who start off in a worse place. But I think that raises another question: if technology does make our lives better, then why does it so often feel like it doesn’t? Why is this a question worth thinking about at all?

On the basis of this exercise, I’ll speculate that part of the answer is that the question is too big. If you ask me a smaller question about some specific technology I have no problem. Has the latest iPhone update made my life better? Sure, a bit. Has the mRNA vaccine? Very much so, on net. But as this post has helped to make clear, technological progress in our lives is the sum of thousands upon thousands of mostly little things. It’s just too much to get your head around and render a holistic judgment. If asked to render a judgment on all technological progress, I think we either think of lines on a graph, which are real but too abstract to feel in a visceral way, or we think of a handful of tangible technological improvements. But pick any few technologies at random (say, fuel efficient cars, streaming music, and zoom) and yeah they seem fine, but they don’t add up to much against the big things in our lives that we value. It’s only when you go through the effort of enumerating all the different technologies that come to mind, and write them down, that you can start to get a sense of the enormity of what technological progress delivers.