Ten favorites from 2025

Some of the Works in Progress essays that I enjoyed the most this year.

Thanks for reading Works in Progress this year. As well as launching our new print edition and some podcasts, we published forty three articles. I am proud of all of them, but here are ten of my personal favorites from the year.

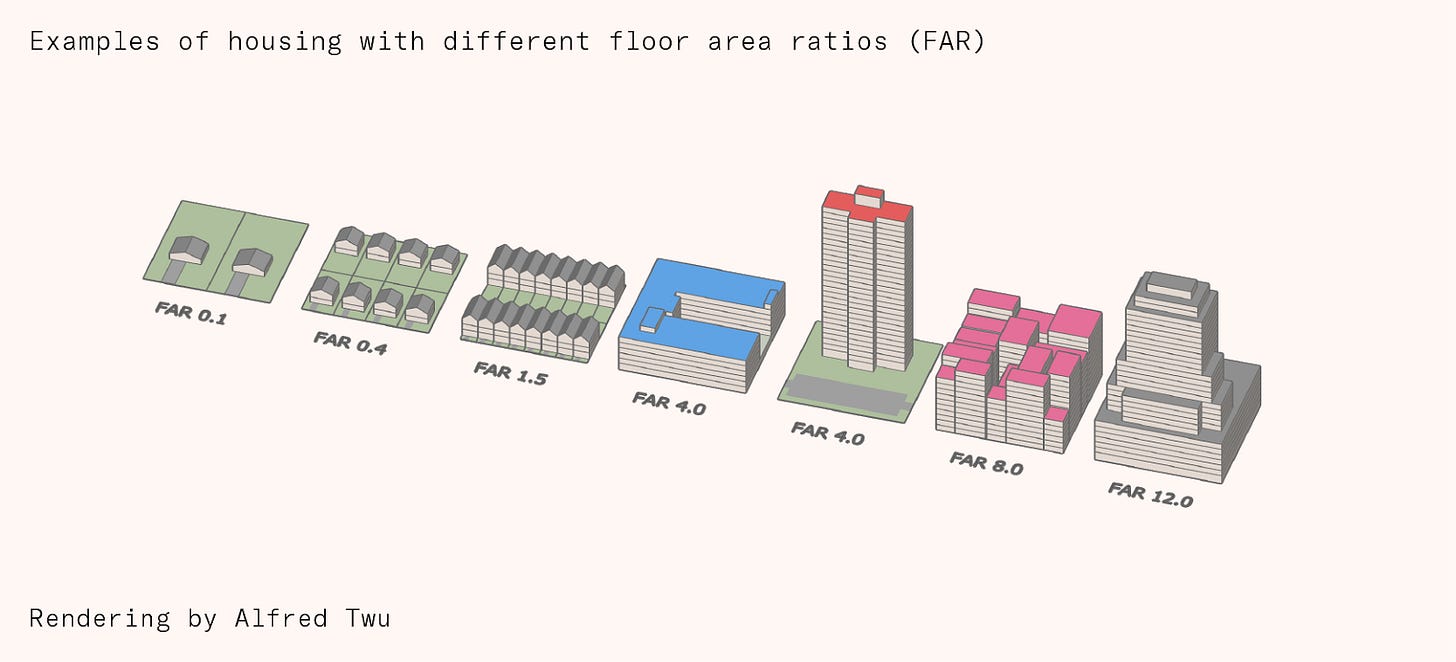

Chinese towers and American blocks by Alfred Twu. I learned a lot from this about the differences between American and Chinese urban forms. The arcology-like xiaoqu tower blocks that China is famous for are not, it seems, merely a product of Chinese cultural preferences, but strict regulations about how much sunlight apartment blocks must get. And their floor area ratios are not much different to much shorter and squatter 5-over-1s that are becoming ubiquitous in newer American developments. I was also interested to learn that 5-over-1s get their name not from being five floors of residential over one floor of commercial units, but in reference to the US building code, which classifies wood frames as Type V and concrete floors at Type I (5-over-1s were originally built with wooden frames over a concrete car park).

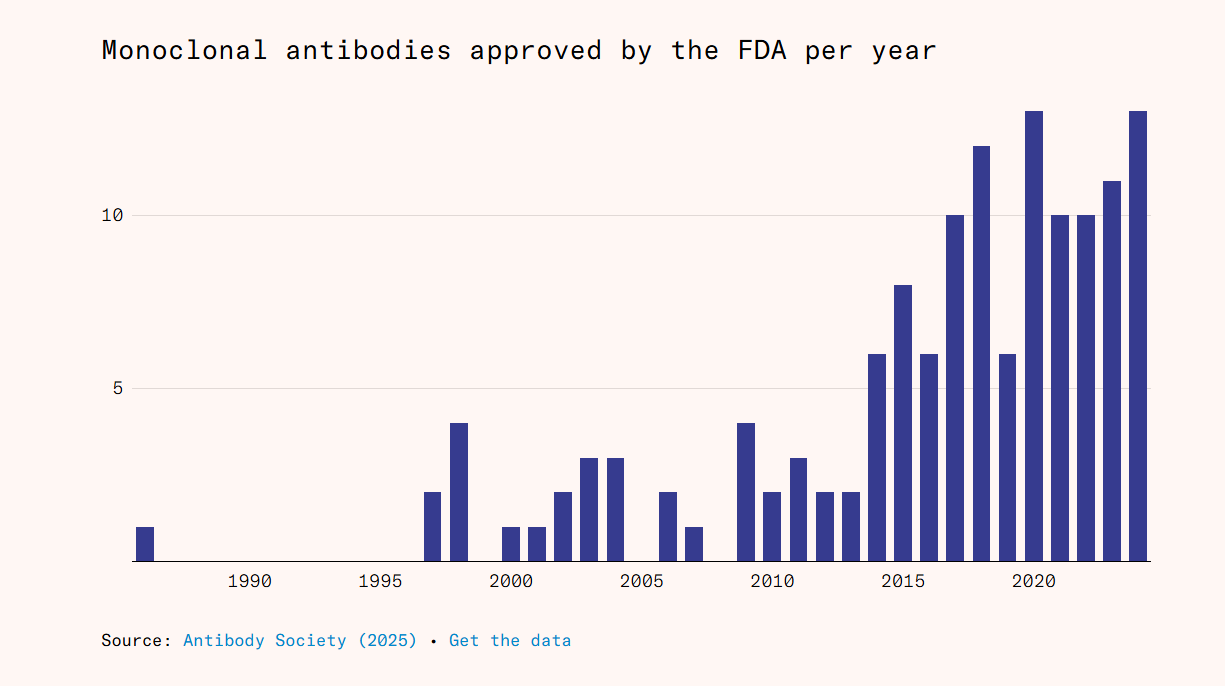

How to make an antibody by Alex Telford. Antibody treatments have only really matured over the past ten years or so, but have exploded in popularity. Four of the world’s ten best-selling drugs are monoclonal antibody treatments, including the biggest drug by revenue: Keytruda, used to treat solid tumors, which has been used to treat 2.5 million people so far. We seem to just be skimming the surface with what we’ve got, and Alex sketches out how we might be able to scale up these treatments to treat everything from malaria to influenza to snakebites.

The rise and fall of the Hanseatic League by Agree Ahmed. This is a cool piece for two reasons. One, this late medieval / early modern period of European history is absolutely fascinating, and the story of the Hansa is in many ways the key economic and technological history story of Northern Europe in that period. Bigger boats allowed merchants to meet new demand for wool driven by the invention of the horizontal loom, which tripled a weaver’s output, and bring Swedish freeze-dried fish to feed towns that were beginning to deplete their own fish stocks (fish accounted for 10-20 percent of food spending at this time). The Hansa only really declined after the Dutch developed technologies that outdid them. Two, it’s a history of successful coalition building and maintenance, reliant on mutual favors and reputation more than force, which interests me well beyond this historical case.

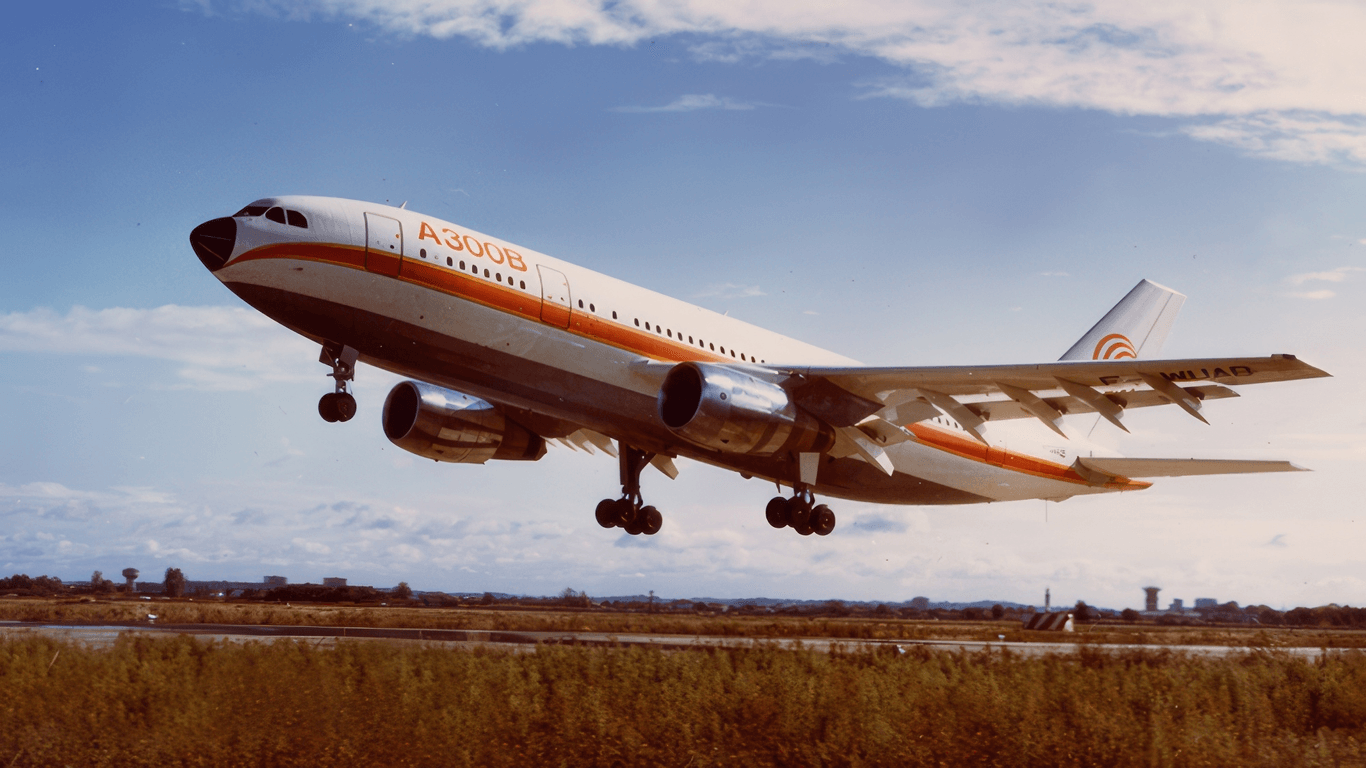

How Airbus took off by Alex Chalmers. Considering how dismal a lot of European attempts at industrial policy have been, it’s pretty fascinating how good Airbus is. Somehow, a high-tech venture backed by the French, German, British, Spanish and Dutch governments has managed to become the biggest aerospace company in the world, with an excellent safety record and comfortable planes for passengers. It’s not really clear how replicable that success is, since so much of what Airbus did goes against what people tend to want from industrial policy today (it focused hugely on its customers, rather than its suppliers), but it’s still very interesting to understand how these sorts of projects can succeed.

The merits of unified ownership by Samuel Hughes and How to redraw a city by Anya Martin. Samuel points out that many of the nicest older parts of cities like London were built while being owned by a single entity. This meant that it could be profitable to have pretty, coherent designs across the area, and could provide public spaces like parks and capture the benefits via higher land values overall. We are unlikely to ever go back to this model now that ownership has been fragmented, but we might be able to devise mechanisms that approximate it. ‘Land readjustment’ is a mechanism in Japan that does something like that: it allows landowners to collectively decide to redraw the boundaries of their plots and sell off a portion of them to allow and profit from things like new infrastructure projects. It’s a way to get around holdout problems without just expropriating people’s land (which is costly and politically impractical), and seems to do a good job of facilitating new development.

Liberté, égalité, radioactivité by Alex Chalmers. The French state-run energy company EDF managed to build forty nuclear reactors in the space of a decade, quite affordably, and today about two-thirds of France’s electricity comes from nuclear power. I think that’s pretty extraordinary, because it suggests that there isn’t really any technological reason other Western countries can’t do the same today, it’s a question of getting the politics right. This article shows how much of France’s nuclear program actually was about politics, especially things like local votes and bribes incentives to persuade towns to accept nuclear plants near them.

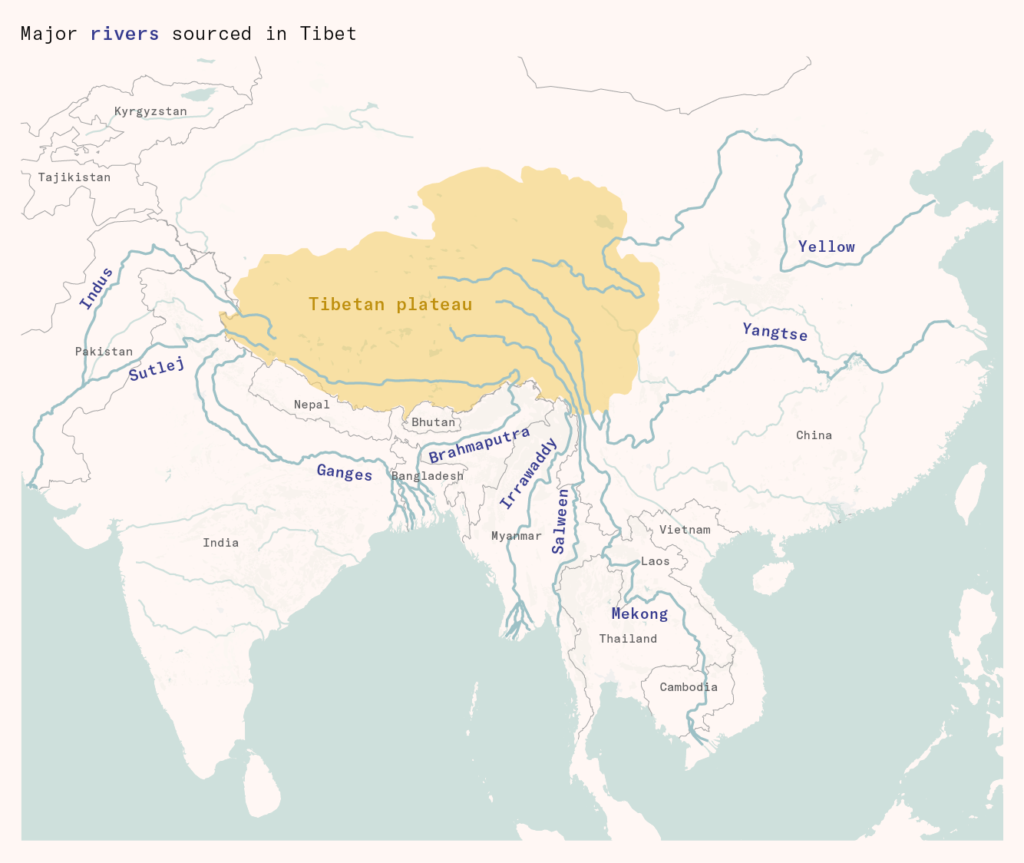

Rivers are now battlefields by Connor Tabarrok. Controlling the Tibetan plateau means controlling the water sources of about two billion people. Control of this kind is particularly easy because of how mountainous Tibet is (making dams easier to build) and because three of the biggest rivers, the Mekong, Salween and Yangtse rivers, flow together very closely in a choke point that would make diverting the first two into the Yangtse quite easy. Hydroelectricity is already a gigantic power source in China: 13 percent of China’s electricity comes from it, or 1,300 terawatt hours, roughly equivalent to the output of all US coal and renewables combined. Connor suggests that desalination could be a way to reduce downstream countries’ vulnerability to this, and that this could be an area where cheap solar power is especially useful, since desalination is extremely energy-intensive.

How to spot a monopoly by Brian Albrecht. Competition policy is an amazingly important part of economic regulation, not least because of the damage that can come from doing it badly. It is distressing to dig into it and learn how much of it is built on sand: economic analysis that no sane person would base any important decisions in their own lives on, but that major economies still regularly base important economic interventions on. Brian proposes a measure of competition that has far fewer of the downsides of the conventional measures used (like concentration or profit levels), which is to look at whether the most productive companies in a market are growing their market share or remaining static. What’s cool about this one is that the recommendation can be picked up today by competition regulators and statistics agencies, at very little cost: just start collecting this data more rigorously and seeing if it fits with other things we expect to see from more and less competitive markets.

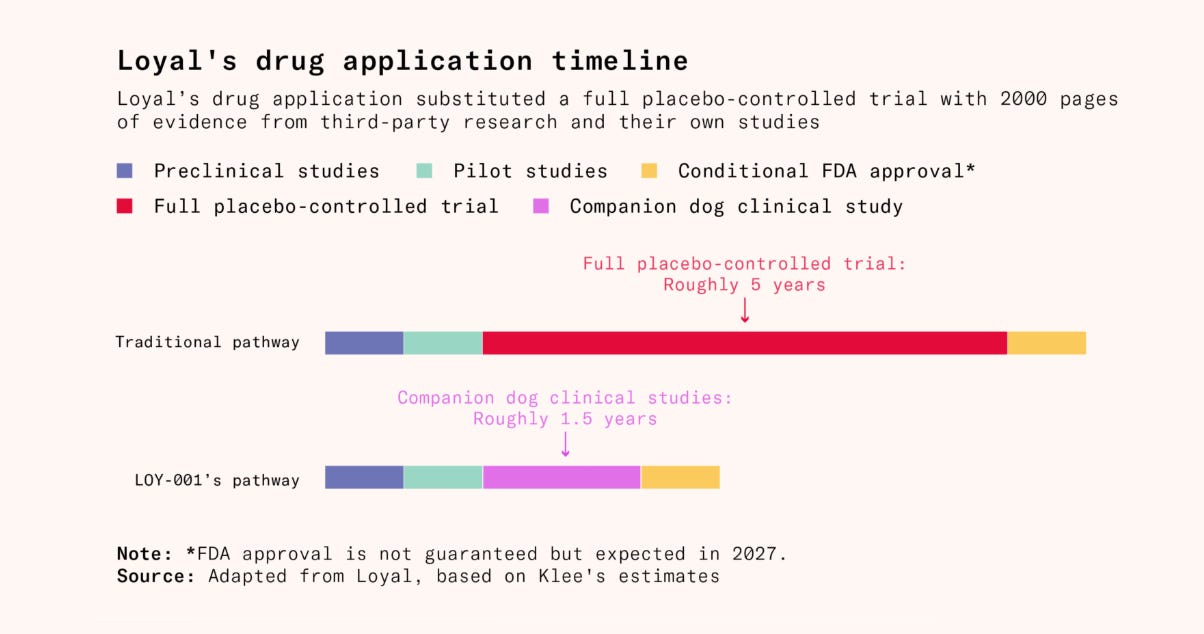

The secret fast track for animal drugs by Trevor Klee. Everyone reading this will know about how slow and ponderous the FDA can be in trialling and approving new human drugs. So it is quite a surprise to learn that for animal drugs the FDA has become, since 2018, something quite a lot better. Animal drugs have to be shown to be safe, shelf-stable, and to have some promise of working, but do not have to be proven to be efficacious the way human drugs do, and this has made it much faster to get drugs that do end up doing a lot of good into people’s hands (and their pets). Perhaps something similar would work for some human drugs too.

Thanks for reading this year, and have a happy new year.

— Sam Bowman, editor.

I love this newsletter, but fyi the link to the article on the Hanseatic League doesn't work. I missed it and would love to read it!

Thanks a lot!