Notes on Progress is a new diary-style format from Works in Progress, where some of our writers give a personal perspective on the work they’re doing and some of the questions they’re grappling with. This is an experiment, so let us know what you think as we send these out over the next few months. If you only want to hear when we have a new issue, you can opt out of Notes in Progress here.

Here, William Buckner writes about the display of human remains in museums. If you enjoy this issue, please share it on social media or by forwarding it to anyone else you think might find it interesting.

In his 2012 book Headhunting and the Body in Iron Age Europe, archaeologist Ian Armit describes visiting the Musée Canadien des Civilisations in Quebec. Armit writes of the “spectacular displays,” which “have been assembled with the close and active involvement of the various First Nations communities.” He notes some particular highlights, such as full-scale reconstructions of house fronts from the Canadian Northwest Coast, monumental carved house poles, and extensive material on potlatch feasts.

“Yet something is missing,” he says, “When I visited, I was surprised by the lack of information of indigenous ritual practice, social inequality, or conflict.” Armit goes on to discuss practices of slavery and human sacrifice that were prevalent across the Northwest Coast (and elsewhere around the world). “It gives one a rather different perspective on the monumental carved Nuxalk house poles to realise that their erection was often accompanied by the ritual sacrifice of a slave,” he writes.

I’ve thought about Armit’s perspective quite a bit since I read it back around 2017 or so. I thought it of it more recently in 2020 when the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford removed its collection of tsantsa from public display.

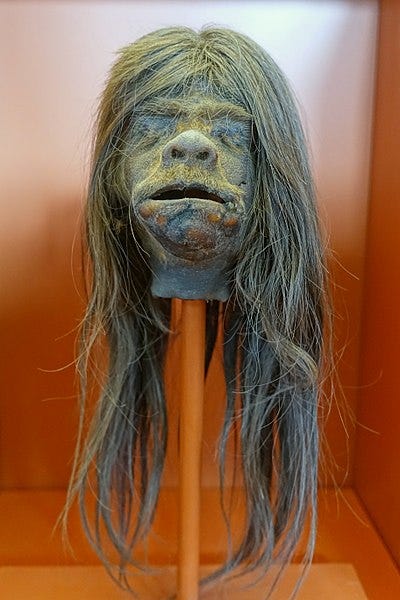

Tsantsa are shrunken heads—often from humans, but sloths were also common—traditionally made by Jivaro people in Peru and Ecuador. They are complicated objects—from the process of producing them, the supernatural beliefs that motivated their creation, the colonial collectors who created economic incentives to manufacture them, and the ‘modern’ perception of them as cultural materials—nothing about their history is simple.

It is important to emphasize that some Tsantsa are human remains, and the treatment of the dead in probably most societies is a particularly sensitive topic. On these grounds alone I think concern and caution about their public display is reasonable. However, the particular reasons given by the Pitt Rivers Museum for their removal, and what they say about the challenges of presenting cultural diversity to unfamiliar audiences, are worth exploring further. In the news release announcing the removal, they write,

audience research showed that, although popular with some, visitors mostly understood the Museum’s displays of human remains as a testament to other cultures being “savage”, “primitive” or “gruesome”, revealing that the displays did not align with the Museum’s core values of enabling our visitors to reach deeper understanding of humanities’ many ways of being, knowing and coping but reiterated racist stereotypes.

If visitors are coming away from these displays with nothing more than the idea that such practices are “savage”, then the museum is correct to consider this a failure on their part, and to seriously reconsider how these materials are displayed. The challenge though is that “humanities’ many ways of being,” includes traditions such as the making of shrunken heads. The task of museums and the job of the anthropologist, it seems to me, is to present traditions that outsiders may be unfamiliar with, or even initially hostile to, in ways they can charitably understand. ‘To make the strange familiar, and the familiar strange,’ as the old adage goes.

The response from museum visitors to these objects is quite revealing. Many people in contemporary industrial societies are much more ‘viscerally insulated’ from recurrent exposure to blood, death, and disease than most people throughout the rest of human history, where infant and child mortality were consistently high, before institutions of medical and mortuary specialists, where people had to directly deal with and dispose of the dead themselves. Butchers, doctors, forensic anthropologists, morticians and the like become habituated to this kind of exposure, while many in the general population have the luxury of remaining much more averse to it.

But really, why should ‘modern’ people be so judgmental of these objects? The preservation and display of animal remains is known as taxidermy to English speakers, and has been a common practice for the last two hundred years or so. As noted previously some Tsantsa consist of animal heads—a young Jivaro man would make his first Tsantsa from a sloth he’d hunt and kill as part of his initiation into manhood.

There are naturally sensitivities involved when it comes to the display of human remains, but it is not as though such practices are entirely foreign to ‘modern’ societies. I vividly remember my mother’s open casket funeral—they had done her face up in far more make-up than she ever wore when she was alive. The professionals at the funeral home obviously had to spend time preparing her body for display, again you’d expect those less habitually exposed to dead bodies and their treatment to be more uncomfortable with practices related to it.

The violence involved in the creation of the tsantsa may naturally be a point of concern for visitors, though it is worth noting also how Western collectors in the 19th and 20th centuries incentivized and exacerbated the practice. Anthropologist James Boster writes that,

it was the exchange of tsantsa for trade goods, especially shotguns and carbines that ultimately vastly increased the intensity of intertribal warfare and added a material basis to the ideological system…The market for trophy heads greatly accelerated the course of Jivaroan head taking: Jivaroans would trade heads for shotguns, and as conflict escalated and shotguns became vital, more heads were converted into trophies. The process continued until roughly half the adult men had shotguns and the other half were headless.

The introduction of shotguns and the creation of an economic incentive greatly expanded the creation of tsantsa beyond their traditional role in feasting and the core ideological motive of the retention of, and protection from, malicious enemy ‘souls’.

As unique and interesting as the tsantsa are, they are just one of many traditions found throughout history involving the preservation and display of human heads, including across historical European societies. Many Classical Greek authors wrote of Celtic headhunting and the use of oils to preserve the heads, which has been supported by modern archaeological findings.

If museums are not managing to display items like these in such a way that unfamiliar visitors may learn more humanizing information about them, without just affirming some simple cultural prejudice, then rethinking how they are displayed is absolutely necessary. Maybe various factors, such as the particular sensitivities around human remains, and the visceral insulation of much of contemporary industrial society, are too much of a barrier for some visitors to develop a less judgmental understanding from a limited museum encounter.

But finding a way to portray and discuss sensitive cultural traditions is one of the most important and valuable parts of anthropology. I started my website Traditions of Conflict four years ago, to focus particularly on these kind of traditions, and what they can tell us about a universal ‘human nature’. The beauty of a magnificently carved Nuxalk house pole is going to be self-evident to many, while it is in the well-documented cross-cultural traditions of violence and inequality where direct discussion by anthropologists to provide context and understanding is most essential.

– William also writes at Traditions of Conflict.