A review of Charles Piller’s Doctored

How fraud and bad research derailed years of Alzheimer's progress

Notes on Progress are irregular pieces that appear only on our Substack. In this piece, Tom Chivers reviews Charles Piller's Doctored, which explains how fraud derailed Alzheimer's research for decades.

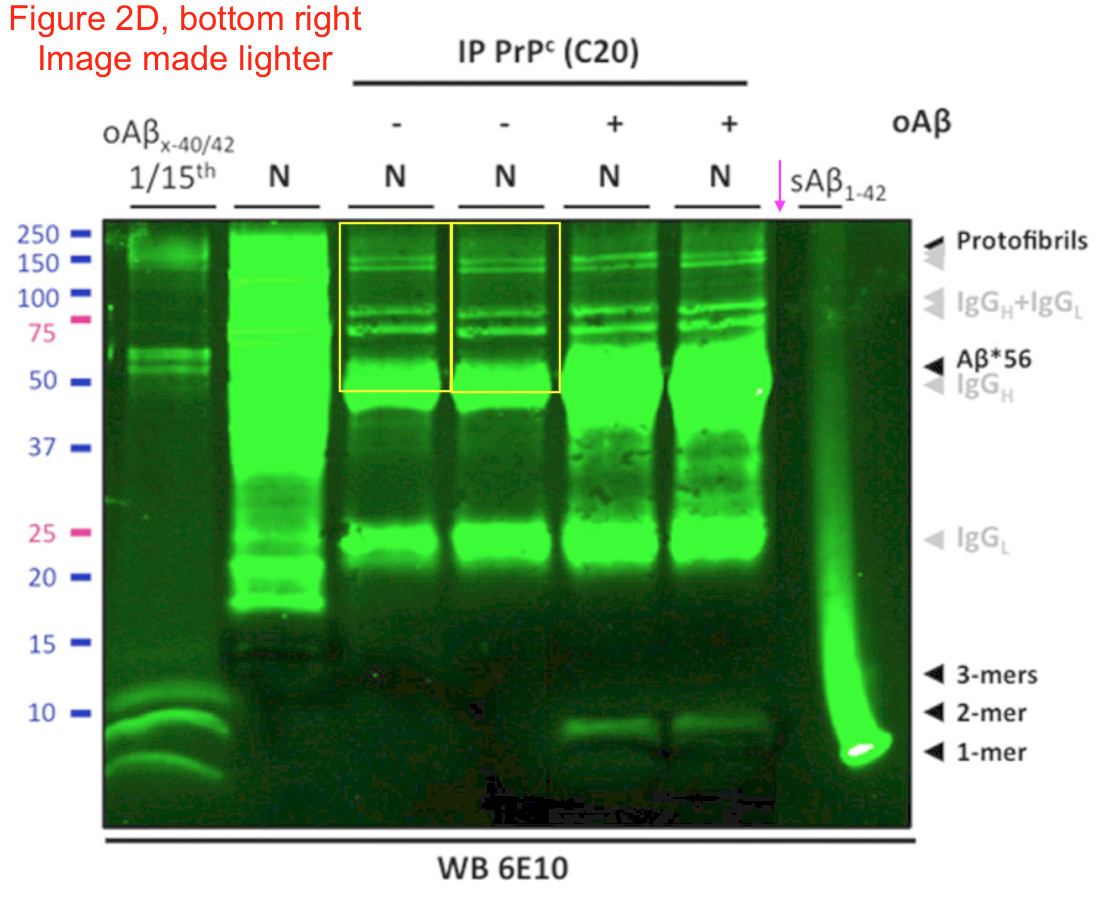

In 2006, an apparent breakthrough was found in the fight against Alzheimer’s disease. A protein, awkwardly named 'amyloid beta star 56' or Aβ*56, when injected into rats, apparently caused memory loss and other symptoms of dementia. Its discoverer was Sylvain Lesné, a young scientist at the University of Minnesota. His boss, the neuroscientist Karen Ashe, touted the discovery as 'the first substance ever identified in brain tissue in Alzheimer’s research that has been shown to cause memory impairment', and the excitement was enormous: Nature called it 'a star suspect.' The original paper, also in Nature, has since been cited 2,300 times.

There is a problem, however. Aβ*56 may not exist.

Dementia is a huge killer. The World Health Organisation estimates it kills 1.8 million people a year, and lists it as the seventh biggest cause of death. But while efforts to treat other illnesses – infectious disease, heart disease, cancer – have made progress in recent decades, the same is not true of Alzheimer’s. 'Between 1999 and 2015, rates for the top three causes of death in the United States fell sharply,' writes Charles Piller in his new book Doctored. 'Alzheimer’s rates and fatalities went in the opposite direction.'

Piller, an investigative journalist and a beneficiary of nominative determinism, was instrumental in uncovering part of why that is, in an article in Science in 2022.

Lesné, who published many more papers on Aβ*56, was almost the only researcher ever to detect the substance: Only a handful of other groups have published anything on it, and other researchers have tried and failed to find it. Certainly, no other group has found any indication that it affects memory.

And 20 of Lesné’s papers, it would turn out, thanks to dogged detective work by other scientists, contained fabricated results, in the form of doctored images. The original Nature paper, along with several others, has now been retracted. Efforts to chase this phantom have cost millions of dollars of public money, and given false hope to Alzheimer’s patients and their families – but most crucially, they helped send Alzheimer’s research down a false path.

Amazingly, this wasn’t even the only time that has happened in Alzheimer’s research. The drug simufilam, when it was first developed in the 2000s, was originally intended to be a pain-relief drug. That didn’t work, but its creator Cassava Sciences soon found another use: apparently, it helped detangle misfolded proteins in the brain, potentially preventing or curing Alzheimer’s. Once again, the findings – in frozen-but-revivified brain tissue – all came from a single researcher, City University of New York neuroscientist Hoau-Yan Wang, whom Piller describes, archly, as having 'magic hands' – that is, 'a preternatural talent to achieve hoped-for, problem-free results, time after time, experiment after experiment.'

Once again, it appears to have been based on doctored images, and Wang has since been found by his university to have engaged in 'egregious misconduct.'

Alzheimer’s research has for decades focused on the 'amyloid hypothesis' – that certain misfolded proteins build up in the brain and cause dementia. Both the Aβ*56 research and simufilam grew out of that hypothesis and, with their apparent success, reinforced it.

As Piller points out, though, despite that focus, the hypothesis has led to little in the way of meaningful treatments. In 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the use of the pharma company Biogen’s drug aducanumab, which reduced the levels of amyloid plaques in brains. It was said to be the first drug to slow the progress of Alzheimer’s.

But aducanumab, trademarked as Aduhelm, had two subtle flaws: Biogen’s own trial was stopped early because it showed no benefit and because 41 percent of patients suffered brain bleeding or swelling. That’s called a 'termination for futility'.

So how did it get approved? Well: Biogen reanalysed the data looking at a subset of participants, found a slight improvement compared to placebo, and asked the FDA to approve the drug on the strength of it. The FDA appointed a panel of experts to assess it: 10 out of the 11 voted against approval and one was uncertain. But the FDA approved it anyway, a shocking decision that led to three FDA advisors resigning.

Aducanumab’s story is shocking, and the treatments that followed it to FDA approval, lecanemab and donanemab, are only somewhat better: they both also cause dangerous bleeds in many patients, with some deaths recorded, and both only slow patients’ rate of decline rather than reversing it – and even that is borderline imperceptible, clinically speaking.

As I was reading Piller’s book, incidentally, after years of accusations of fraud and malpractice, Cassava Sciences announced the results of a major trial into simufilam. To the surprise of nobody who had paid attention, the results were null: 'Volunteers who took the drug performed no better in cognitive or everyday-life activities than those who received a placebo,' Piller wrote in Science, and the drug had no impact on biomarkers of Alzheimer’s either.

As Piller tells it in Doctored, the amyloid hypothesis has dominated research. Some researchers talk darkly of an 'amyloid cabal' that chokes off possible alternative avenues. And the discovery of (what looks very much like) fraud in some of the most high-profile areas of amyloid research could understandably make people lose confidence in the whole idea.

Maybe that would be justified. Reading Piller’s book, though, I wanted to tell another story as well – one which Piller himself mentions, but understandably, since he has done so much work uncovering the fraud, does not make his main focus.

Since 2011 much of science, notably the social sciences, has been rocked by the 'replication crisis', something Works in Progress has addressed before. The statistical methods used in science turned out to be churning out a lot of false positives: slicing up data in arbitrary ways, or using small sample sizes or poor measurement tools that are vulnerable to noise, in particular. And the incentive structures were off: journals would be more willing to publish positive results, so negative results tended to sit unseen in file drawers, skewing later reviews of the literature; and scientists’ careers progressed according to how many papers they published, so they would chase those positive results, sometimes by putting their thumb on the statistical scales.

None of that required 'fraud' per se, although it was and remains far from unheard of. You can get a lot of exciting-looking results without making up data if you just take real but noisy numbers and keep chopping them up until they say what you want.

That is the story that Alzheimer’s research makes me think of. The fraud is shocking and scandalous. It really is – I am not in any way downplaying that; the idea of falsifying images and results, giving terrified, dying patients and their families false hope, and sending research down useless paths for years, is morally outrageous.

But in a way, the fact that the not-fraudulent stuff is less shocking is itself a disaster. One of the early studies that Cassava used to tout simufilam’s potential – which it claimed showed actual improvement, not merely a slowing of decline – had 50 participants and no control group and should have been ignored. Both Cassava and Biogen re-analysed data after finding null results and came back with suddenly exciting findings.

And, as Piller notes, negative results often went unpublished, because journals and pharma companies are often not interested in them. Many unsuccessful efforts by other labs to discover Aβ*56 never saw the light of day, because boring we-didn’t-find-anything studies are not as exciting as 'maybe we’ve solved Alzheimer’s!' – but if they had been published, then perhaps the apparently fabricated results would have been detected sooner, and scientists would have moved onto more promising avenues. Researchers wouldn’t have spent 16 years chasing a protein that may not even exist.

I’ve written a lot about the replication crisis in the past, and it’s usually in the context of social sciences. It matters: it’s important if, say, the education system wastes money and time trying to instill a 'growth mindset' in children – an idea that hasn’t replicated – or people convince themselves that 'power posing' will make them confident. But it won’t, in a direct sense, kill anyone.

The sorry state of Alzheimer’s research, though, is a reminder that good epistemic practice in science matters much more than just a bunch of psychology professors publishing counterintuitive results that can win them lucrative after-dinner speaking gigs. Getting the stats and incentives wrong can very literally kill people, by pushing research away from useful areas towards useless ones, and derail efforts to solve one of humanity’s biggest and most horrifying killers.