Artificial flavoring

"Artificial" didn't scare Americans in the 19th century. Why does it scare us now?

I was reporting an article on synthetic biology when I heard a story about artificial ice. We were in the tasting kitchen at Wildtype, a San Francisco startup that grows sushi-grade salmon from stem cells. A sushi chef had prepared several different samples for me to taste—the dishes tasted like salmon sushi, because that’s what they were—and we were discussing why consumers might prefer vat-grown cultivated salmon to the kind that comes with blood and guts.

“This is the cleanest salmon you will ever have in your life,” boasted company co-founder Aryé Elfenbein. Vat-grown salmon contains no mercury, no arsenic, no microplastics, no parasites—nothing but fish cells. The precisely controlled environment of the cell culture ensures that the raw salmon is free of contaminants. Wild or farmed fish intended as sushi, by contrast, must be frozen to kill parasites. Nature isn’t clean.

Wildtype’s salmon is pure because it’s artificial, I suggested. Elfenbein bristled, preferring to emphasize transparency. The company can provide much more labeling information than you usually get on fish, he suggested, citing the amount of omega-3 fatty acids. But when you’re dealing with animals, I responded, every fish is different. To label their contents you’d have to test each individual salmon. Here, you control what’s in the fish. It’s that artifice that makes labeling possible. “So maybe there’s less variability in this process,” Elfenbein acknowledged.

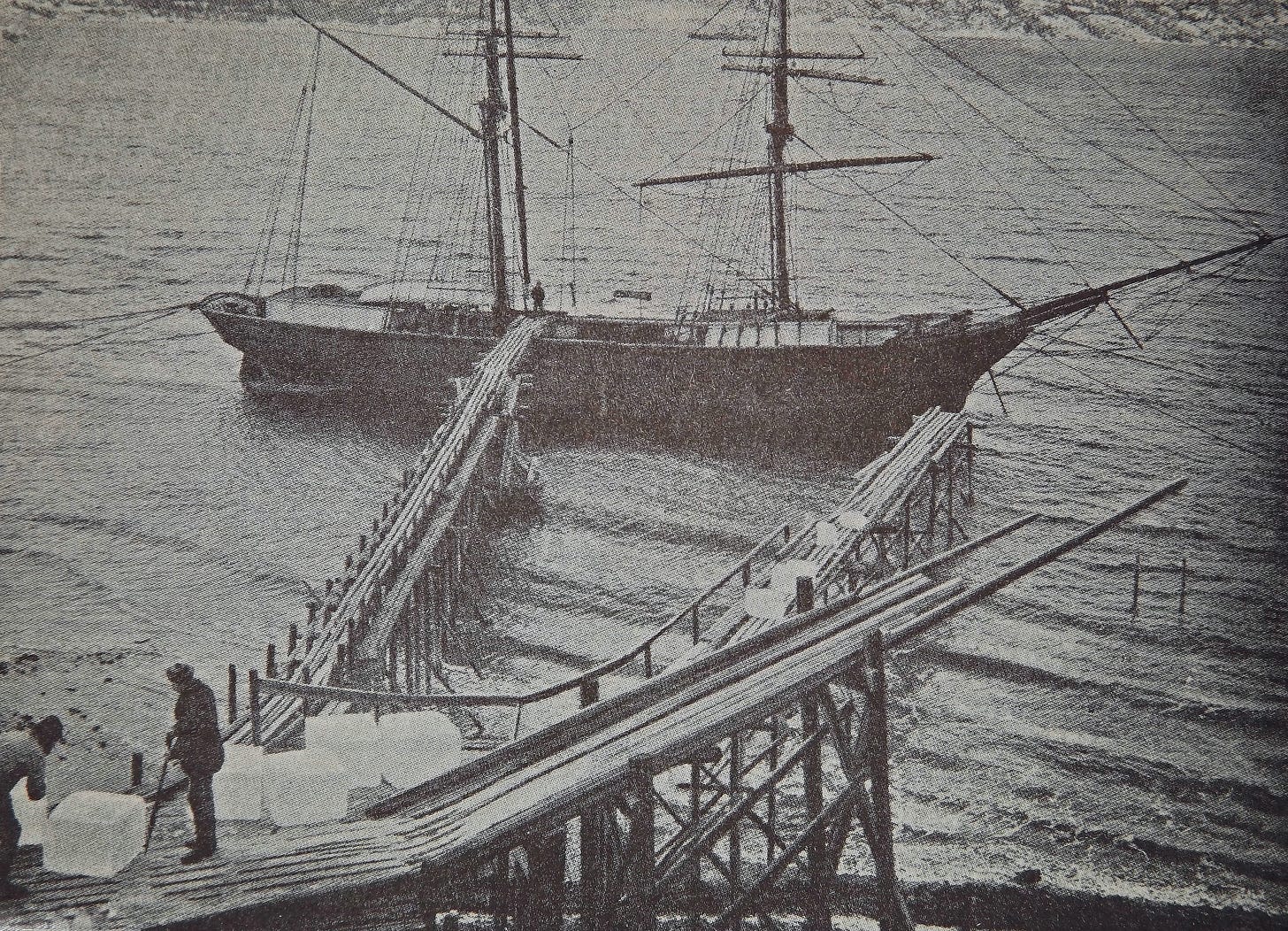

That’s when Dalton Thomas, a sushi chef who works as a food service sales lead for Wildtype, brought up artificial ice. He’d heard the story in How We Got to Now, a TV series based on Steven Johnson’s book by that name. An ice baron who’d made a fortune shipping ice south from lakes and streams in New England found his business threatened when technology was developed to freeze water commercially around 1850. So he sowed fear of “artificial ice,” hurting the new technology’s prospect. I watched the episode on Amazon and, sure enough, Bernard Nagengast from the American Society of Heating, Refrigeration and AC Engineers told the story just as Thomas remembered it.

“They saw a threat to their business by a machine that could actually make the ice,” he said. “And of course, they were the ones who came up with the term ‘artificial ice.’ In other words, fake ice. It’s not real ice.” The ice industry even claimed that artificial ice was likely to carry disease. As Johnson writes, “It was a classic case of a dominant industry disparaging a much more powerful new technology.” Unable to raise money, inventor John Gorrie died broke, without selling any of his refrigeration machines.

But Gorrie wasn’t the only one fooling around with refrigeration in the mid-19th century. “The conceptual building blocks were finally in place, and so the idea of creating artificially cold air was suddenly ‘in the air,’” writes Johnson. Boosted by the Civil War, which cut off ice shipments to the South, the refrigeration business eventually took off, despite the naysayers. That’s the story Johnson tells, anyway.

But it’s too simple. And the claim that public suspicion fed by natural-ice magnates seriously hindered artificial ice is simply wrong. When I went through 19th-century archives at Newspaper.com, I found an entirely positive attitude toward artificial ice. The problem was more mundane than bad publicity. It took decades of technical innovation to get the cost of refrigeration low enough to compete with ice cut from ponds.

In 1865, the Times Union in Brooklyn lamented the (natural) “ice monopoly” that the paper claimed was keeping prices high despite warehouses bulging with unsold inventories. Households were paying wholesale prices of $20 a ton while “market men and butchers” bought at $10 a ton. Artificial ice, although a promising concept, wasn’t yet a viable alternative. “Freezing mixtures are so expensive that no artificial ice has ever been made at a less cost than 5-1/2 cents a pound,” or $110 a ton, the paper reported. But the writer clearly deemed artificial ice a good idea: “Something of this kind, made to work with simplicity and safety, at a small cost, would be a desideratum in many parts of the United States where natural ice cannot easily be obtained.”

Three decades later, the industry was finally taking off. An 1897 article reprinted in many U.S. newspapers began by noting that “it is only within the last ten or fifteen years that the making of artificial ice has become a general industry.” A new process, it reported, was lowering the price so fast that natural ice would soon be too expensive to compete. Far from fretting, the article presented artificial ice as a human triumph: “If these figures are realized nature will be driven from the commercial ice business, and the inventive genius of man will have scored another improvement over his clumsy and antiquated ancestor.”

Natural ice wasn’t deemed authentic or superior. It was “clumsy and antiquated.” Far from an insult, calling ice “artificial” made it more desirable to consumers.

Factory-made ice found a ready market among customers anxious about water-borne diseases and tainted food. Both were serious problems in burgeoning industrial cities. “The demand for artificial ice has been increased by all citizens who are careful to look after the wholesomeness of their food and the general health of their homes,” reported the Fort Wayne News in 1900, noting that “butchers who want no impurities in their ice chests are making a great demand for artificial ice” and “a dutiful mother will have nothing but pure ice for her children.”

In the end, artificial ice triumphed because it was cheaper and more reliable. But the promise of purity and the aura of technological progress gave it an important early allure. To our 19th-century ancestors “nature” was a source of peril rather than purity. That we’re quick to believe they found the label artificial off-putting says more about our culture than about theirs.

Virginia Postrel is a contributing editor to Works in Progress and a visiting fellow at the Smith Institute for Political Economy and Philosophy at Chapman University in Orange, California. Her most recent book is The Fabric of Civilization: How Textiles Made the World.