This is the third issue of ‘Links in Progress’, semi-regular roundups of interesting stuff that's happening in topics that we care about. In this one, Boom’s Phoebe Arslanagić-Little reviews the most important things happening in the world of pronatalism and family policy in the last month. You can opt out of Links in Progress here.

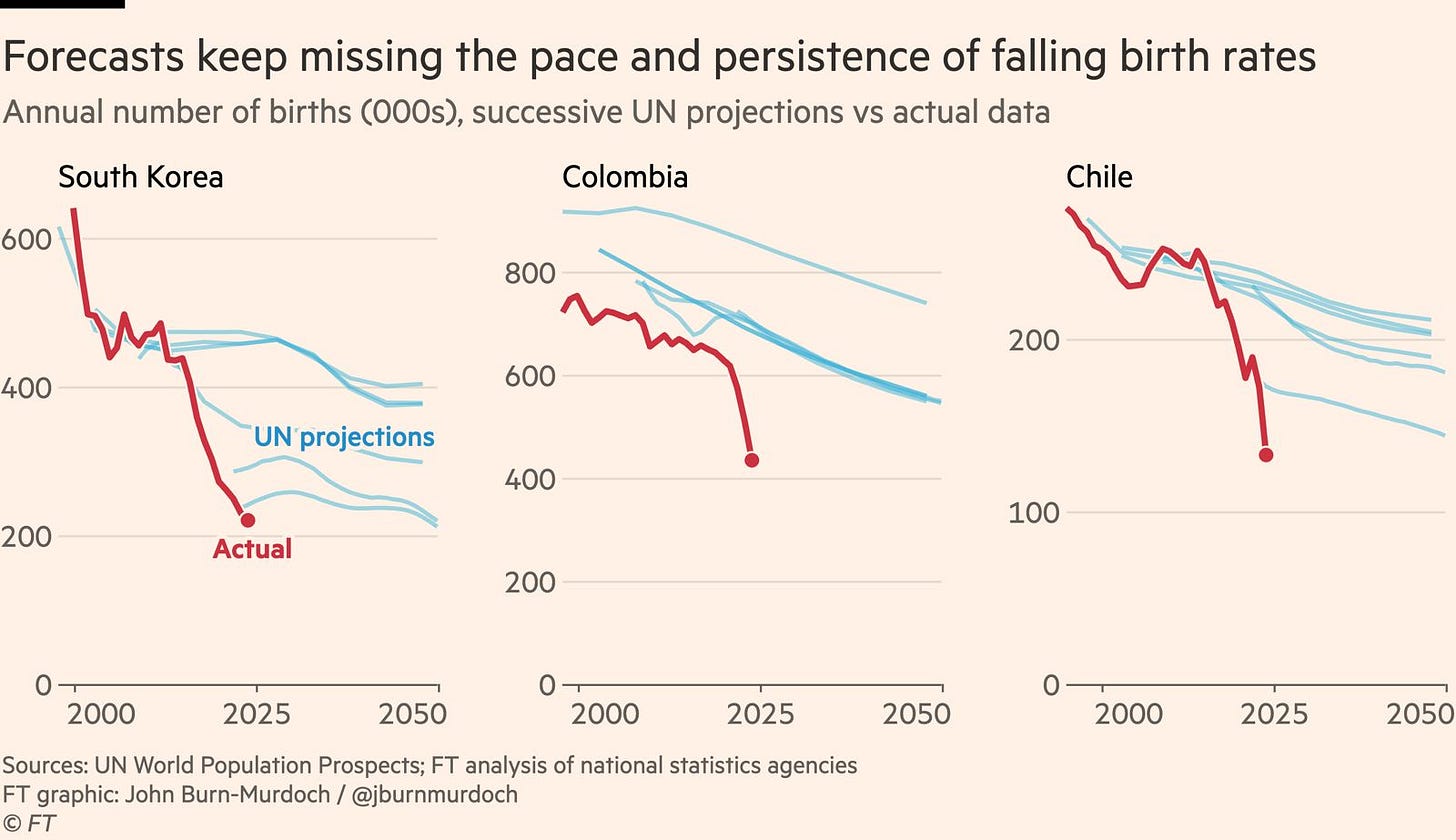

1. The UN’s population predictions and birth rate forecasts keep getting it wrong – there were 30% fewer births in Colombia in 2023 than the UN recently predicted. John Burn-Murdoch explains why peak population might arrive sooner than we think.

2. Ask not what you can do for your baby, but what your baby can do for you. What, exactly, is the point of having children? Philosophers Anastasia Berg and Rachel Wiseman investigate in their new book, What are Children For?: On Ambivalence and Choice.

3. 22% of Americans say not enough babies are being born in the US, but 23% say too many are. YouGov asked the same question of Brits last month and the results are strikingly similar: 20% of Brits say too many children are being born in the UK, and 21% say not enough are. Among Americans, groups more likely to say too many American children are being born include liberals, younger adults, women, and non-parents.

4. In most human societies, poverty does not predict higher fertility, argues US demographer Lyman Stone. He argues the relationship between income and fertility is much more complicated than often claimed, and cultural differences play a big role.

5. In fact, a new study finds that wealthier Dutch people are increasingly more likely to become parents than those on lower incomes. Author Daniël van Wijk also published work earlier this year identifying an intensifying relationship between income level and chance of becoming a parent across multiple countries, including the US.

6. Philosopher Victor Kumar makes the case for progressive pronatalism in the NYT – he argues that if you care about the poor, the sick, and the old, then you should care about falling birth rates too.

7. On the Japanese island of Tokunoshima, fertility has been above the national average for years. Tokunoshima is home to Japan’s two highest fertility municipalities, with respective Total Fertility Rates of 2.25 and 2.24, in comparison with 1.2 for Japan overall. 45% of women aged 20-24 are married in Tokunoshima, in comparison with 7% nationally, and that getting married after falling pregnant is normal and not stigmatized – that could be an important part of the story behind the island’s higher fertility.

8. Taxing the stork? This paper argues that low-fertility countries are not doing enough to take into account and alleviate the costs of raising children upon parents. Even in Nordic nations where parents receive more state support than in other countries, that support does not fully reflect the costs parents face, and parents in these countries (most of whom work) have bigger tax bills. There’s a shorter write-up by study co-author Pieter Vanhuysse here.

9. Low fertility is bad for economic growth, says economist Jesús Fernández-Villaverde in an interview with social scientist Alice Evans. Watch on Youtube or listen on Spotify. Evans has also written about different explanations for the global decline in fertility and the need for a response to this challenge.

10. Economist Emily Oster, made famous by her data-driven approach to pregnancy, has a parenting podcast with The Free Press. The latest episode features Ross Douthat and Bryan Caplan making the case for having children and the fun of being a parent.

11. Ultra-low fertility South Korea has awarded civilian service medals to two mothers for each having 13 children. 59-year old Mrs Lee used her moment in the sun to tell journalists that South Korea “desperately needs” a more parent-friendly workplace culture.

12. A record high of 4.7% of South Korean babies were born outside marriage in 2023, in comparison with only 2.1% in 2013. For comparison: just under 40% of US babies are born outside marriage, 51% of babies in England and Wales, and 65% of French babies.

13. Research in the US suggests that home working may have a particularly positive effect on some groups of women. Specifically, women who are doing well financially, and older women who already have children.

14. 40 years after Christ’s death, there were perhaps 1000 Christians, but by 400 AD there were 40 million of them. Scott Alexander reviews The Rise of Christianity, which investigates what factors may have driven the Christian triumph, including the theory that higher fertility was a major contributor.

15. Different strokes for different folks. A paper looking at family policies in the UK, Germany, and Finland – including more generous paternity leave – shows how and whether such policies affect childbearing varies significantly by women’s education level, and also between countries.

16. While Scotland is seeing a rise in one-child families, the two-child family model remains the norm in England and Wales.

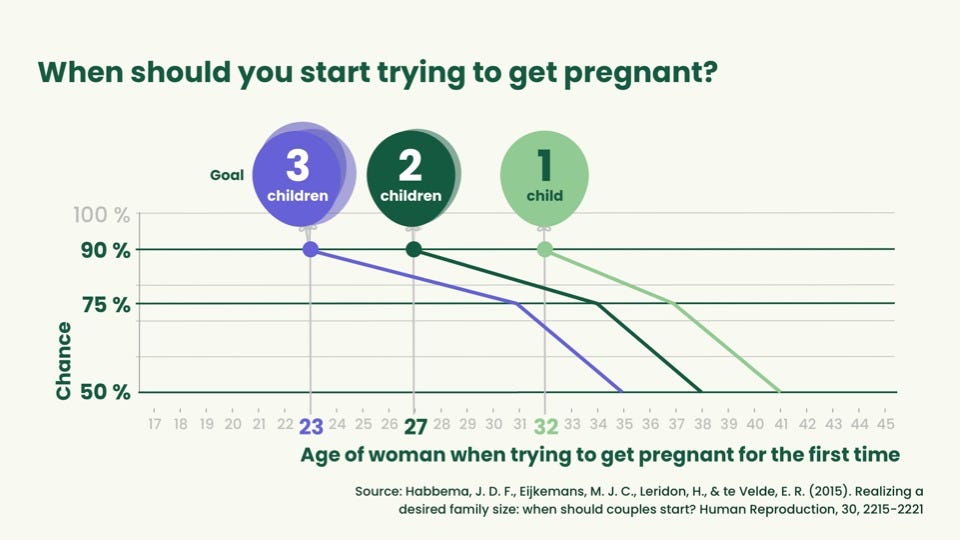

17. How many children would you like? This paper found that to have a 90% chance of having 3 children without IVF, a woman should start trying for her first child aged 23. And for a 90% chance of having 2 children, she should begin at age 27. Demographer Anna Rotkirch has created the below visualization of the paper’s conclusions.

18. Forward-looking thoughts. Finally, I recently read George Eliot’s 1861 novel Silas Marner, about the transformative effect of an adopted child on the life of a recluse whose only comfort has hitherto been money:

“Unlike the gold which needed nothing, and must be worshiped in close-locked solitude… Eppie was a creature of endless claims and ever-growing desires, seeking and loving sunshine, and living sounds, and living movements… The gold had kept his thoughts in an ever-repeated circle, leading to nothing beyond itself; but Eppie was an object compacted of changes and hopes that forced his thoughts onward…”