Heat waves

Why a hotter world might be a more dangerous, violent, and less productive one

Notes on Progress are pieces that are a bit too short to run on Works in Progress. In this piece, Deena Mousa investigates the human costs of a hotter world.

The window of safe internal temperature for the human body is remarkably narrow: 36.1°C to 37.2°C. Outside it sits hypothermia on one end, heatstroke on the other. As the body’s internal temperature changes, it begins to thermoregulate to stay within that window. To handle overheating, blood vessels near the skin dilate to increase heat loss, the heart beats faster and harder, more than doubling its output to support this, and sweat cools the body through evaporation.

Singapore’s founding father Lee Kuan Yew said that his first act as prime minister was to install air conditioners in buildings where the civil service worked. Air conditioning, Lee argued, ‘made development possible in the tropics’ – cooler indoor temperatures kept workers productive in the midday heat. Temperature extremes, he recognised, weigh down on people’s health, mood, cognition, and productivity.

This summer, a heat wave struck Mexico and temperatures soared above 45°C in much of the country. Heat-related illnesses overwhelmed some hospitals, and the surge in electricity demand for air conditioning led to rolling blackouts. In Saudi Arabia, more than a thousand pilgrims died as temperatures hit 50° C. There have been six heat-related deaths of hikers in Greece since the start of the tourist season, including British doctor and television presenter Michael Mosley. This summer’s heat is not yet over, so it is difficult to approximate its burden, but researchers estimate over 60,000 people died due to the heat in Europe in the summer of 2022.

These are not isolated incidents: there are something like 500,000 heat-related deaths annually. Without a substantial shift in how people and governments approach extreme heat, that toll will only increase as the planet gets hotter.

Heat and human health

The first sign that the body is getting too hot is heat cramps: heavy sweating and painful muscle spasms. Next is heat exhaustion, which involves a fast and weak pulse, nausea, headaches, or fainting. Last comes heat stroke, which can be life threatening.

Those who recover aren’t necessarily in the clear. Exposure to heat injury is also associated with much higher long term risk of heart disease, cerebral stroke, immunosuppression, and chronic kidney disease.

High temperatures also impact mood and mental health; heat makes people more irritable. Emergency-room visits for mental health conditions are eight percent higher in the United States on extremely hot days.

Heat also spurs aggression. When temperatures are high, drivers honk their car horns more often and for longer, and people are more likely to post hate speech. In correctional facilities, one study found that high temperatures increased daily violent interactions by 20 percent. Hotter weather is associated with violent crime, including murder, aggravated assault, rape, terrorist attacks, and mass shootings, though this may be not only because heat relates to stress and aggression, but also because people spend more time outside and in public spaces in warmer weather.

As the climate warms, we may be living in a fundamentally less stable world. Rising temperatures could erode social cohesion at a time when cooperation is most needed, and institutions that are critical for helping us coordinate in the face of these challenges may be more likely to crumble in the heat.

Cognition in high temperatures

The brain represents two percent of body weight, but consumes around a fifth of the body's energy. This high metabolic rate makes it particularly susceptible to heat stress. Higher temperatures can worsen decision-making, reaction time, the ability to sustain attention, and working memory – which are critical for learning, productivity, and safety.

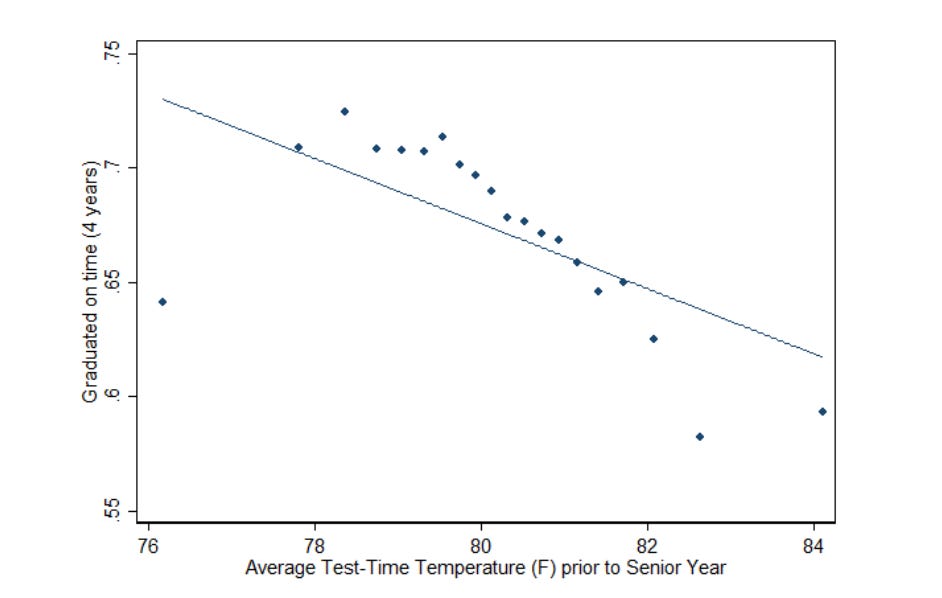

One study found that judges dismiss fewer cases, issue longer prison sentences, and levy higher fines when ruling on hotter-than-average days. In New York City, research found that taking an exam on a 90° F versus a 72° F day was associated with worse exam performance, a 10.9 percent lower likelihood of passing a subject, and a 2.5 percent lower likelihood of graduating on time. Similar results have been found in research in Ethiopia, China, and Vietnam, the PSAT, and the Peabody math test – though other studies in Brazil and Australia found no relationship.

Higher temperatures not only influence cognition in the moment, they can also cause permanent damage – for example, between 10 and 28 percent of heat stroke survivors experience persistent brain damage. These cognitive impacts shape everything from educational attainment and job performance to a society's capacity for innovation and problem-solving.

A growing, uneven burden

Add that up and the economic costs are staggering. Already, some estimates of the economic losses from extreme heat put it at 1.5 percent of GDP in the wealthiest regions and 6.7 percent in the poorest. That translates into a lower standard of living for everyone, not just those directly feeling the heat.

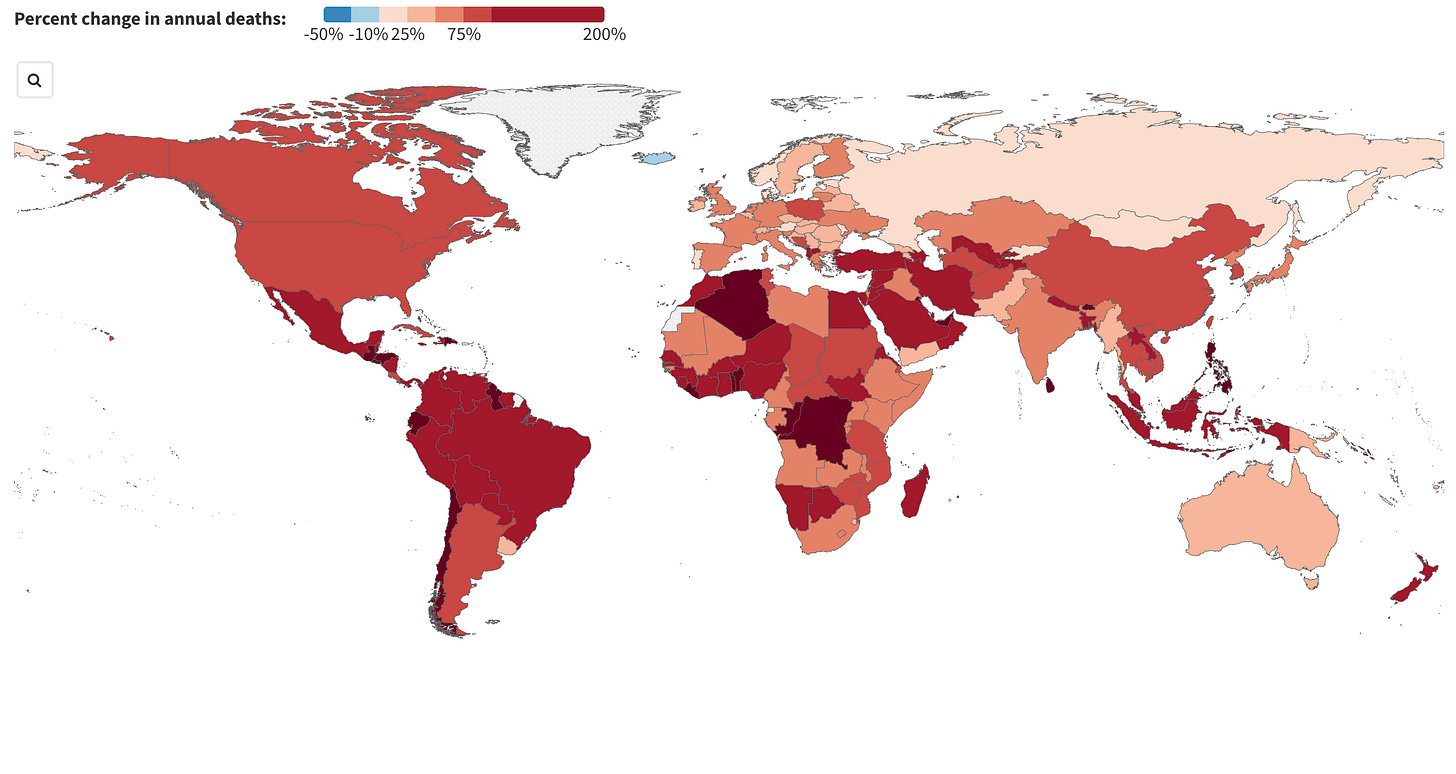

The harms of extreme heat are growing. By 2100, nearly three quarters of the population may be exposed to dangerous environmental heat for at least 20 days each year, up from 30 percent. Heat-related mortality for people over 65 increased by 85 percent between 2000–2004 and 2017–2021. Countries in the global south were hardest hit - leading to worsening global inequalities.

The situation is worsening, but it is not insoluble. We can take adaptive measures while reducing emissions and capturing carbon from the atmosphere, to eventually reverse the changes in climate that are exacerbating these challenges.

One of them is moving heat out of the places where humans are to places where they are not, for example with two-way heat pumps – air conditioners – like Singapore did. Unlike Singapore in the mid-twentieth century, we can now do it without contributing to global warming, as solar panels tend to produce the most energy precisely when it is hottest and air conditioners are most needed.

We can also adjust architectural plans to take into account warming temperatures. Areas that are used to extreme heat are well practiced in doing this: with design elements that can support more cross-ventilation and shading, and more reflective material for roofing that can reduce the heat naturally absorbed by buildings.

Humans have repeatedly transformed hostile environments into livable ones. The growing threat of extreme heat will similarly require urgent adaptation to help us ensure we live healthier and more productive lives around the world.

Deena Mousa is chief of staff for global health and wellbeing at OpenPhilanthropy.