Notes on Progress: Doing science backwards

Preregistering research as a cure for scientific bias

Notes on Progress is a new diary-style format from Works in Progress, where some of our writers give a personal perspective on the work they’re doing and some of the questions they’re grappling with. This is an experiment, so let us know what you think as we send these out over the next few months. If you only want to hear when we have a new issue, you can opt out of Notes in Progress here.

Here, Stuart Ritchie writes about pre-registration in science. If you enjoy this issue, please share it on social media or by forwarding it to anyone else you think might find it interesting.

Science is almost always done backwards.

That’s what I’ve concluded over the past few months, while working on a new kind of scientific publication with my PhD student Anna Fürtjes. The study aims to help neuroscientists choose which of the many “brain atlases”, maps that split up the outer cortex of the brain into lots of regions that might be of particular interest, to use in their research.

The exact details of the study don’t matter, though, because it’s the way we’re publishing it that’s of interest here. Usually, the process of publishing such a study would look like this: you run the study; you write it up as a paper; you submit it to a journal; the journal gets some other scientists to peer-review it; it gets published – or if it doesn’t, you either discard it, or send it off to a different journal and the whole process starts again.

That’s standard operating procedure. But it shouldn’t be. Think about the job of the peer-reviewer: when they start their work, they’re handed a full-fledged paper, reporting on a study and a statistical analysis that happened at some point in the past. It’s all now done and, if not fully dusted, then in a pretty final-looking form.

What can the reviewer do? They can check the analysis makes sense, sure; they can recommend new analyses are done; they can even, in extreme cases, make the original authors go off and collect some entirely new data in a further study – maybe the data the authors originally presented just aren’t convincing or don’t represent a proper test of the hypothesis.

Ronald Fisher described the study-first, review-later process in 1938:

To consult the statistician [or, in our case, peer-reviewer] after an experiment is finished is often merely to ask him to conduct a post mortem examination. He can perhaps say what the experiment died of.

Clearly this isn’t the optimal, most efficient way to do science. Why don’t we review the statistics and design of a study right at the beginning of the process, rather than at the end?

This is where Registered Reports come in. They’re a new (well, new-ish) way of publishing papers where, before you go to the lab, or wherever you’re collecting data, you write down your plan for your study and send it off for peer-review. The reviewers can then give you genuinely constructive criticism – you can literally construct your experiment differently depending on their suggestions. You build consensus—between you, the reviewers, and the journal editor—on the method of the study. And then, once everyone agrees on what a good study of this question would look like, you go off and do it. The key part is that, at this point, the journal agrees to publish your study, regardless of what the results might eventually look like.

This is what happened to us: reviewers had some brilliant suggestions for analyses we hadn’t considered—especially helpful when, as with our brain-atlas project, the idea is to write a paper that’s practically useful to other researchers—and we agreed to run them. Anna has just finished all the statistics, and we’re safe in the knowledge that we’ll definitely get a publication (so long as the reviewers, who get a second look, agree we’ve done what we promised).

That pre-agreement to publish is revolutionary, and not just for switching around the order of study and review. It also deals with publication bias. The editor’s decision to publish isn’t based on how cool, or exciting, or politically-agreeable, the results look – it can’t be, because at the time of the decision those results don’t exist yet. It’s based on how solid the design of the study is. And on the part of the authors, there’s far less incentive to fiddle, p-hack, or hype the results to get a publication: they’d get one either way (moreover, they’d already agreed on all the analyses, so can’t just alter them without the reviewers noticing).

Back in ’38, Fisher argued that you could get a lot more out of your experiment if you brought in the statistician before you ran the study:

A competent overhauling of the process of collection, or of the experimental design, may often increase the yield ten or twelve fold, for the same cost in time and labour.

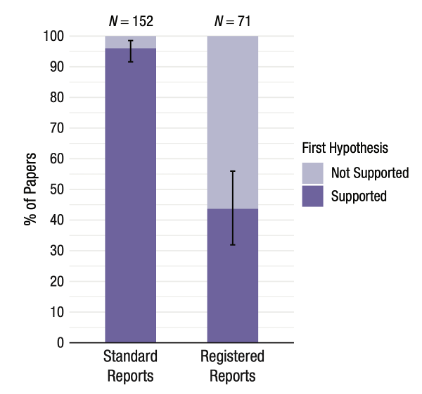

That might well have been true in Fisher’s own area, agronomy. But in a field like psychology, we might expect Registered Reports to give us fewer results – or, more accurately, more null results. That’s because the vast, vast majority of psychology papers that are published the standard way—96%, by one estimate—report positive results. That’s far too many to be a real representation of the science, so something has to be going wrong: a combination, most likely, of publication bias (fewer null results getting published), p-hacking (null results being changed into positive ones through statistical finagling), and—a knottier problem that we’ll have to work harder to solve—the fact that psychologists don’t set themselves up with particularly “risky” or interesting hypotheses to test.

The paper that found that 96% figure—published in 2021 by my friend Anne Scheel—also checked the percentage of positive results in Registered Reports in psychology: it was 44%.

Is 44% a more realistic estimate for how many positive results we should be getting in psychology? Not quite. Certainly, the drop from 96% to 44% in part shows what happens when you’re locked in to publishing regardless of whether the results went the way you wanted, and when you rule out lots of p-hacking and the like. But there’s also a selection bias: people who choose to do a Registered Report are probably going to be the more careful scientists, since they’re interested in new, reform-led ways to improve scientific practice. Registered Reports might also be used more often for attempting to replicate dodgy-looking results, which—surprise, surprise—don’t usually hold up, producing more nulls.

I’ve argued elsewhere that one possible future for science involves giving up on the idea of scientific papers altogether, and replacing them with living documents, constantly-updated notebooks, or other technology that improves on the dead-tree journal format. But if we must continue with papers—and let’s face it, most scientists will want to—almost all of them should be Registered Reports. I can now personally attest to the process being more productively collaborative, less stressful, more rigorous, and more certain than with any of the many “standard” review processes I’ve been through. Not only that, but I harbour absolutely zero resentment towards the peer-reviewers, which is more than I can say for all the times they’ve forced me to go back and run a million unplanned post hoc analyses on a paper I thought I’d already finished.

At a dinner I recently attended with some science publishers, they emphasized that Registered Reports—though now available at over 300 journals—still make up a tiny proportion of publications altogether. This is unfortunate, since the advantages of the format really can’t be overstated. It’s time to shake ourselves out of our inertia: if you’re a scientist, you should have to explain why you can’t run your study as a Registered Report. If you’re not a scientist, but you read the scientific literature, you should be on the lookout for Registered Reports, which represent, on average at least, a more thought-out study that gives more reliable results.

It’s time, in other words, to finally learn Fisher’s 86-year-old lesson: let’s do science forwards.