From the vault: The entrepreneurial state

How state competition – through war – can drive institutional progress

David Schönholzer writes about state development for Issue 13. Read it online here.

One of the most fundamental facts of life is that where you are born is a huge determinant of how your life will turn out. Someone’s chance of leading an economically secure life is vastly higher if they happen to be born in Zurich, Seattle, or Kyoto rather than Mumbai, Nairobi, or Caracas.

But why are some places much better at providing an environment for the development and adoption of technology than others? Much of the divergence between rich and poor places can be traced back in time to the emergence of a set of institutions in Europe, which have partially spread around the world. Northwestern Europe was already substantially richer than other world regions well before the Industrial Revolution, but there is an ongoing debate in economic history on the reasons for Europe’s divergence from the rest of the world.

While geography and culture have likely played some role, as well as expropriation through colonialism, the nature and the development of the state is the most important factor behind economic fortunes. ‘Little else is requisite to carry a state to the highest degree of opulence from the lowest barbarism, but peace, easy taxes, and a tolerable administration of justice: all the rest being brought about by the natural course of things’, wrote Adam Smith back in 1755.

He was right. Secure property rights and a limited state monopoly on violence have withstood the test of time (although after the experience of the twentieth century we may add a welfare state to this list). This stability fostered the investment and invention that drove living standards higher.

In striking contrast to Smith’s peace as an essential ingredient for states to foster prosperity, however, one popular explanation comes from Charles Tilly, who stressed the centrality of war as a driver of state formation: ‘War made the state, and the state made war’. After all, since 1400, more than 1,000 wars have taken place in Europe, with millions of casualties and thousands of leveled towns.

Why would war, an inherently destructive activity, foster development? One story sees wars as the bitter ‘Gifts of Mars’ that helped to propel Europe to early riches by decimating its population and thereby increasing each surviving farmer’s land available for cultivation. Another claims the constant threat of war drove farming households to seek refuge in walled cities, leading to urban growth, and in turn to development.

Even put together, these explanations cannot be complete, since they imply more war is always good. The benefits of war came, of course, at an enormous cost: as well as the deaths of countless soldiers and peasants, European wars also cut short the lives of future inventors, engineers, and statesmen who might otherwise have driven technological progress more quickly. (To give one example, the astronomer William Gascoigne, inventor of the telescopic sight, was killed at the age of 32 at Marston Moor during the English Civil War.) And they ruined prosperous cities that would have served as nexuses of trade and progress. Any explanation for the emergence of wealth that relies on conflict needs to generate a sufficiently big benefit to counterbalance this.

War acting as a selection mechanism for more effective states might provide this counterbalance. While wars had costs, more effective states tended to win out from them, leading to a virtuous cycle of more effective institutions.

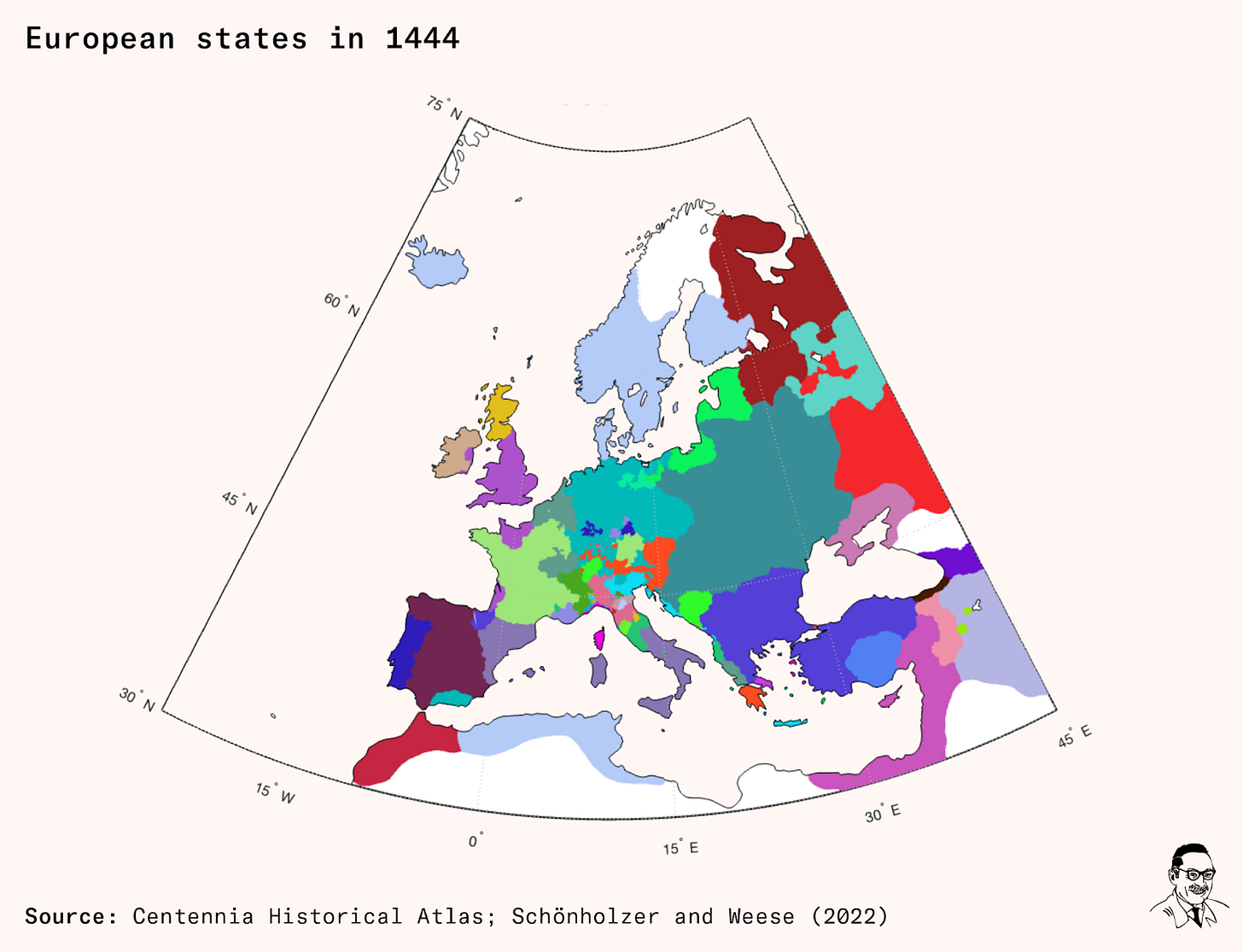

The death and birth of states through European history

New research conducted by Eric Weese and myself explains how competition, including through war, led to creative destruction among European states. We use the newly available research edition of the Centennia Historical Atlas, which collects thousands of historical maps in the largest and most accurate database on historical state boundaries in the world. Each year between the years 1000 and 2002 has ten maps – a total of more than 10,000 maps – showing the exact borders of every state in Europe, Western Eurasia, the Levant, and North Africa. When territory changes hands from one state to another in between maps, it may be the result of a war, inheritance, or treaty.

These maps have been painstakingly assembled and digitized over the course of decades by Frank Reed at Clockwork Mapping, opening up an entirely new avenue for research in economic and political history. We vetted the data with the help of two economic historians, whose accounts of individual cities matched the data closely. While some states had less control over their territory than others and some borders were more porous than others, it gives us the best view of ‘boots on the ground’ – de facto control by states – of every acre of land in Europe since the Middle Ages.

We combine these maps with data on the populations of 2,206 European cities between 800 and 1850. A successful state grows its cities’ populations by attracting immigrants from other states; by preventing deaths from war, disease, and poverty; by seeing more births; and through internal immigration.

So how did territorial competition affect states according to this data? Among states with at least one city, the average state survived less than a century. The radical Anabaptist Christian Münster Republic existed for just over a year between 1534 and 1535, before its rebellion was crushed by a confederation of local nobles and the city’s prince-bishop. Revolutionaries overthrew the Prince-Bishopric of Liège in 1789, at the same time as the French Revolution, but the Republic of Liège that they founded was destroyed by a joint Prussian-Austrian invasion two years later. Still, it outlasted the neighboring United Belgian States, which lasted for just one year, between January and December 1790, before its former Austrian rulers crushed the new state and regained control over the territory.

These states did not last in the ruthless market for governance, but their ‘deaths’ were matched by an inflow of ‘newborn’ and expanded states that arose out of the remnants of their forebears – the return of the Prince-Bishopric of Münster and Liège, or the restoration of Austrian imperial rule.

This steady churn was accentuated by periods of mass extinction of states, such as when Napoleon swept the German lands after the French Revolution with his iron broom (including both the Prince-Bishopric of Liège and Austrian rule in Belgium). But even putting these periods aside, the European state system was constantly in flux throughout the entire period between 1000 and 1850.

You can read the rest of the piece here.