Fixing retail with land value capture

How to create beautiful shopping streets everywhere

Don’t miss Issue 15, which we released just over two weeks ago.

Notes on Progress are pieces that are a bit too short to run on Works in Progress. In this piece, Ben Southwood and Phil Levin come up with ways to get more of the bits we love most about cities.

A lot of what we find interesting about cities is the retail within them. We lean on retail – shops, cafes, restaurants and so on – to make cities what they are. Urban economist Ed Glaeser called this the rise of the consumer city, showing how consumption agglomeration was becoming increasingly important, as well as production agglomeration, in driving up urban rents.

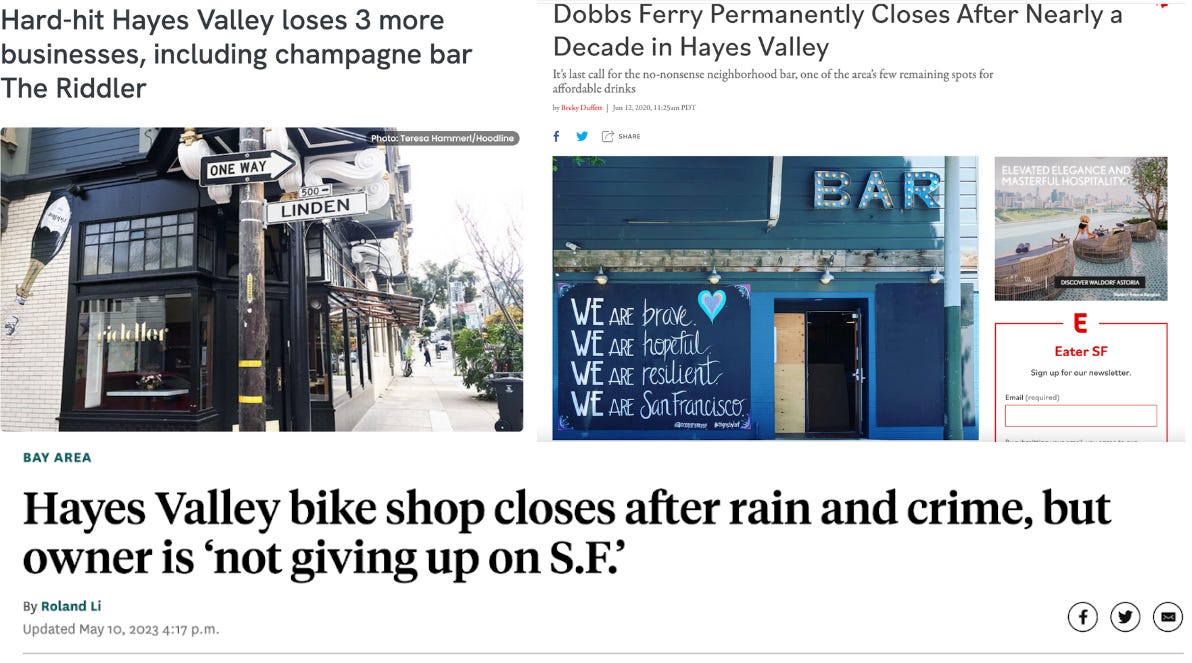

When people say Hayes Valley in San Francisco or Williamsburg in Brooklyn are interesting neighborhoods, what they often mean is that they have interesting retail. Hayes St is Hayes St because of stores and restaurants - rather than something inherent about the streetscape. Williamsburg is Williamsburg because of its wine bars, taco trucks, and fancy coffee shops.

Yet the retail operating environment is as hard as it’s ever been. eCommerce continues to capture share, remote work reduces foot traffic, and crime eats into already-small margins. Almost half of stores shuttered within 4 years in one San Francisco shopping district.

We risk losing something that makes cities what they are, because we don’t have a good model for letting retail capture the value it creates.

Retail suffers from leaky value capture

Hayes Valley has some of the most interesting retail in San Francisco – clothes shops like Marine Layer, Lisa Says Gah and Faherty; some of SF’s best coffee at Ritual; the best bagels in the city at Wise Sons; and some of its best ice cream at Salt + Straw. But the shops there go in and out of business all the time. They barely survive. The neighborhood thrives, the rents go up, the stores struggle.

This is because a big fraction of the value created by these retailers is not captured by them. Consider how you enjoy going into interesting shops – often independent, or quirky, from which you are unlikely to buy something. Going there is a leisure value in itself. Compare to a Walmart where the value is largely in getting food and household items that directly benefit you, and people rarely walk around the shop without buying things.

When an interesting new store, cafe, bar, or restaurant opens up, as well as it profiting from selling its products (if it does), others benefit too: owners of other commercial properties on the street benefit because potential customers are attracted to the area, and owners of homes nearby benefit because their house is now near a nice thing to do. This means that the value of commercial and residential properties go up. A substantial part of the efforts of the retailers on Hayes Street gets realized through the home values of the folks owning Victorians on Fell Street two blocks away.

In American cities, there is an issue with value capture. One party creates the value (in this case retailers), another party (landowners or homeowners) captures it. Of course retailers would love to capture more value. But homeowners would likely be willing to share value too: the homeowners like having the retailers there, yet those retailers often go out of business, making the homeowners worse off. They’d be better off if there was an institution to support them, but it doesn’t exist.

You see a similar dynamic with public transportation infrastructure. The government spent billions building Caltrain’s regional rail service to the Bay Area Peninsula. Unfortunately, most of those stations are surrounded by low density housing. The few hundred homes within walking distance of a station capture a large amount of the value from the infrastructure. Meanwhile, the train system runs unprofitably and needs to be propped up by taxpayers across the whole region.

If you like having shops, parks and trains in your city, the fact that these institutions are failing to capture so much of the value they create should alarm you. The less they capture, the less of it will be created in the first place. As a result, we will have empty storefronts, fewer parks, and less public transit.

Thankfully, history and international practice show us quite a few examples of doing this much better.

Model #1: Internal cross-subsidization (within big developments)

The first model, which has been widely used historically, is unified ownership. When ownership of a main street is splintered, a large spillover from ‘cool retail’ leaks away to unaffiliated parties.

The failure of splintered pedestrian main streets in the 1960s and 1970s led to the rise of destination shopping malls and strip malls. Both make use of ‘anchor stores’ to bring in customers, plus regulated signage, and usually pick a diverse set of interesting shops. A single entity can capture the resulting spillover (cross-subsidize appropriately to maximize value). The single owners captured enough of the benefit from policing them with private security, and from excluding cars, that they could survive where the splintered outdoor main streets could not.

Supermarkets and department stores are classic anchor tenants. They make lower profits, and are often charged lower rents, but bring in customers that benefit all the other shops. Effectively they raise land values. Single ownership allows them to capture some of the land value appreciation, usually by being charged lower rents from the unified owner.

But shopping malls only go so far, mostly capturing only the spillover benefits between businesses, and not the spillovers that all the businesses taken together give the rest of the community (e.g. the homeowners who live nearby).

Developers are beginning to try this, returning to a historic model by having a single entity own both housing and retail, in order to sell the housing for more. One of the authors of this piece helped start Culdesac, where we selected commercial tenants not only on the rents we anticipated the tenant would pay, but also the value they would provide to residents in the surrounding apartment units. For developers building at a sufficient scale, and where zoning permits it (a big if in the USA, where zoning has historically favored separated uses), this approach is fairly common around the world.

This requires single entities that control a large swath of land. It’s part of the reason why large planned communities such as Seaside and Celebration in Florida are able to have nice common amenities. They are in a position to do this cross-subsidization. It’s also why shopping malls from the past few decades as far apart as Bay Street Emeryville in the East Bay or Coal Drops Yard in Kings Cross, London increasingly have housing included.

Transit is another classic example where unified ownership can capture spillover effects.

The Hong Kong Mass Transit Railway buys up the land around new station sites before they start building them. This rail-plus-property model makes them one of the few profitable transit services in the world. Japan goes even further: Tokyo’s metros, trams, and buses are private, and fund their investment into infrastructure by speculating on property they expect to rise in value as a result of their investment.

How could we get cities without unified ownership blocks to create them?

One way to encourage this comes from Donald Shoup: graduated density zoning. This gives properties the right to build more on their plots if they are part of a larger assembled plot. This is effectively how the old light plane–based zoning of 1916-1961 New York City worked as well. The larger the plot, the more externalities internalized. A still further way to enable consolidation might be to give local governments more power to plan for it it where they think it will maximize value for the public, for example by letting them waive transfer taxes (like the UK’s stamp duty), in exchange for a bigger property tax (or in the UK, business rates) take.

Model #2: Hyperlocal taxes, hyperlocal authorities

Local taxing authorities can tax the increase in the land value and funnel it back into supporting retail or common infrastructure. Something like this is happening when local authorities in the UK refuse to let commercial landlords convert their commercial properties into residential ones. They argue that, although it is a benefit considered on its own terms (because it uses the land for something more in demand), it deprives the area of valuable amenities.

But typical local governments are often too big to do this well, in a way that really does achieve the optimal use of the land. Individual local government units – like cities or counties in the US – often have hundreds of thousands of residents, spread over hundreds of square miles. It is very difficult to track where land value is coming from, and where it should be funneled back, and residents thus have no faith that this is what will happen.

By contrast, this sort of value capture can work when the taxing authority is very local. Two thirds of new American homes are in some sort of community association, typically homeowners’ associations, but also co-ops, and condominium associations, and 30 percent of American homes overall are. Buyers opt into these associations, pay annual fees in the thousands of dollars, and suffer their annoying restrictions and demands because they create amenities: quiet, cleanliness/tidiness, safety, or things like public pools and parks. But so far, the community association model has been applied almost exclusively to purely residential areas.

Business Improvement Districts are one way of trying to bring this sort of institution to a high street. Businesses opt into charging themselves higher taxes or fees to support projects that make local businesses more successful like planting trees, improving streets, and tackling local crime or antisocial behavior. But while these districts can help internalize externalities that spill over among businesses, they haven’t so far been applied to capture value that spills over to nearby residents. Given that there is more residential real estate than commercial, a BID that could capture the residential interest too could be an interesting avenue for capturing value and funding public goods.

Special Purpose Bonds (such as this example from New Zealand) are a variation where voters approved bond-funded investments, usually infrastructure, that will be paid back through their property taxes. We can imagine an example where voters are approving not a bridge, but a neighborhood organization that raised a small tax to keep the most interesting shops in business, the streets clean, and the plants fed.

Really bringing this system alive would require creating an institution, like special purpose bonds, or a mixed homeowners’ association-business improvement district that would allow hyperlocal taxes to part-subsidize valued community retail assets.

Selling Stuff → Providing the commons

We are asking a lot of retail in cities.

We want it to be entertainment, a gathering spot or third space, and we want it to help form a city’s culture. We also want it to pay its rent. Delivering on all of those goals may be too much to ask of our retail base, without some help.

We offer a prediction: As the ‘selling stuff’ model of retail becomes less viable due to internet-based alternatives, the ‘commons / third space’ version of it may rise up instead. There are already examples: The Commons in San Francisco took over a former clothing shop and runs a member-based ‘home outside of home’. These models can work for private spaces, but they won’t fully captured spillovers.

These value capture models could help neighborhoods more directly provide the thing people actually want without having a shoehorn a high-margin retail business model alongside it. And they may provide a path to capturing, in a more direct way, the benefits a space gives to its surrounding community.

Ben Southwood is co-founder and managing editor of Works in Progress. Phil Levin is founder of Live Near Friends and a founding member of Culdesac.