How writing about nineteenth-century cities changed my mind

More pro-planning, less fussed about privatisation, more pro-monopolies

I recently published a long piece on urban government in the nineteenth century. I have always been interested in nineteenth-century architecture and urbanism, but I wanted to get into the details. I knew the Victorians built gigantic cities very quickly, and that the resulting urbanism was usually a lot better than what we have managed since 1945. But I wanted to study the institutional mechanics behind this. How were the streets planned? Who paid for the pumping stations? Who operated the trams?

Doing so has affected my opinions quite a lot. Here are a few examples:

1. It made me more pro-planning

Living in 2020s Britain, it is easy to become sceptical about planning. Our planning system enormously constricts housing supply, impoverishing the country. The housing and industrial buildings that do get built are often distributed around the country according to political imperatives rather than economic logic. It is natural to think that some sort of Hayekian emergent order would be preferable.

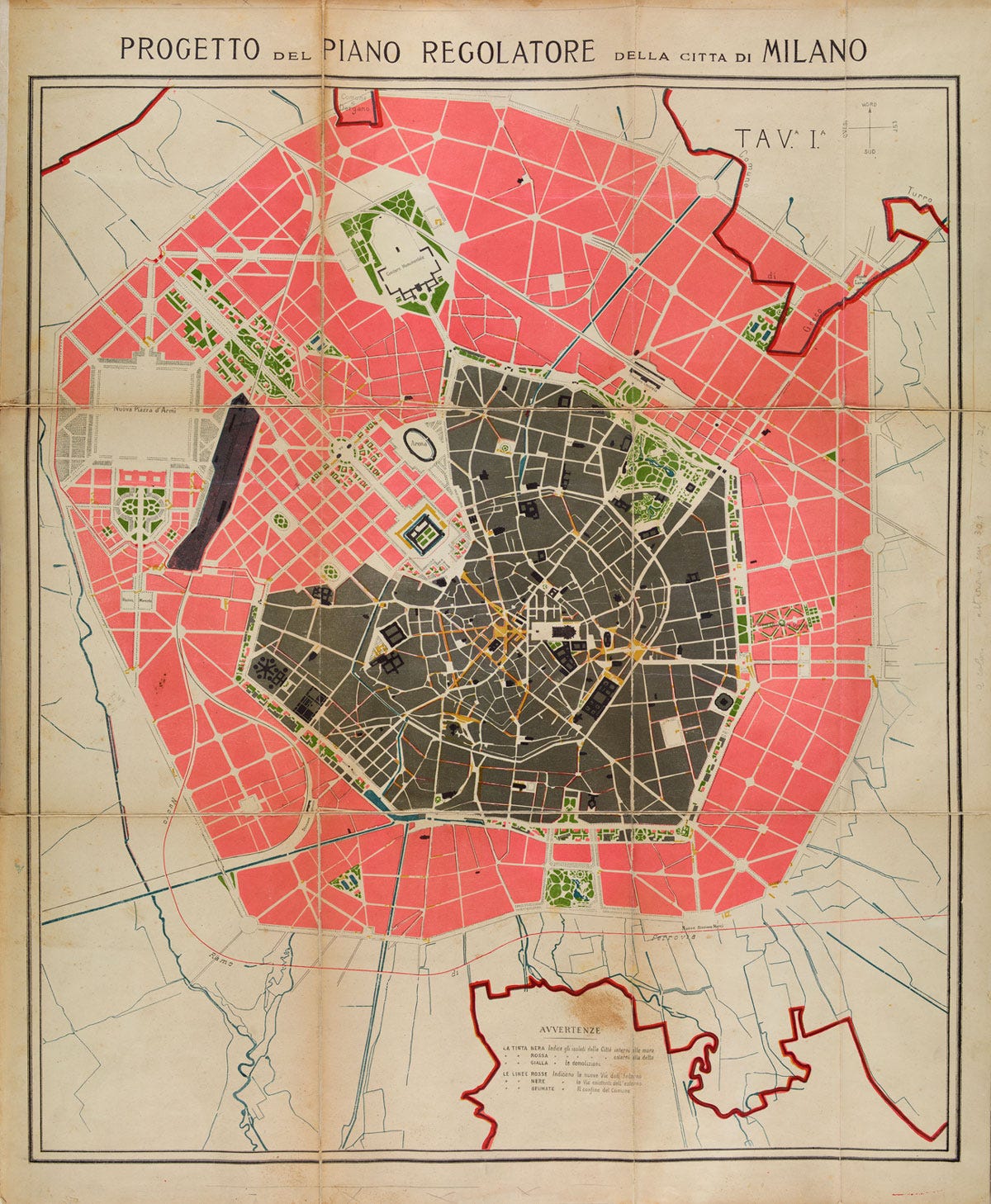

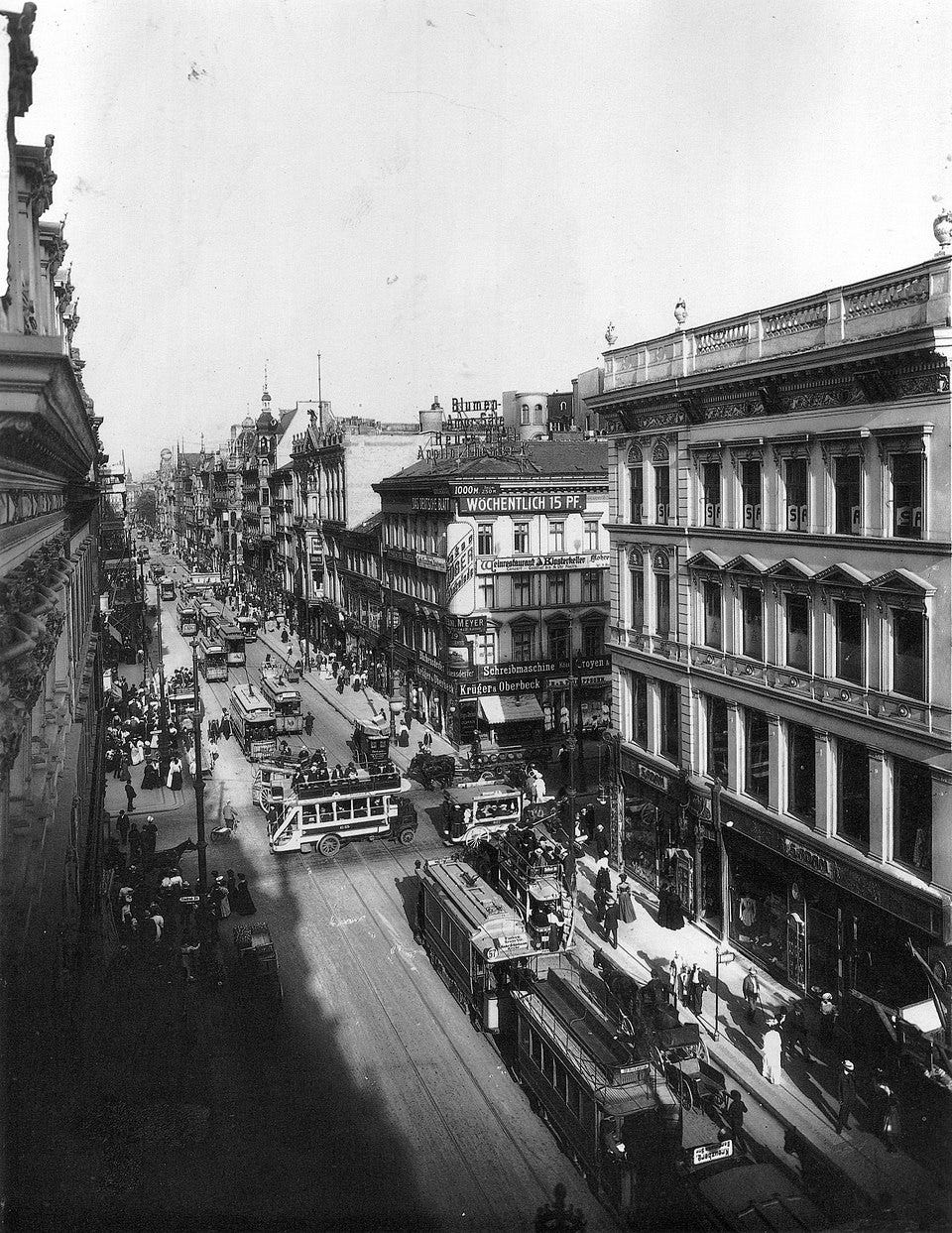

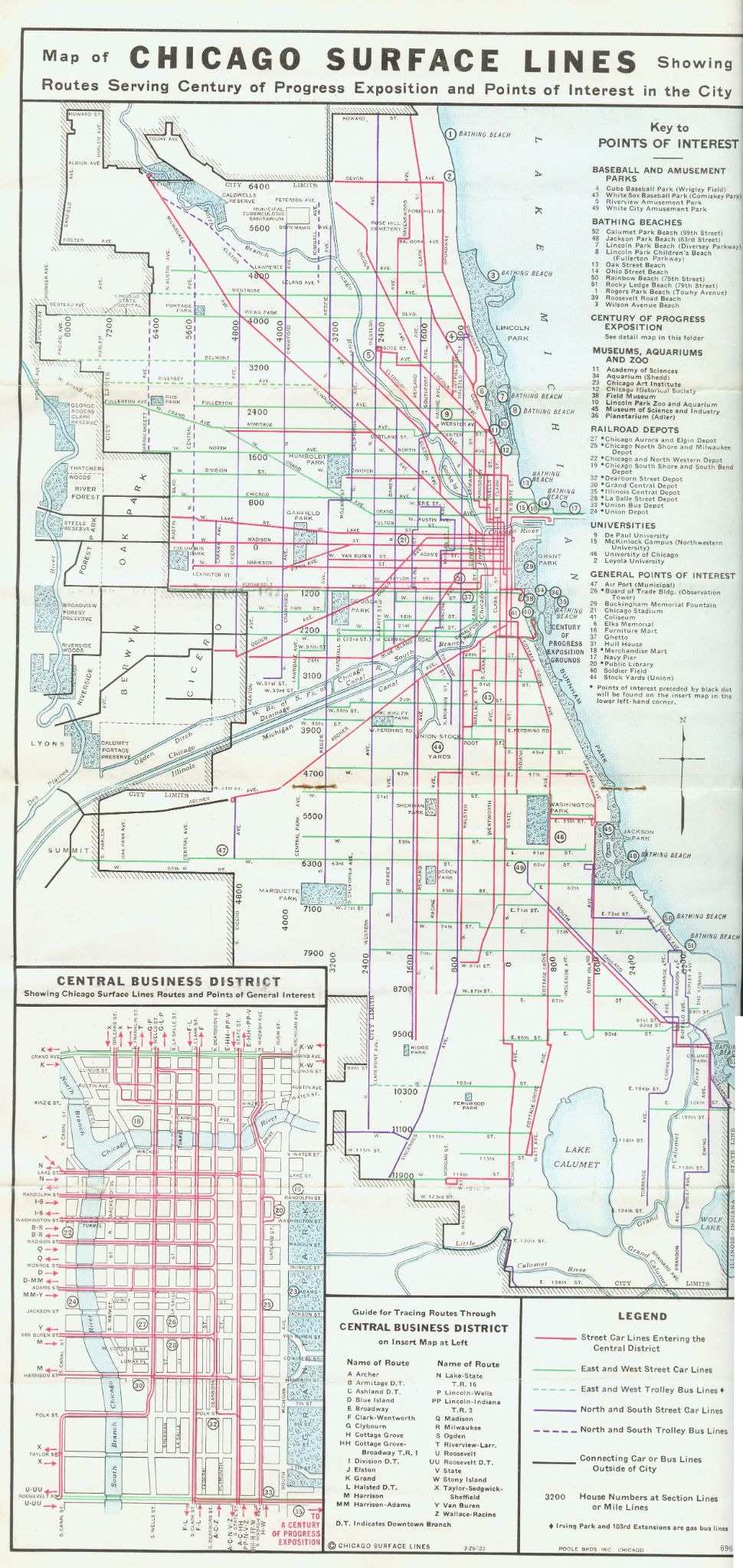

In the nineteenth century, however, we see planning performing its true function, solving the collective action problems inherent in urban life. Planned street networks turn out to be straightforwardly better than unplanned ones: the most planned street networks of the nineteenth century are some of the most successful systems in the history of the world. Urban transit systems also manifestly work better when they are planned by a single authority, and most nineteenth-century governments unified transit ownership accordingly (of which more below).

There is also the interesting fact that most nineteenth-century people voluntarily paid premiums to live in ‘covenanted’ neighbourhoods, which had forms of private-sector development control. This shows that they valued protection from disruptive development by their neighbours more than they valued the development rights foregone thereby.

Covenanting wasn’t very effective, but its prevalence reveals that there was genuine and broad demand for development control before the state started providing it. That doesn’t necessarily mean that such development control was morally good – maximising economic value need not realise the morally best outcome. Nor does it mean that the degree of development control we have today is value-maximising, even in the narrow economic sense. But it does mean that some level of development control has genuine popular support, and is not an extraneous state imposition.

2. It made me care less about public or private ownership

I was aware that a lot of nineteenth-century infrastructure was built by private companies, and also that the Victorians were great infrastructure builders. In Britain, Parliament famously granted compulsory purchase powers for 9,500 miles of railways in 1846, 67 times longer than the catastrophic HS2 railway it is trying to build today. In America, most cities had superb public transport in the nineteenth century, actually much better than they do now. This suggested to me that private ownership worked a lot better than public ownership has.

Closer inspection reveals that the public/private distinction was not as important as I thought. Some nineteenth-century infrastructure was owned by private companies, but other infrastructure was owned by municipalities. Intracity transport and utilities in Germany were normally owned by municipal companies called Stadtwerke, and by the early twentieth century this was increasingly true in England too; in France they were also owned by the state, though operated by private concessionaires. There is no clear evidence that these systems were worse than the private franchises that predominated in the USA, and indeed the German Stadtwerke were often seen as world-leading.

The real differences seem to be elsewhere. Nineteenth-century urban infrastructure was funded almost entirely by user fees, not subsidies. It was far less price-controlled than modern infrastructure, so it was generally profitable to supply, and suppliers raced to meet rising demand. If they were particularly incompetent, they went bankrupt. This was true even if they were municipalities: if a city went bankrupt in the nineteenth-century, that was its problem, not the national government’s. These features generated a set of benign incentives that were surprisingly similar across both the public and private sectors, leading both to operate infrastructure fairly efficiently.

3. It made me more interested in monopolies

We are all familiar with the idea that monopolies are bad, and no doubt they have some serious disadvantages. Because monopolies are not under competitive pressure, their incentives to be efficient are weaker, and because they almost never go bankrupt, they are not subject to selection effects. They may also have opportunities to exploit their market position to charge higher prices than is socially optimal.

Interestingly, however, the hugely successful urban infrastructure of the nineteenth century was nearly all operated by monopolies. A given city would usually have a single company operating its trams, another one operating its gas, another its water, and so on. Governments encouraged and sometimes explicitly required this. One justification for this was that infrastructure has so many positive spillover effects that monopolistic pricing was in fact efficient in this case: you want infrastructure to be more profitable to supply than it is in a competitive market, because it is just so good to have more of it. Another justification was that it led to a better coordinated network, rather than the chaotic duplication that occurred in competitive markets.

Some countries even found ways of partly replicating the pro-efficiency incentives and selection effects of competitive pressure. Under the French concession system, virtually all urban infrastructure was owned by the municipalities but operated by private companies. Municipalities awarded time-limited concessions to whichever company offered the best deal. This clever system, which still exists today, got many of the advantages of competition while preserving the advantages of infrastructure monopolization.

Samuel Hughes is an editor at Works in Progress. Follow him on Twitter.

Is it fair to say that a general theme here is to care less about ideological versions about what works vs doesn’t, and just focusing on planning and executing infrastructure buildout with whatever tools you can?

Thanks for the summary Sam, good insights as ever. There is one point though that would deserve a better justification IMO: "you want infrastructure to be more profitable to supply than it is in a competitive market, because it is just so good to have more of it".

How good is it really to have more infra, especially roads, railways and public transport? Are there any (at least somehow rigorous and data-driven) approaches to quantify the benefits, especially the spillover effects? I have been thinking about this for some time but still have no clue, beside a CBA working with saved travel time and distance and some rather handwavy environmental criteria.