Read the latest issue of Works in Progress here.

Why do psychiatric conditions exist?

This question is both unsatisfyingly unanswered and incredibly important. Here we will consider some features of the over-century-long failure of psychiatry to explain mental disorders, before reviewing a theoretical framework which promises to explain these conditions in a way which is not only scientifically sound, but emancipating. The framework in question is evolutionary psychiatry, and its principle thinking is simple: if we use evolutionary theory to explain biology, then we should be using evolutionary theory to explain psychiatric disorder. If evolution was given proper attention and integrated into mainstream psychiatry, we would usher in a new era of understanding and treatment of psychiatric conditions.

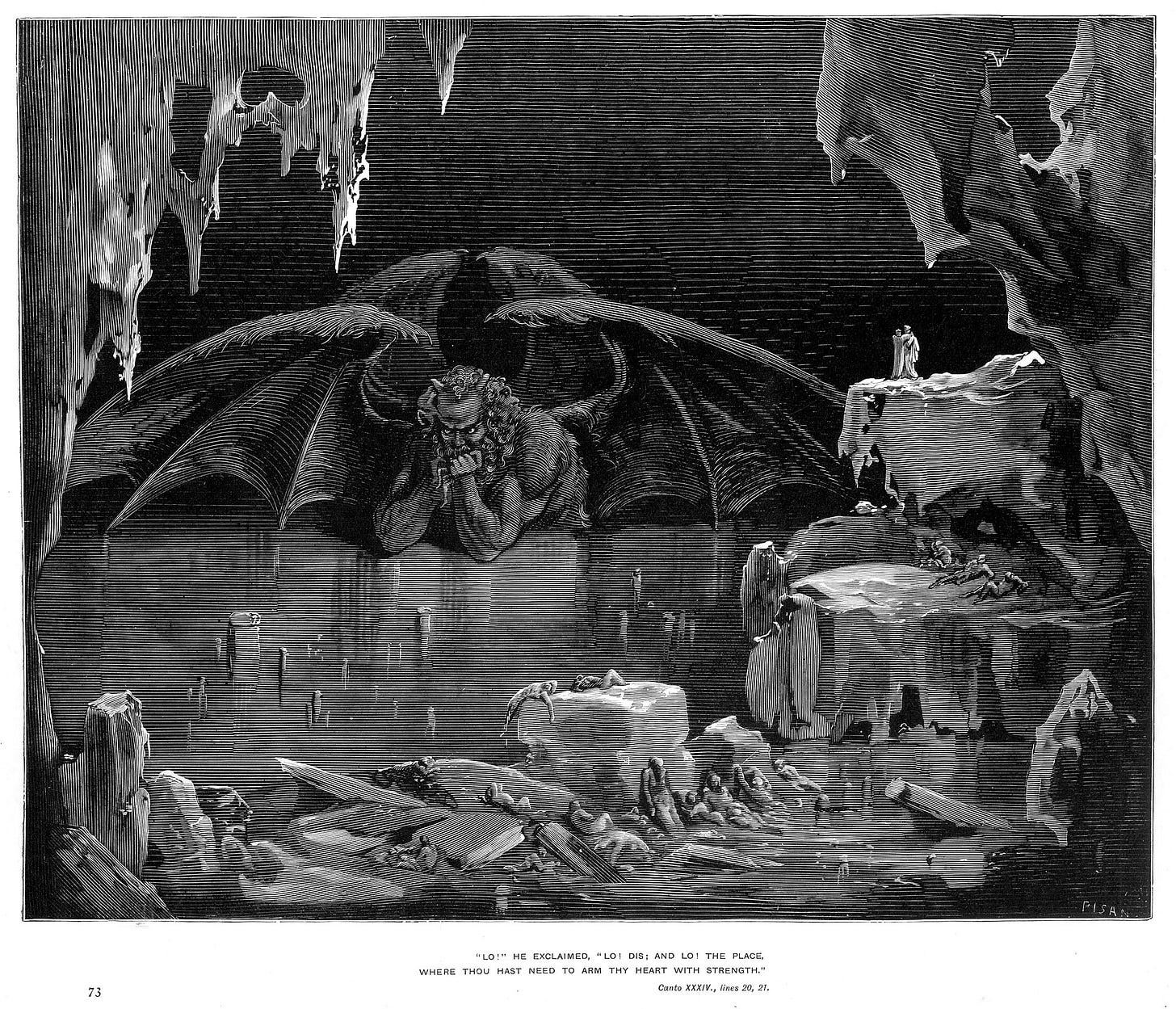

Psychiatry is a practice with more than a checkered past, perpetrating horrors even in living memory: Sprees of lobotomizing adults and children; purposefully inducing comas in schizophrenics, producing thrashing, spasming and salivating so bad that one psychiatrist reported the scene on a ward as alike to artist Gustave Dore’s depictions of hell; and the widespread demonization of homosexuality justifying the electrocution and injection of homosexuals with nauseating drugs during slideshows of sexually attractive individuals of the same sex, hoping to train them into being sick at their own sexuality.

Advances in treatment over the decades have come more from the dismissal of old and harmful practices than the inception of new ones. As electrocution and nauseation were slowly recognized as both immoral and ineffective, we are now left with psychotherapies and pharmaceuticals of unreliable and underwhelming efficacy. Tens of billions of dollars and several decades of research have led to few new discoveries. Many drug developers have now left psychiatry for more easily understood and chemically pliable conditions of the body rather than the mind. Leaders in national mental health research have expressed dismay that so little progress has been made. Some research suggests that the burden of psychiatric illness might even be worsening, not lessening.

Psychiatric therapies have never been atheoretical – psychiatrists have always justified their treatments with some school of thought: Freudian psychodynamic theories placed blame on early childhood and subconscious urges; behaviorism justified the application of pain to try and train people out of wrongthink; and more recently, chemical imbalance theories were used to advertise pharmaceuticals, despite the narrative of simple dopamine and serotonin dysfunctions having been long dismissed in academic circles. Recent advances in genetics and neuroscience have provided more evidence and complexity, but no promising new theories. Psychiatry today can be considered a discipline in crisis, surviving only because psychological and pharmaceutical treatments are effective for some people, some of the time, and so we still need them. The way is open for a new paradigm in psychiatric theorizing.

You can read the rest of the piece here.

This article first appeared in Issue 01 of Works in Progress.

Adam Hunt is Postdoctoral Researcher at the University of Cambridge