From the vault: How pour-over coffee got good

While popular with enthusiasts, pour-over coffee frustrated shops because it takes so long to make, but that's changing.

Nick Whitaker writes about developments in making coffee, for Issue 16.

In the US, almost every coffee shop serves drip coffee. It’s made from a machine similar to the ones many Americans have at home. You put a filter paper full of coffee grounds in, the machine dispenses hot water over it, and a pot is filled with coffee.

There are many ways of brewing coffee, though. One is especially elegant, technical, and ritualistic: the hand-brewed pour-over. In the last 20 years, pour-over has become a symbol of quality and craft in coffee.

Pour-over is a challenge for coffee shops. Many are proud to offer it, but the time-consuming process interrupts service and often produces inconsistent results. How to brew the perfect cup of coffee remains a vexing question. Like espresso, new technologies might be poised to revolutionize coffee brewing at home and in the café.

When you think of pour-over coffee, you might think of the V60, the iconic dripper from the Japanese company Hario. Today it’s probably the most popular dripper. But the V60 is a recent development, launching in 2005. The motivations behind the brewer begin much earlier.

Coffee – and what Americans like me mean by that is black coffee, filter coffee, drip coffee – is much more popular in the US than Europe. It became popular after the Boston Tea Party as a more patriotic alternative to the unjustly taxed tea. While the modern espresso machine debuted at the 1906 World’s Fair in Milan, a machine didn’t come to the New World until 1927, when Caffe Reggio in Greenwich Village acquired one. The machines weren’t readily taken up outside Italian American communities until after the war, first by beatniks and artists in espresso cafés in San Francisco and New York. Espresso didn’t explode until Peet’s Coffee – and the more popular shop it inspired, Starbucks – spread across the country beginning in the 1970s. Still, it remains less popular with Americans than a standard cup of coffee.

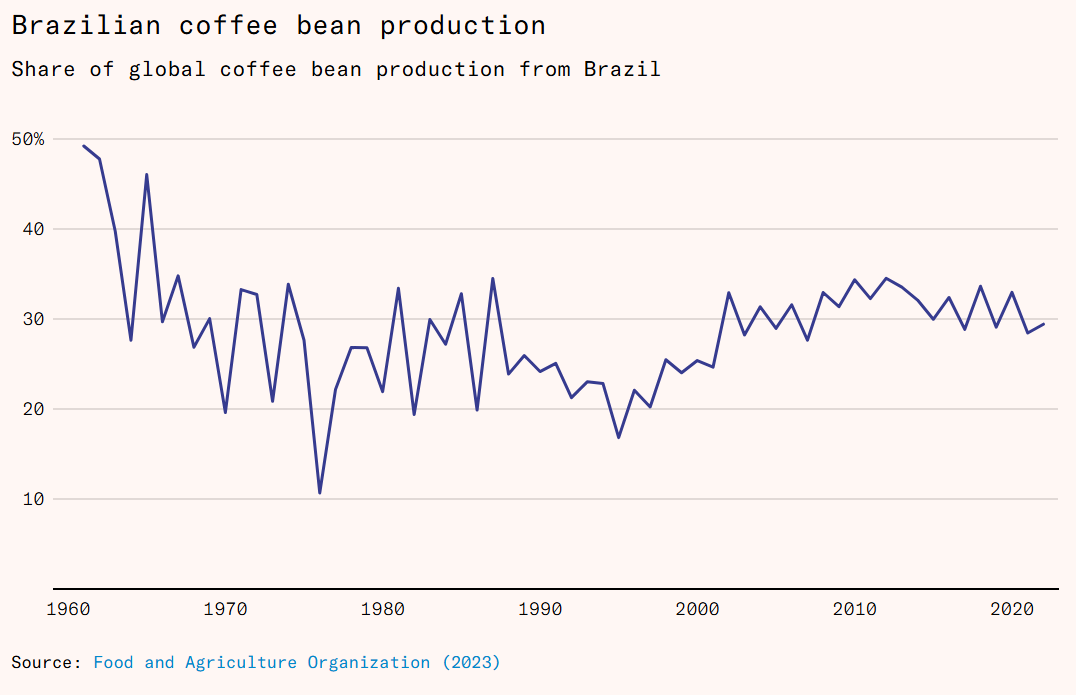

Pour-over, coffee brewed by hand with a gooseneck kettle and dripper instead of a machine, has similar origins to modern espresso: starting in the 1970s, coffee began to slowly escape its status as a commodity product, where all beans were treated as one. Peet’s began to emphasize their coffee’s country of origin. Brazil has long been a monster coffee producer – today it still accounts for around 30 percent of global coffee production. But consumers began to branch out to coffee from places like Sumatra, Indonesia, or Sidama, Ethiopia.

As modern, specialty coffee really got going in the early 2000s, shops like Intelligentsia in Chicago and Stumptown in Portland placed an even greater focus on the origin of the coffees they served, roasting lighter and naming specific farms or cooperatives alongside the country of origin. Lighter roasts emphasize brighter flavors – the lists of fruit or flowerlike notes that can now be found even in grocery stores – but these coffees also have a tart acidity and run the risk of the grassy, not-quite-coffee taste that comes from too light, ‘underdeveloped’ roasts. Avoiding these flavors and roasting lightly well is difficult and involves a number of advanced techniques, like a ‘declining rate of temperature rise’ throughout the roasting process (a negative second derivative – coffee gets surprisingly technical). In the late 2000s, software like Cropster let roasters track their data and iterate, making it much easier.

A new world of coffee was created: specialty coffee consumers did not simply want super-dark French roast coffees that always tasted like caramelization, chocolate, and smoke, no matter the origin. They wanted a buffet of coffee offerings from around the world.

This put coffee shops in an awkward position. Few coffee shops had the volume to offer more than two or three coffees as batch brews, made in industrial-sized coffee machines. Brew too much coffee and it would become stale or tepid before it was finished. In practice, this often amounted to three vats of coffee behind the bar: a dark roast, a light – though not usually very light – roast, and a decaf.

Coffee shops wanted to sell many different types of beans for customers to take home. As desire for single-origin coffees spread, shops would sell 10 or even 20 different coffees. With only two or three brewed coffees for sale, café goers wouldn’t be able to sample most of the offerings. And – despite the European allure of the espresso shot – a well-brewed cup of coffee is often the best way to appreciate complex, fruit-driven coffees that the coffee world was increasingly excited about. Espresso is so concentrated that it is hard to decipher the different notes and flavors. It’s a bit like why people sometimes add water to whiskey. This is why the very best coffee shops in England and Europe serve drip coffee, despite most of the Continent preferring espresso.

In response, some shops began offering pour-over. This was the founding promise of Blue Bottle Coffee, the famous San Francisco shop, when they started in 2002: ‘to brew coffee to order, using the pour-over method’. Even after being purchased by Nestlé and growing to over 100 shops, Blue Bottle’s black coffee is still hand brewed.

Many shops are less willing to do this and the reason is simple: time. A pour-over in ideal conditions takes about three minutes to brew, not to mention another minute or two for prep and clean up. A skilled barista could make ten espresso drinks in that time. A nice café near my office has a warning on the menu: ‘manual brew, wait time 10 minutes’. That shouldn’t be too surprising – recall that espresso was invented as a time-saving measure. Nevertheless, consumers would almost never be willing to pay commensurate with this time cost – variety wasn’t worth ten-dollar cups of coffee.

You can read the rest of the piece here.