Notes on Progress: Agglomeration benefits are here to stay

Building more homes in the most productive cities could massively boost productivity

A recent study by some top economists suggests that wage differences between cities are primarily driven by skill differences. Some commentators have used this to argue that there would only be small gains from allowing many more homes to be built in the most productive cities, because people are already being paid mostly based on their skill, not their location.

But this story is mistaken, for a few key reasons. First, the paper in question does find very substantial benefits to location, enough that Americans could be thousands of dollars richer if moving around was less expensive. Second, the model used to interpret the data has two implications that don’t fit the real world: that rent variations between cities are only driven by differing amenities, and that there is no gap between house prices and the cost of building more housing. Both of these are false.

There are also more subtle problems with the paper. Low skilled workers do not move or sort much between cities because of the effective movement barriers – housing costs – documented in the paper. Their wages vary substantially between cities but since they do not sort, the benefits they would see if they moved may not be fully taken into account.

Similarly, we can reasonably predict from international and historical evidence that without such housing restrictions, some cities would be much larger. These agglomerations have not been allowed to exist, and their potential effects cannot be observed in the data – such effects are de facto assumed to be zero, which is clearly untrue.

The methodology also effectively assumes that all possible combinations of industry-location and worker exist. But many do not – because in a national market, they would be driven out of business. To observe how much more productive software firms really are in Silicon Valley, we would need pure software clusters to also exist in the cities where they would be least productive.

Barriers to movement and international income differences

Before we look at the paper, though, let’s look more broadly. Why do people earn such different wages per hour across different countries, or for that matter, workplaces?

One possibility is that people in America or at a company like Microsoft are just more skilled than people in a corner shop in Britain, or Mexico. To some extent this is surely true: America has the world’s best universities, and many of the best schools, excellent nutrition, and pretty good environmental quality. America’s most productive companies, such as Microsoft, tend to suck in the best and brightest immigrants from around the world.

Another possibility is that American institutions and companies are better. America has a deeply-established rule of law, a well designed tax system, and high social trust. The government subsidises research and development, provides a reasonable safety net, keeps crime low by international standards, and maintains substantial infrastructure. High productivity companies tend to have sophisticated management structures, enough resources to afford nice offices, and processes that ensure there aren’t crises like workers not being paid on time. And America has a very large market, with twice as many people as Mexico, and five times as many as Britain.

How can we tell which effect predominates? One standard method is looking at what happens to wages when a particular individual moves between companies or countries. This method controls for individual differences, like the amount people have invested into skills. For example, the lowest-paid Nigerians in formal work get around $70 per month. By contrast ninety percent of American workers earn more than $560 per week. Assuming a Nigerian worker at the lower end of the skill distribution could do a job at the low end of the American skill distribution, this implies most of the difference between these countries is not due to differences in individuals’ skills.

Experimental results in the economic literature find a similar thing. At times, there has been a lottery in New Zealand to select which Tongans are allowed to migrate there. New Zealand today has a GDP per capita around ten times Tonga’s; at the time of this 2010 paper it was just over five times Tonga’s. Tongans who were randomly selected to be allowed into New Zealand saw their incomes go up around 250%, implying at least half of the national income gap was not due to differences in individuals’ skills (though they did have higher incomes than average beforehand, implying the existence of selection effects where more skilled people tend to migrate). A range of other similar experiments and studies find similar effects: nearly everyone can earn more if they move to a higher earning country.

If there were no immigration restrictions, then we would generally expect people to move to where their talents were most valuable, though there are countervailing pressures: they may like the new culture less, and miss their family and community. In surveys, nearly a billion people say they’d like to move to the USA. In practice, few can satisfy the requirements, invest the time, and spend the money necessary, with the highest skilled most capable of overcoming those hurdles. The result is more sorting of the highly skilled to rich countries like the USA, with those less skilled remaining in their country of birth.

The cost of housing and intranational income differences

Now look within the America that exists today. There are no legal immigration restrictions between cities. But there are other things that constrain movement, such as housing costs: rents and house prices. If housing costs are higher in one place than another, then even if wages and productivity are also higher, it may not make sense for an individual to move.

Consider ‘Why Has Regional Income Convergence in the U.S. Declined?’ by Peter Ganong and Daniel Shoag (which I wrote about on my personal substack). They find that US states used to converge towards a similar steady state income because people, especially the worse-off, used to move from lower- to higher-income states. However, this was when housing was abundant, and cost about as much to rent or buy as it did to build. Now people move less, because housing prices and rents are well above the cost of building housing.

The mechanism we propose for explaining the decline in income convergence can be understood through an example. Through most of the twentieth century, both janitors and lawyers earned considerably more in the tri-state New York area (NY, NJ, CT) than their colleagues in the Deep South (AL, AR, GA, MS, SC). This was true in both nominal terms, and after adjusting for differences in housing prices. Migration responded to these differences, and this labor reallocation reduced income gaps over time.

Today, though nominal premiums to being in the New York area are large for these two occupations, the high costs of housing in the New York area have changed this calculus. Lawyers continue to earn much more in the New York area in both nominal terms and net of housing costs, but janitors now earn less in the New York area after subtracting housing costs than they do in the Deep South.

This sharp difference arises in part because for lawyers in the New York area, housing costs are equal to 21% of their income, while housing costs are equal to 52% of income for New York area janitors. While it may still be worth it for lawyers to move to New York, high housing prices offset the nominal wage gains for janitors.

This sounds an awful lot like the immigration story, with housing shortages playing the role of immigration restrictions – though of course the gaps are much smaller, because Alabama is still a whole lot richer than Nigeria.

Card, Rothstein, and Yi: the findings

But Card, Rothstein, and Yi appears to contradict this story. The authors use US government data with linked wages and industry information for individual workers across time. For example, the data entry for me would include ‘2022, Technology; 2021, Think tanks’, and so on through the years in the data. Astonishingly, they have data covering some 95% of the private firm employees in the USA from 2010 to 2018.

Since they can see how my wages change as I move across industries and places, they can estimate how much these industries change my income relative either to other industries or the same industry somewhere else. Each worker will have a trajectory over the years going through different industries in different cities. Since we have practically every worker in the economy, there will be thousands of cases where many different workers work for the same industries in the same cities. Their model uses these coincidences to attempt to estimate each worker’s productive potential (Card et al. use the term ‘earnings capacity’). Then on the flipside there will be thousands of cases where the same worker works at different industries in the same, or in different cities, over time. By comparing their productivity at these different industries in the same city, or in the same industry in different cities, we can work out the effect on productivity of the city and of the industry.

Card and colleagues find that employees enjoy significant improvements in their wages when they move to more productive industries and/or more productive cities. But while they do find that people earn more when working for the highest productivity industries and living in the highest productivity cities, these two factors together only seem to account for half as much wage variation as the wage variation driven by the skills of the employee in question. The key factor in why those industries/places have higher incomes for their workers is that those workers would get high wages wherever they went. Skill is the dominant factor.

The implications of Card

Some commentators have used the authors’ findings to say that there are only small economic benefits from people clustering together, in turn implying that there are minimal wage benefits to moving city, and thus that liberalising housing supply in the fastest growing and richest cities could not appreciably affect productivity. In the paper, Card and team agree that if they had found a pure skill sorting story, then it would imply that moving city has no effect on earnings, and that policy moves that make moving easier, like making housing more abundant in the most in-demand cities, would have small effects.

The problem with taking this inference from their paper – that there would be minimal productivity benefits from making it easier for people to move around the country to find better jobs – is that even within their paper some third of the variation of income between cities is driven by industry and location themselves. One third is not a trivial amount. It’s certainly true that the impact of pure city size is low in their model as compared to previous research which failed to control for worker skill as thoroughly. But it was always obvious that the clustering that drove the most productive cities was more down to quality than quantity – which is why Boston is richer than Bogota. Their paper cannot really be deployed in favour of the case against the wage benefits to moving to a different city, since it manifestly shows substantial effects of doing so. City and industry just aren't as important in determining wages, within the USA, as individual skills.

Consider how strange the full ‘skill story’ would be. It would say that the reason why McDonald's crew members are paid $15 in New York City and under $10 in Alabama is because NYC crew members are just much more competent than those in AL. I’m sure that dealing with overwhelming hordes of city customers does, to some extent, train them up, but it seems rather more likely that branches of McDonald's in dense areas with more customers are just more productive per unit of land, labour, and capital. And Card et al observe huge nominal wage differentials just like this for all sorts of lower-skilled jobs like McDonalds staff!

Why Card, Rothstein, and Yi don’t disprove agglomeration benefits

This debate matters because a range of other evidence suggests that regional inequality, slow productivity growth, and various other problems are substantially driven by constraints put on internal migration – expensive housing in destination cities. As mentioned above, the results of Card's paper have been taken by some to mean that this is untrue, and that movement would actually not raise anyone’s wages much. Implicitly, these people are saying, janitors in New York City and San Francisco are earning their higher wages by being harder-working, more motivated, and possibly smarter janitors – in many cases they may be immigrants who did higher skilled but worse paid jobs back home.

The debate is basically about a thing called agglomeration benefits. Agglomeration benefits are the benefits to collaboration that people get when they are close to one another. On a small scale, they are the benefits to productivity that members of one company enjoy when they are all in the office together. On a larger scale they are the benefits that people get when they all live in the same city and have a huge pool of people to buy from, sell to, and work with. According to one interpretation, the Card findings show that countries like America have got as much as they can from these benefits, and they can’t be exploited to make further income gains. I think this interpretation is mistaken, for the five reasons I mentioned in the introduction. The first two relate to the interpretation of the paper; the last three relate to the paper itself.

The first relates to the costs for employers to move city, and the collective action problems in doing so. One assumption that underlies the ‘anti-agglomeration’ interpretation of the Card findings is that employers – companies – will move to where they can buy a given amount of labour productivity the most cheaply. Firms will not stay in a given city just because. They are there because they can get the most bang for their buck there, in terms of employment. This is clearly broadly true. But the Card team take this to show that each industry already has the optimal current set of employees (given the underlying level of amenities in each city) – else the employer would move city. This would amount to assuming away agglomeration benefits!

It’s certainly true in history that some firms have done just this: manufacturers created their own ‘company towns’ so they could minimise other costs and get as much productivity for the wages they pay as possible, and they’d try to locate these where labour was cheapest. This works when you don’t depend on a whole ecosystem outside of your control for your success. But for something like a New York City advertising firm, there is little choice. The workers are there, the clients are there, the investors are there. They can’t unilaterally decide to move without losing out on all of those benefits, and it would be difficult for all the industries in New York to simultaneously agree to relocate to somewhere with unlimited housing supply. Thus, while you may in fact be getting the most bang for your buck in New York City, this is not necessarily because there are not equally appropriate people elsewhere to do the job, but possibly just because you are dependent on a broader ecosystem you cannot shift on your own.

Cities are a sort of Schelling Point. It is hard for any one firm or individual to shift the location of economic activity. We see this in the real world in history: one study found that French cities persisted in Roman locations for thousands of years, even after the pattern was inefficient as it gave them poorer access to navigable waterways than, say, Britain. And that was despite the absence of housing restrictions!

The second issue lies with the way housing costs and amenities vary between cities. Card et al. observe in their data that ‘real’ wages, i.e. wages after taking account of rents or house prices, are actually lower in their superstar cities, even though wages are higher. They suggest that any gaps in rents they observe between cities are driven by some cities being nicer to live in than others – e.g. they have nicer weather, better restaurants, and so on, to explain this otherwise puzzling result. However, they do not observe this quality gap – that pricier cities are nicer to live in – in their data.

This adds a further complication to how we should interpret the paper’s findings. In a competitive market, the price of something is driven by the cost of producing another one of that thing (plus a small profit margin). If it were nicer to live in one city than another, we would expect more and more housing to be built there, to enable lots of people to move there, until it became more and more expensive to build more homes. People would dig out basements, build high rise, and build on gardens, farmland, and parks, until it was no longer worth it to buy the expensive housing to get the nicer city.

By and large, this increase in housebuilding costs, which would fit the ‘higher rents means nicer city’ story, is not what we see. For example, there are many amenities to living in the Dallas-Fort Worth commuter zone, or the Atlanta commuter zone, or indeed the Houston commuter zone – although perhaps to my tastes fewer than living in New York City. But these cities have abundant housing by big city standards, with minimal gaps between the cost of constructing housing and the cost of buying or occupying it. Though costs are higher in superstar cities, the majority of the gap is down to a larger wedge between costs and prices, which indicates that the gap is down to zoning or planning restrictions – a pure scarcity of housing.

If this is true, then how else could we make amenities vary so perfectly with rents/house prices? One way is assuming that the supply of housing is fixed. Another is assuming that regulatory constraints on housing, though they exist, are equal between cities. In both of these scenarios, property becomes more expensive in nicer cities because the people with higher skills and productivity bid it up, then firms site there so they can employ the more skilled workers. Both scenarios are clearly untrue: America builds hundreds of thousands of homes every year, and regulatory restrictions vary widely.

If in fact the bulk of the gap is down to housing scarcity, not city amenities, and if the differences in income between cities can be largely down to higher productivity without that implying that moving doesn’t raise productivity, then this makes the agglomeration story look much more convincing and simple. Some cities just have higher productivity, most likely because of the people who are already there. To move all of these people at the same time, we would have to perform extraordinary feats of coordination, so they tend to persist.

Under-observing agglomeration

In fact, as suggested above, we can take most of Card et al’s model seriously and still think that we could generate large income and welfare gains by enabling people to move city (e.g. by relaxing limits on building housing in high-wage cities). But there are some additional problems with extrapolating too widely from the findings.

First, the data doesn’t show much movement or sorting of lower skilled workers, for the same reason why the Alabamian janitor moved to New York City in the 1960s and doesn’t today. And yet, lower-skilled workers also benefit from moving to the highest productivity cities. In fact, the proportionate increase in their wages due to moving may in some cases be greater than for higher income workers. Recall how McDonalds pays around $15 per hour in New York City and under $10 per hour in Alabama. What’s more, moves by lower skilled workers may also increase the productivity of higher skilled workers by lowering the cost of outsourcing, for example by working as assistants, maintenance workers, and in childcare.

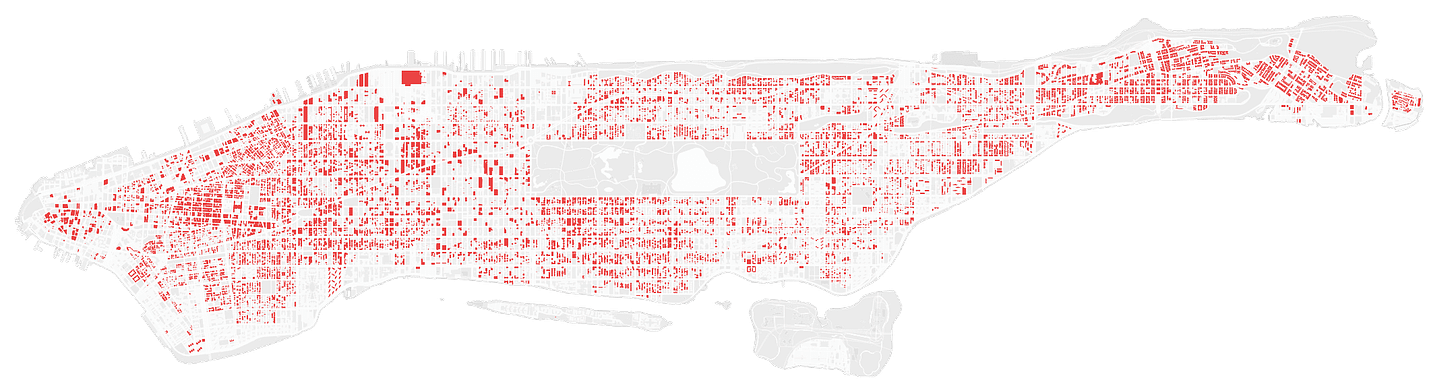

Second, this intuition applies for higher skilled workers too. Stringent housing restrictions are preventing really large agglomerations from emerging at all in the USA. According to the two famous studies – Hsieh & Moretti and Duranton & Puga – New York City would grow by tens of millions of people if allowed to,continuing the breakneck growth seen from 1800 to the mid twentieth century. If this is true, then small observed agglomeration benefits may just be an outcome of our system, which isn’t allowing any of the most productive possible agglomerations to evolve.

Third, the observed differences between cities may be understated due to selection effects. Goods and services are more mobile than workers. Housing restrictions make it unattractively expensive to move across cities in the USA, but the trade in goods and services across the country makes it quite easy for consumers or companies to switch the companies consumers or firms choose to buy from. This creates a selection effect that drives firms in a particular industry out of business if they are in cities where that industry is less productive.

For example, pure software firms in a small city like Omaha will tend to be driven out of business due to competition with high productivity firms in San Francisco. This will be prevented only in idiosyncratic cases, such as if Omaha had a need for a specific type of software that could be better coordinated with local programmers. As a result, comparing productivity across cities on a per-industry basis will tend to understate the productivity differences between cities. Where the difference is the greatest disadvantage, many of those firms will already have gone bust. That means the differences between cities will look smaller by comparison with the variation in skills of the workers.

In other words, the Card et al analysis of the current outcome will tend to obscure the benefits of agglomeration, since the hypothetical less productive industry-location pairs are eliminated by national competition.

Due to these three considerations – low movement of low-skilled workers, city growth being blocked, and hypothetical low productivity firms being driven out of business and hence not observed – Card underestimates the power of agglomeration benefits.

Conclusion

This, I believe, is the misunderstanding that readers of Card, Rothstein, and Yi have fallen into. It’s still clear that housing issues are substantially holding down productivity, by perhaps 10% in the USA, and maybe as much as 25% in the UK. That leads to lower wages and incomes, and a poorer world for everyone. And thus it’s still clear that there is a huge prize to coming up with a politically acceptable zoning system that permits more homes in the key locations.