From the vault: Compensating compassion

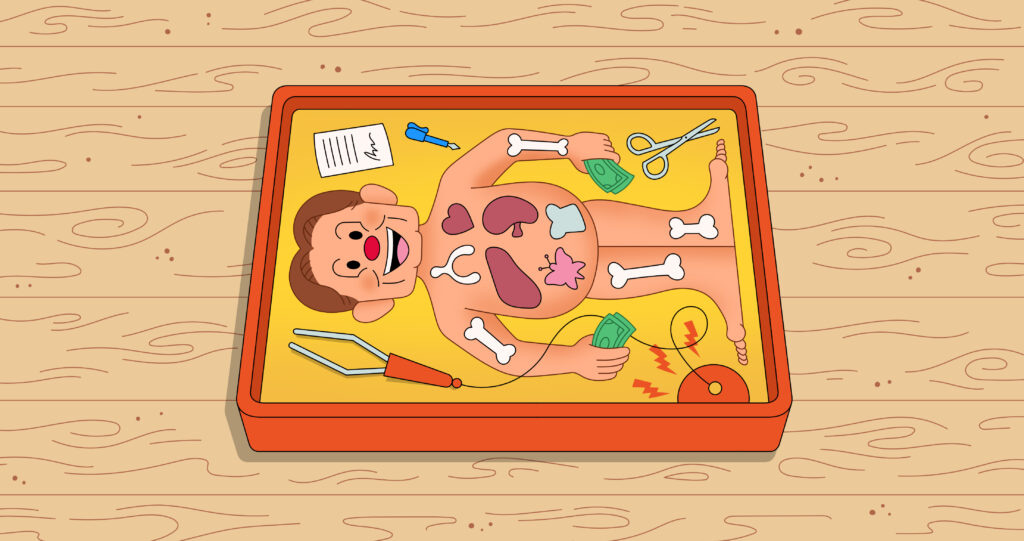

Too few people donate their organs, dead or alive. How can we make it easier?

Duncan McClements and Jason Hausenloy write about encouraging organ donations for Issue 14. Read it online here.

Too few people donate their organs, dead or alive. How can we make it easier to donate, but avoid the abuses that some fear from cash payments?

A hundred thousand people are waiting for an organ transplant in the US. Fifty-eight thousand are waiting for one in Europe. Many hundreds of thousands more people are waiting around the world. To say their experience waiting is unpleasant would be an understatement. Three-quarters of those on the waiting list are waiting for a kidney, and most of them are on dialysis – hooked up to a machine to filter waste products in blood for many hours a week with a myriad of side effects. This is painful, expensive, and risky. Thirty-seven percent of American dialysis patients who previously held a job lose or leave it. Perhaps half will die within five years if they don’t receive a new kidney. Over a third of dialysis patients suffer from depression. And this is the best technology humanity has to treat people waiting for a kidney transplant.

For most other organs, the story is even worse. Up to 12 percent of patients on the waiting list for a liver transplant die every year. Patients on the waiting list for a heart transplant often require an artificial heart to stay alive. Despite its name, this is a device that consists of a metal patchwork of pumps to assist the heart, not replace it. Close to 20 percent of patients given an artificial heart die in the first year, and those that survive have an elevated risk of infection, blood clots, and anemia.

Over 6,000 people on the organ transplant waiting list in the US die every year. Liver disease and kidney disease are the ninth and tenth leading causes of death in the US respectively. We don’t know how many people die globally. Some estimates place the mortality figures in the US from the kidney shortage alone at 43,000 each year, seven times higher than reported figures. This is because many patients who could benefit from an organ transplant don’t make it onto the waiting list at all. Other patients are removed from the waiting list because their condition has deteriorated so much that they would no longer benefit from receiving an organ.

The main medical challenge is not the transplant procedure but getting enough organs. Organs come from two sources: living donors and cadavers – that is, from donations made after the donor’s death. Living donors can only provide one kidney or a part of their liver. Cadavers can theoretically provide all their donatable organs upon death; however, this requires that the donor dies in a certain manner, such as a car crash, and is relatively young and healthy. Only 0.3 percent of cadavers, or approximately 10,000 per year, would be able to donate organs in the US today.

Despite only this third of a percent being eligible, more than twice as many organs come from cadaveric donations than live donors today. Hearts, lungs, pancreases, stomachs, and intestines can only be donated from cadavers. About two thirds of kidneys and over 90 percent of livers come from cadaveric donors.

For both live and cadaveric organ donation, we rely on donor altruism, often at a personal or financial cost to the donor themselves. We need a better way to increase the rate of organ donation. Why don’t we incentivize it?

You can read the rest of the piece here.