We’re experimenting with turning on comments on our Substack. We're excited to see what you say about our pieces!

Michael Hopkins writes about progress on the high seas for Issue 17. Read it on our website here.

In January 2024 the largest passenger ship ever built, Icon of the Seas, set sail from Miami on her maiden voyage. Icon is five times larger than the Titanic by gross tonnage (the internal volume of a ship) and spans 20 decks containing more than 2,500 passenger rooms. At full capacity she can carry nearly 10,000 people – up to 7,600 passengers along with 2,350 crew. Passengers can enjoy 40 bars and restaurants across eight ‘neighborhoods’, plus several theaters and a top-deck aquapark comprising seven swimming pools and nine waterslides. The ship is 365 meters long and 65 meters wide, giving a population density equivalent to approximately 420,000 people per square kilometer. That’s about 70 times the density of London and 50 percent higher than Dharavi in Mumbai, often cited as the world’s densest urban area.

Airplanes today fly no faster than they did in the 1970s. In many countries, road speeds have decreased. Flying cars never showed up. In developed countries, the tallest buildings have only inched higher. Most rich countries produce less energy per capita than they did 20 years ago, and the cost of building new physical infrastructure like railways seems to rise inexorably. Yet cruise ships continue to grow: a natural experiment in what can be achieved outside the constraints that have stifled progress on dry land.

A brief history of very large ships

Between the latter half of the nineteenth century and the jumbo jet’s maiden commercial flight in 1969, people mostly traveled between continents on ocean liners, the largest passenger ships of the era. Though often luxurious, ocean liners were primarily a mode of transport. The most important consideration was speed.

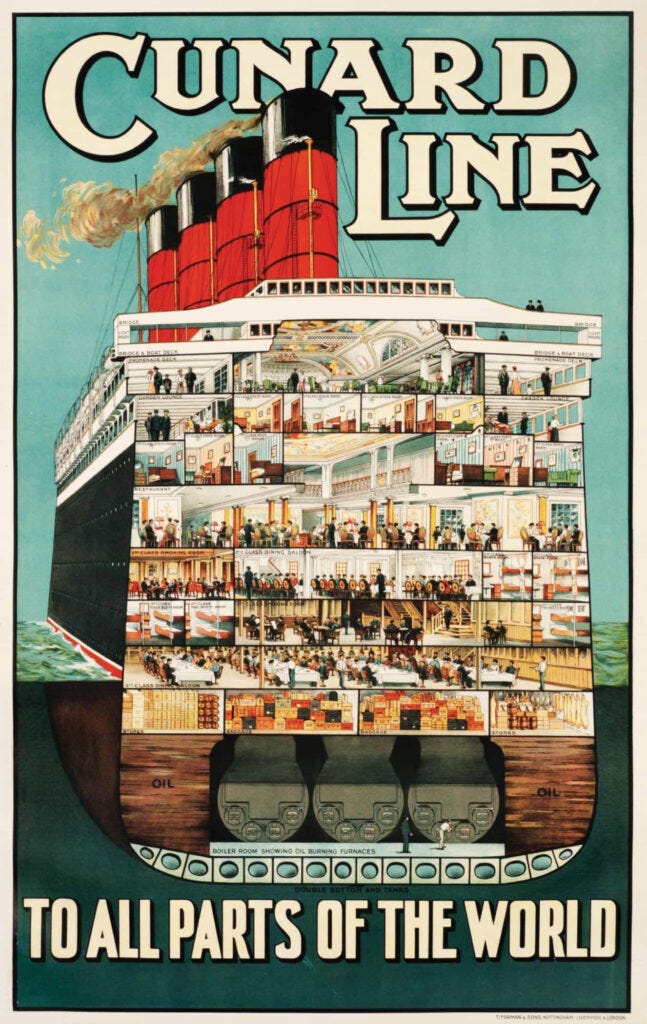

The Titanic’s sinking in 1912 did not kill the ocean liner. In the 1910s and ’20s the Cunard Line ship RMS Mauretania could cruise at 25 knots (46 kilometers per hour) and held the Blue Riband, an unofficial award for the fastest Atlantic crossing by a ship doing a regular trip, with a crossing time of just under five days. Companies competed on speed and in the 1930s newer, faster ocean liners like the SS Normandie and RMS Queen Mary were introduced with a cruising speed of 30 knots, reducing the transatlantic crossing time to around four days.

The invention of the modern passenger jet in the late 1950s cut transatlantic journeys from days to just hours. When jet travel became cheaper in the late 1960s the ocean liner companies were left in a difficult position. Reduced demand for transatlantic crossings on their huge, expensive ships necessitated a pivot to a new offering: voyages in warmer waters calling at tourist destinations on ships packed with amenities. The leisure cruise was born.

The history of the SS France illustrates this transition. Launched in 1960 by Compagnie générale transatlantique, or French Line, as the world’s longest passenger ship (at 316 meters long), she became the flagship transatlantic liner of a dying industry. Airline competition and the oil crisis of the early 1970s forced her into early retirement in 1974 and she lay dormant for five years before being bought by Norwegian Cruise Lines in 1979. Norwegian renamed her the SS Norway, and she became their largest Caribbean cruise liner. Her heavy, oil-powered steam engines were converted to diesel and the old passenger rooms and public areas were redesigned to suit tropical cruises, adding luxurious suites and onboard amenities like new bars and lounges, a casino, and a discotheque. The SS Norway served as a cruise liner for 30 more years before being decommissioned in 2003.

You can read the rest of the piece here.

Michael Hopkins is a writer.

I just want to comment to say please keep posting these articles on Substack. I would like to find time to read WIP much more often, but it slips my mind. If it’s right there in the Substack app I can get it where I go to read articles anyway. Thanks.

The illustration of the massive progress in cruise ships indeed evokes a sense of unbounded optimism. This trend is also evident in the evolution of modern cargo ships, which have grown significantly in size and capacity.

However, all good times may come to an end. The International Maritime Organization (IMO) has recently announced ambitious and, in my view, unrealistic decarbonization targets. The entire shipping industry is required to cut emissions by 30% by 2030, 70% by 2040, and achieve net-zero by 2050. Non-compliance with these targets will result in substantial penalties: a $100 per tonne CO2 tax for slight non-compliance and a $380 per tonne tax for significant non-compliance.

These targets seem overly stringent and impractical. I had not anticipated such aggressive measures from the IMO, which has historically maintained a relatively laissez-faire approach. For context, the EU economy is already struggling with a carbon price of $60-70 per tonne. The IMO's new regulations could either force a reconsideration of these targets or risk disrupting the global trading order.