From the vault: The road from serfdom

Using opt-ins to reform Russia's backwards tsarist agricultural sector

Samuel Watling writes about Russian land reform for Issue 14. Read it online here.

Does improving institutions inevitably take a long time and involve conflict? Gains such as the establishment of democracy and the rule of law have often followed periods of prolonged and violent political conflict with existing power blocs. Yet it is theoretically possible to design institutional changes that buy in established interests using the gains from reform.

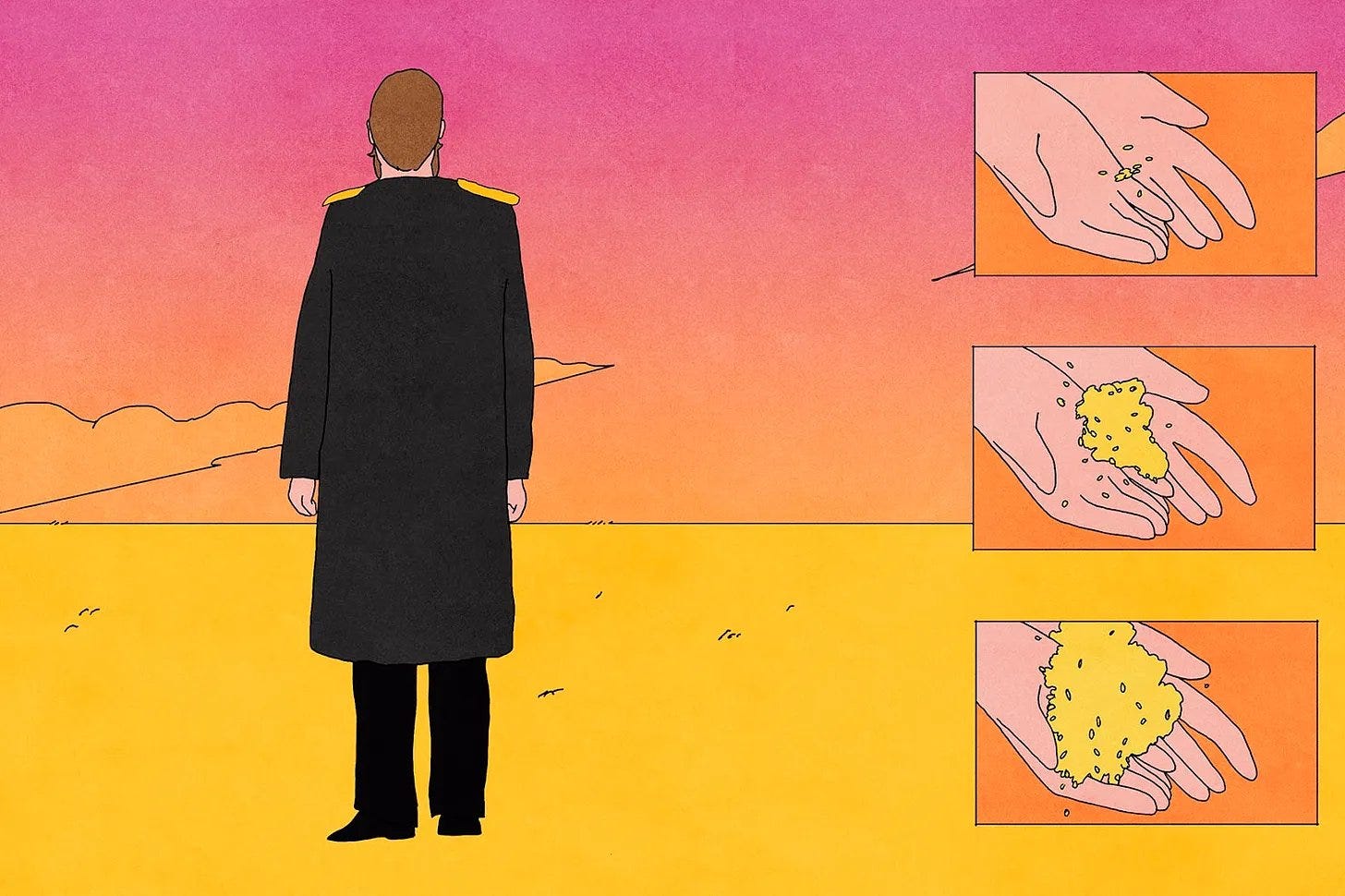

When the tsarist government of Russia nearly collapsed in the 1905 revolution, a last-ditch move to save it attempted to do just that. Unable to convince the tsar to politically enfranchise the impoverished peasantry, the prime minister, Pyotr Stolypin, tried to empower them economically instead.

He did this by allowing peasants to break up the peasant commune – a dysfunctional legacy of serfdom, abolished just 44 years earlier, that held agricultural land as a collective – thereby establishing individual property rights. It was too late to save Russia from revolution, but it did begin one of the most successful economic reforms in history.

How institutions develop

The consensus in modern institutional literature, most famously in the writings of Douglass North or Daron Acemoglu, is that the political institutions that best encourage long-term economic growth are liberal democracies with clearly defined private property rights.

Even if we accept this, it still presents countries wishing to grow with a problem. They do not simply choose their political institutions off the rack; institutions develop over time within the constraints of the existing system. In the modern era, some countries – mostly in Western Europe, East Asia, and North America – have been lucky. Over the past five centuries, they entered a benevolent and mutually reinforcing cycle in which good institutions enabled economic growth, which in turn allowed for more investment into state capacity, providing further incentives for reform.

Yet the challenge of traveling from one path – of poor institutions and autocracy – to a better one is not straightforward. The development of liberal institutions in the West took centuries and involved significant violence. We cannot simply wait several lifespans for change to come.

We now know that coercive or extractive institutions such as slavery and autocracy have negative social implications that last for centuries. Yet successful reform away from these kinds of practices has always met significant opposition. Even knowing that there are better institutional arrangements does not mean that those who can enact change believe it is in their immediate interest to do so.

The challenge for individual reformers is to reform suboptimal institutions in a way that sticks, to do it quickly, and to avoid a violent or successful backlash. This article will explore an often-forgotten set of institutional reforms that aimed to do all of that. The attempt by one visionary reformer in tsarist Russia to give the majority of its citizens property rights may offer us useful pointers for institutional reform today.

You can read the rest of the piece here.