From the vault: The future of silk

Silk is stronger than steel or kevlar. What could it be used for?

Today is the last day to apply to Invisible College, a week-long residential seminar hosted by Works in Progress to give people aged 18–22 a grounding in the topics most important to us: how the world got rich, what is going wrong with science today, and the political economy of housing, urbanism, and cities.

The invention of the hypodermic needle in 1844 brought major benefits to the practice of medicine, but ran headlong into an unexpected quirk of human nature. It turns out that millions of people feel an instinctive horror at the thought of receiving an injection – at least ten percent of the US adult population and 25 percent of children, according to one estimate. This common phobia partly explains the widespread reluctance to receive vaccinations against Covid-19, a reluctance which has led to tens of thousands of unnecessary deaths.

But a company in Cambridge, Massachusetts, called Vaxess Technologies plans to sidestep this common fear by abandoning stainless steel needles and switching to silk.

Vaxess is testing a skin patch covered in dozens of microneedles made of silk protein and infused with influenza vaccine. Each needle is barely visible to the naked eye and just long enough to pierce the outer layer of skin. A user sticks the patch on his arm, waits five minutes, then throws it away. Left behind are the silk microneedles, which painlessly dissolve over the next two weeks, releasing the vaccine all the while.

The silk protein acts as a preservative, so there’s no need to keep it on ice at a doctor’s office. ‘It’s similar to what happens when you freeze something,’ said Vaxess founder and chief executive Michael Schrader. ‘It’s room-temperature freezing.’ In testing, Vaxess found that flu vaccines stored in a silk patch at room temperature remained viable three years later.

No more need for a ‘cold chain’, the costly network of refrigerators between manufacturing plants and medical clinics required by so many vaccines. Indeed, there’d be no need to get vaccinated at a clinic at all. Patients could vaccinate themselves.

‘We would mail you a patch,’ said Schrader. ‘It looks like a nicotine patch, only much smaller. You wear the patch for five minutes, then take it off and throw it away.’

Having completed a successful phase one clinical trial of the silk patches in late 2022, Schrader hopes to bring them to market by 2028.

It’s hardly the sort of product we’d usually associate with silk, the tough, luxurious, and luminous fabric that has delighted people for at least 5,000 years. But silk is proving to be far more valuable than its early Chinese cultivators could have imagined.

Much of what we now understand about silk was discovered at Silklab, a branch of the department of engineering at Tufts University in Medford, a suburb of Boston. Here a visitor encounters silken lenses that project words and images when bathed in laser light; surgical gloves coated in silk that display a warning if they’ve been contaminated with pathogens; tiny silken screws that are strong enough to repair a broken bone, only to dissolve entirely once the injury is healed.

For Silklab director Fiorenzo Omenetto, silk is not a fashion statement. It’s a set of microscopic Lego blocks that he and his colleagues are pulling apart and reassembling into an array of unexpected products.

‘We make everything,’ said Omenetto. ‘We make plastics, we make edible electronics, we make coatings for food.’

Silk isn’t everything at Silklab. Omenetto and his colleagues experiment with a variety of similar molecules, known as structural proteins. They’re found all over the place, shaping and strengthening plant and animal tissues. There’s the keratin in hair, collagen that holds our organs together, and more.

But for Omenetto, silk comes first. And his team has found an array of new uses for a fiber that humans have been cultivating for millennia.

Legend has it that the wife of the Yellow Emperor, who reigned around 2700 BC, was sipping hot tea under a mulberry tree when the cocoon of a silkworm fell into her cup. The hot liquid dissolved the cocoon’s sticky coating and caused the silk underneath to unravel, revealing its extraordinary beauty and strength. Then again, Chinese archeologists in 2017 found traces of silk in the soil under bodies in tombs 8,500 years old. The traces could be wild silk, but they could also suggest that sericulture – silk farming – may have begun much earlier.

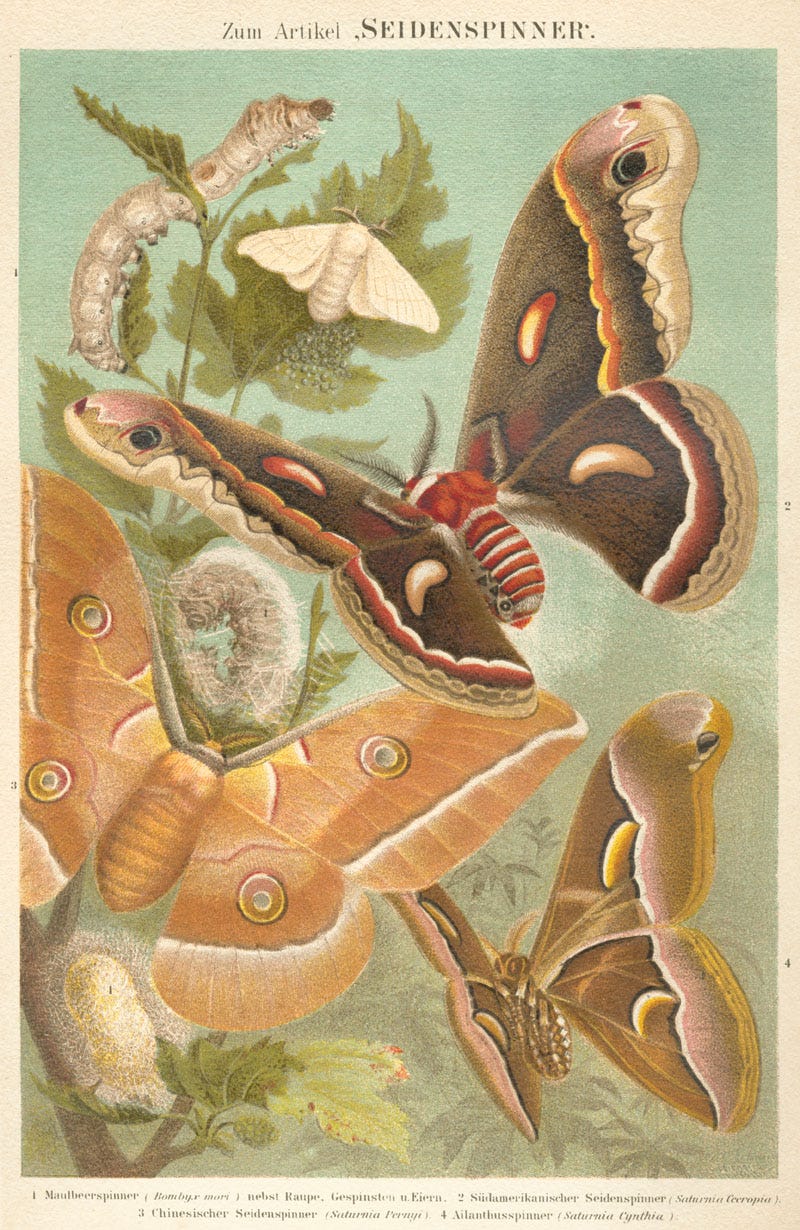

A gray moth called Bombyx mori is the source of the silk. Centuries of selective breeding have created moths that reproduce at an exceptional rate – up to eight generations per year, compared to just three for wild silk moths. Domestication has wrought other changes; their wings are so stubby that the moths can barely fly, and the female moths are born already fat with as many as 500 eggs ready for immediate fertilization by a male.

You can read the rest of the article here.

This article first appeared in Issue 14 of Works in Progress.

Hiawatha Bray is a technology columnist for The Boston Globe and author of You Are Here: From the Compass to GPS, the History and Future of How We Find Ourselves. Follow him on Twitter.